Listen to my interview with Pedro Noguera (transcript):

Sponsored by Peergrade and mysimpleshow

With every passing year, it seems that our collective awareness of educational inequity is growing. I say “collective” with some unease, because for people who belong to marginalized groups and others who have taken the time to educate themselves well on equity issues, the awareness has always been there. Equity work is not a trend; it’s not a new thing.

But the chorus that is raising awareness about equity issues is getting louder, because more voices are speaking on bigger platforms: More books are being published, more podcasts and films are being produced, and new forums, like Val Brown’s incredible Twitter chat, #CleartheAir, are helping to reach more people. I’m hearing more educators talking about issues like systemic racism, school pushout, and the opportunity gap, more educators seeking information about restorative practices, more educators who once upon a time might have assumed they weren’t part of the problem and suddenly realizing that, in fact, we all are.

And awareness is a good first step, but it’s not enough. We need to know what to do with that awareness, what actions we can take to move the needle toward justice.

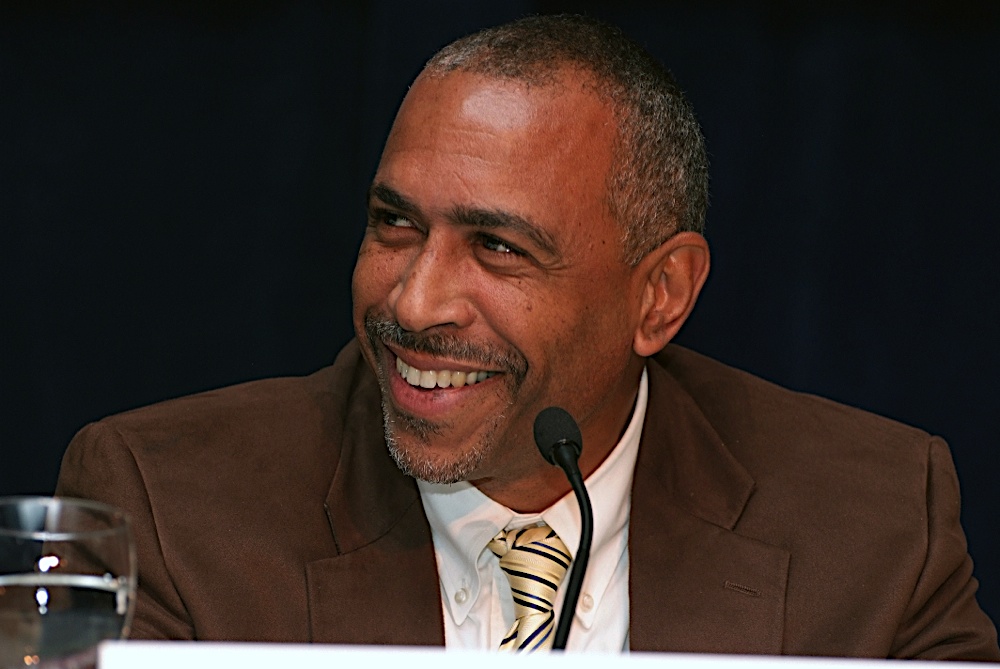

To learn more about that kind of action, I talked with Pedro Noguera, Distinguished Professor of Education at the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies at UCLA. Dr. Noguera has been a leader in educational equity for over two decades, authoring 12 books, publishing over 200 articles, and speaking and consulting with schools and districts all over the country.

Pedro Noguera

Noguera’s most recent project has been the founding of UCLA’s Center for the Transformation of Schools, an organization that describes itself as a “thought partner for schools, districts, and states in fulfilling their mission of ensuring that all children receive the education they deserve.” The Center works toward equity in academic outcomes in three ways: first, by conducting research that identifies the most effective interventions and strategies to support student learning and mitigate the effects of poverty; second, by developing a network of schools and districts engaged in transformative work that can be used as a model for others; and third, by creating stronger bridges between health, education and social services to promote student well-being and wellness.

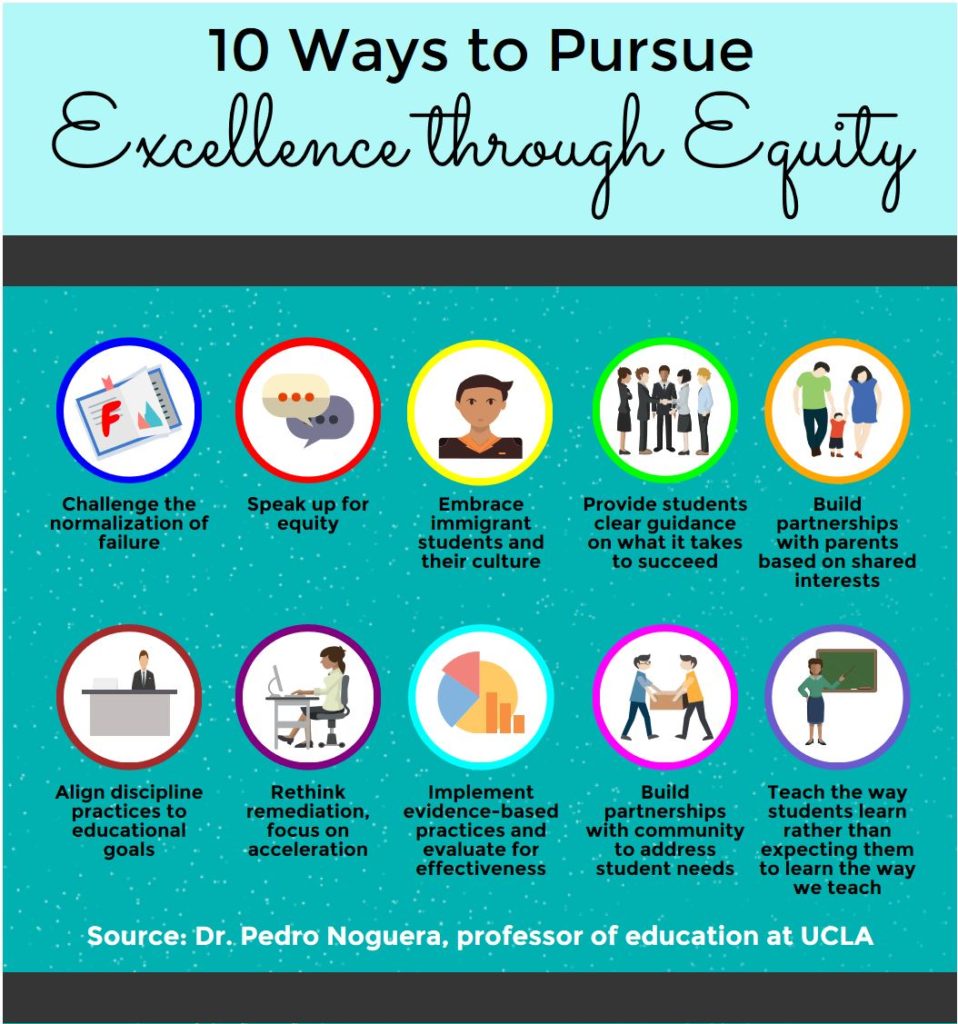

Here, Noguera shares ten specific actions educators can take to pursue excellence through equity. Some of these are things we need to speak up about, some are shifts we need to make in our own mindsets, and others are changes we can implement in our own practices.

1. Challenge the Normalization of Failure

“Whenever you’re in a school that has grown accustomed to the idea that certain kids from certain backgrounds are underperforming, are more likely to be in special ed, or are more likely to be disciplined,” Noguera says, “after a while people simply think it’s normal and nothing can be done about it.”

One way to push against the status quo is to look for positive deviants. “If you have many minority students who are not performing,” Noguera explains, “look at the ones who are performing and find out what’s different about them and their experience, because those outliers will tell you what we need to do more for the other kids.”

2. Speak Up for Equity

“There are lots of ways in which educators can become complicit in the production of the disparities, in the perpetuation of the achievement gap, because we simply haven’t acknowledged that there are ways in which some kids have been denied the opportunity to learn,” Noguera says. When we notice things that are creating inequities in our system—like the least experienced teachers being assigned to the students with the greatest needs—we need to speak up.

This is easier said than done, he admits, because it can mean having uncomfortable conversations, but it’s absolutely necessary for progress to occur.

“If you want to just be nice, you’re not going to make any change. It doesn’t mean that you’re insulting, that you are attacking people; that’s not helpful either. But we do need to be able to engage in honest conversations about what’s occurring for our kids.”

3. Embrace Immigrant Students and Their Culture

Too often, our English learners are being taught in ways that marginalize them, undervalue their unique strengths, and limit their progress in core subjects. Noguera urges educators to push for something better.

“When immigrant students feel included,” he says, “when they are taught by competent staff who are able to teach them not simply ESL classes, but in science, in math, they do quite well. In the same ways we want to mainstream special ed students, we want to make sure all kids have access to the full resources of the school and the curriculum. Immigrant students, whether they’re English learners or not, need to take rigorous courses, need to have access to counselors. We can’t allow language to be a barrier to providing high-quality educational service.”

To see what this looks like in action, Noguera recommends checking out the work of the the Internationals Network of schools. They have developed a model for serving English learners that results in exceptionally high rates of high school graduation and college attendance.

4. Provide Students Clear Guidance on What it Takes to Succeed

“We have to demystify success for kids,” Noguera says. “There are certain strategies that we know are more likely to lead to success, and we need to make sure kids know what those strategies are.”

Explicit teaching of things like study skills, organization, note-taking, and time management can all help students build habits that will lead to success in school. Noguera also points to the resources from AVID, whose programs focus on these skills.

5. Build Partnerships with Parents Based on Shared Interests

“Parents want the same things our schools want: Our schools want kids to be successful, so do the parents,” Noguera says. “Once you acknowledge that, then what you’re after is a partnership where the parents are reinforcing at home that learning is important to success in school. Partnerships have to be based on respect, trust and empathy—not pity, but empathy. Certainly not condescending attitudes toward parents. Patronizing attitudes do not build partnerships.”

“It’s very rare to find a student who’s successful who does not have parental support,” he points out. “Our work has got to be to get more parents involved with their children, and the most important form of parental involvement is not coming to the school to sell cookies, but what they do at home with their children, getting them to bed on time, making sure there’s a place to work, asking about the work, checking in with the teacher so they know what’s going on at school. All of those are things all parents can do.”

6. Align Discipline Practices to Educational Goals

The way we choose to discipline students is a key component of their overall success. “We’re most likely to punish the kids with the greatest needs,” Noguera says. “And how do we punish them? Typically by denying them learning time. We start by referring them to the office. If that doesn’t work, we suspend them. If our educational goal is to keep kids in school, to keep them learning, then we need to make sure that when there are behavior problems, we figure out what’s behind the behavior problem, and then we always work to keep the kids connected to learning.”

“There must be consequences for inappropriate behavior,” he continues, “but the consequence need not involve not learning. We have to be much more creative. Community service can be a consequence, restorative practice is a great strategy when implemented well for addressing the relationships between teachers and kids. We’ve got to figure out ways to make sure that schools are safe and orderly, but also that we’re not using discipline as a way to deny kids learning opportunities.”

7. Rethink Remediation, Focus on Acceleration

“We’ve known for many years that if you label a child slow, you put them in a group with lots of other (kids with that label), you assign a teacher who is not particularly effective to work with those kids, what you’ve done is create a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Noguera says. “That child will be slow, because you’ve set it up that way.”

Instead, we should be focusing our efforts and resources on acceleration, opportunities to help students who are behind to move more quickly through the curriculum—like in summer programs, for example—so they can be caught up for the following school year. One organization that has been successful in this area is MESA, an organization that provides opportunities in math, engineering, and science to students who are often the first in their family to plan to attend college.

8. Implement Evidence-based Practices and Evaluate for Effectiveness

One vital component of ensuring equity for all students is to make sure we’re using the most effective teaching practices in our classrooms.

“There’s a tendency to disconnect equity issues from basically good teaching strategies,” Noguera says. “I think it’s a mistake when we put equity under this kind of rubric of addressing implicit bias; that’s not to say that we don’t need to do that, but if you don’t connect that back to what teachers do on a regular basis to teach their students, then you’re not going to see a change in outcomes, and changing outcomes ultimately is what this is about.”

“Right now we’re living at a time where we have research on how to serve all kinds of kids,” he says. “The real gap that we don’t close is the gap between the research and the practice. The key is to evaluate, to make sure it’s having the impact, but also to work with your local colleges and universities to make sure you’re drawing on strategies and practices that the research shows are effective.”

9. Build Partnerships with Community to Address Student Needs

“We can’t expect schools to do everything,” Noguera says. “We have a large number of homeless children in our country, kids who arrive at school hungry, kids who need eyeglasses and have trouble reading because they can’t see. We need partnerships with hospitals, with health clinics, with nonprofits, with churches, with any community entity or agency that can help us in addressing the needs of our students. We can’t expect the teachers to be the social workers and counselors and to teach. They need help.”

For schools interested in developing these kinds of partnerships, two models to look to are the Children’s Aid Society and the Harlem Children’s Zone, both in New York City.

10. Teach the Way Students Learn Rather than Expecting Them to Learn the Way we Teach

“In many of our schools—and I think this is more likely to be the case in high school and middle school—the assumption is that the kids will learn the way we teach,” Noguera says. “If they can’t, then something’s wrong with the child. (But) in many of our schools, we’re not teaching kids the way they learn. If you go in many classrooms you’ll see kids sitting passively, listening to a person talk.”

That kind of passive learning isn’t the most effective way to get many students to learn. “Class time needs to be work time for kids,” Noguera says. “It’s only when they’re working that a teacher can see who’s getting it, who’s not, who needs more support. We need to move away from a teacher-centered approach and move toward a student-centered approach. Kids learn through experience. Kids learn through mistakes. Kids learn by asking questions, through interaction. If we taught kids the way they actually learn, our classrooms would look very different than they do right now.”

At the end of our conversation, Noguera is quick to point out that every item on this list represents challenging, long-term work.

“I don’t want to make it sound like it’s easy, like following a recipe from a cookbook,” he says. “Every school has a culture, and the cultures often can get in the way of doing some things that make sense.”

What can really move the needle is having clarity about what makes a difference, then following in the steps of schools that have already made progress.

“That’s the good news,” he says. “There are lots of examples of schools that are serving kids well, all kinds. And the existence of those schools is the proof that the problem is not the children. The problem is our inability to create the conditions that foster good teaching and learning. That’s what we should be focusing on, how to create those conditions to enable our teachers to be effective at what they do and our students to ensure that they are learning.” ♦

Pedro Noguera can be reached through the UCLA website, by following him on Twitter, or by visiting his website, pedronoguera.com. Learn more about the work of the Center for the Transformation of Schools at their website, transformschools.ucla.edu.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Thanks for this. Each of this warrant more space, and I hope that this continues the most important conversation in Ed.

All great points and I completely agree with most of them as a high school math teacher in a Title 1 school…. however… the one question I have is with part 10… I completely agree that we need to do a better job at teaching students the way they learn best…. However…if we remove lecture, especially from the upper high school setting, are we then setting our kids up for failure for when they enter college and have little to no exposure/training/skills in how to learn from their college professors whom most will merely only lecture at them? (Especially in those big 300 to 500 person lecture halls). I feel like that is the epitome of failing our kids – if they have never been exposed to lecture and taught how to gain information from it. There has to be a point in high school education where some lecture is actually beneficial. Either that or post secondary education needs to change dramatically.

I see your point — not preparing them for that environment would be doing them a disservice, and I think giving older students some practice in note-taking from lectures is valuable. But that could be just a part of their day-to-day experience in school, where they can learn and grow from a variety of teaching practices, rather than the daily fare.

I think the common misunderstanding when it comes to classroom practice is that one is expected to throughout all of the “old” in exchange for “the new”. I have noted that the best classroom teachers offer multiple access points for students to learn and demonstrate knowledge. The problem with so-called traditional educational methods, particularly in upper grades and college is that lecture sometimes becomes the primary method of delivering instruction. Students are made stronger when they experience multiple methods of instruction and assessment. Taking notes and learning how to follow a lecture is an important skill that needs to be taught, and kids need the chance to learn and practice taking notes; more importantly, they need to figure out what methods of note-taking work best for them. Ironically, to eliminate a student’s exposure to a skill that is vital to higher education success, in essence, creates yet another inequity.

I so completely agree with this, Sam. While I do agree that students have different and preferred learning styles, there is a certain level of student responsibility for older students. I often tell my high school students that lecture is a part of college. Learning to pay attention in every setting is a responsibility of secondary, and post-secondary students.

Jen, attended a conference this summer with equity as one of its primary strands and can still see the lady standing after a day of race and religion speakers in a Ted-style talk day and asking what about my kids, don’t they deserve equity too. She was a special education teacher. I found it an important insight we need to consider.

Thank you so much for this post, Jenn! I am part of a team of teachers organizing a conference on this very topic as it relates to social studies and history pedagogy. Our conference seeks teachers from across the K-16 continuum who want to talk about culturally responsive pedagogies in our social studies/history classrooms, from grade school through college. We invite you to submit a proposal or to just come and join the conversation! Here is the link to our May 3-4 event at UCLA:

https://centerx.gseis.ucla.edu/event/teaching-history-conference/

I love the idea of using community service strategies to address discipline issues. Not only does this eliminate the negative impact of kids missing instructional time, it can help foster empathy and kindness in our children.

I totally agree!

This session is very informative.The breakdown of the 10 ways we can take action,is invaluable.

How do you reach unreachable parents, those parents who lack parenting skills and do not understand their role as a parent and will not participate in their child’s educational journey?

Hi Laurie,

Making strong parent-teacher connections isn’t always easy, but from my experience, I’ve never met a parent who didn’t want the best for their child. If you haven’t already, take a look at some of the resources on our Working with Parents Pinterest board. Browse around and see which resources might be relevant.

Thank you so much for the valuable information. The 10 ways educators can take action in pursuit of equity.

I think that it is crucial to involve parents since they share the same goals with the educators. If both interested parties- parents and teachers- cooperate we can achieve the optimal results.

It is also of primary importance to explore the ways students learn and adjust our teaching methods to them rather than the other way round. Educators have a range of teaching methods and they have to use the most effective ones to achieve learning.

Last but not least, teachers have to research evidence based practices, implement them in their classrooms and check their effectiveness. Important researchers in the field of education have a lot to offer but we should critically evaluate their findings, since not everything succeeds in every case.

The information provided in the “10 Ways Educator Can Take Action in Pursuit of Equity” is absolutely educational, informative, and insightful. Dr. Pedro Noguera fully explained in detail a wealth of information that is so beneficial and equitable for educational purposes.

In addition to that, he said that the first thing we should first look into is “Awareness.” He said, “Homework is also an equity issue” because some students have parents that guide and encourage and supervise their children with their homework while we have some children whose parents are either illiterates, or uneducated – while some parents don’t even have the time to assist their children because they have to work and provide for their family-especially single parents, and some parents even have language barriers and some are of a low social-economic class. He said that some issues affecting the educational system in terms of equity are systemic racism, opportunity gaps, school push-outs, and lack of qualified teachers.

Furthermore, I like where he mentioned that immigrant students should also have the same access and inclusiveness to equal education; the language -barrier is also an issue for the majority of them, and we must not allow language as a barrier that would prevent them from getting the proper education that they need.

Dr, Noguera said that “Aspirations and influence should be provided to students along with good guidance so that they can engage more for them to become good learners.” In addition, Parents, and educators should show and create awareness to children about the importance of education. I like the fact that he said that there should build partnerships to address student’s needs and encourage collaborations between school administrators, principals, teachers, students, and the community, and even churches and other non-profit organizations can take part in the pursuit of educational equity, and as. I also love the idea that we need teachers to teach students in the way they learn best, and teachers must also teach students to adopt the habits of taking notes in the classrooms.

We are so glad that this post was valuable to you. Thanks for sharing!

I’ve taught at a Title I school for 17 years. It wasn’t that way when I started. We’re a sanctuary city and it seemed to happen overnight. We learned quickly how to serve our Latino population and we made many mistakes and called in professionals to help us. We became an AVID school and I feel like that made a huge impact on our school and our students. Everything in this podcast was informative and reinforced the moves we made with homework, learning styles and most of all, parent involvement.

I really like the point made about Building relationships with parents based on shared interests, and Embracing Immigrant Students and their culture. I currently have a student from Afghanistan whose family struggles with American culture and all of it’s language. It’s about finding a common ground that you can build your relationship around. I have found their student engaging, and curious about all things American including his love of pottery.

#5 – Building partnerships with parents –

The quote, “It is very rare to find a student who is successful who doesn’t have parental support.”

It is possible, but indeed very rare. It is also difficult in a lot of those cases to get parents on board, especially at the high school level.

Kindly send me relevant materials on equity in education

Hi, Walter! The Cult of Pedagogy website actually has an entire section devoted to posts about equity in education. I hope this helps!

This interview was one of the most informative and simple to understand, I heard in a while. I loved how every point was explained with multiple examples. Thank you!

We’re so glad the post resonated with you.