A Day in the Life of an Alternative High School Teacher

What everyone really wants to know is if I teach THOSE kids—the mean ones, the dangerous ones, the ones that are “too far gone to save.”

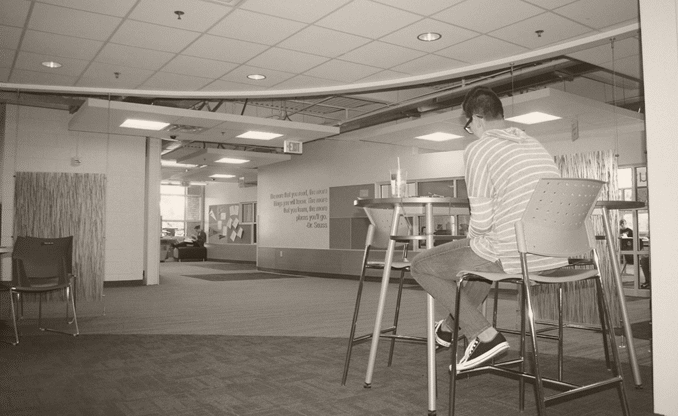

I hold my ID over the buzzer and see the sun peeking over the roof of our building; it’s my last chance to regroup my brain before the day begins. As I round the corner into my hallway, I see students seated in hubs we have around the school and greet them with a smile, even though I don’t feel particularly bubbly at 7:30 a.m. Most return the smile, a few will say “good morning,” and sometimes all I get is a small nod in return. I’ll take it. They’re only slightly zombie-fied, some with McDonald’s breakfast and others sipping their caffeine of choice. Headphones placed over their heads—the big ones, covering their ears like ear muffs—they let out big laughs at whatever the current Internet video brings out of them.

Welcome to (alternative) high school.

A student reads in one of the collaborative spaces in our

newly-remodeled building, designed by teachers and students.

As I write this, I’m just getting into the thick of the year—the newness is starting to wear off and the haggardness is starting to set in, as almost every teacher knows to be true of the end of the honeymoon period. When someone asks me what I do (typically at big social gatherings where small talk is rampant), I hate how limited “I work at an alternative high school” sounds. The person pauses and tilts her head, trying to think of a tactful way to ask what she’s actually thinking. It comes out as “Oh, what does alternative mean?”

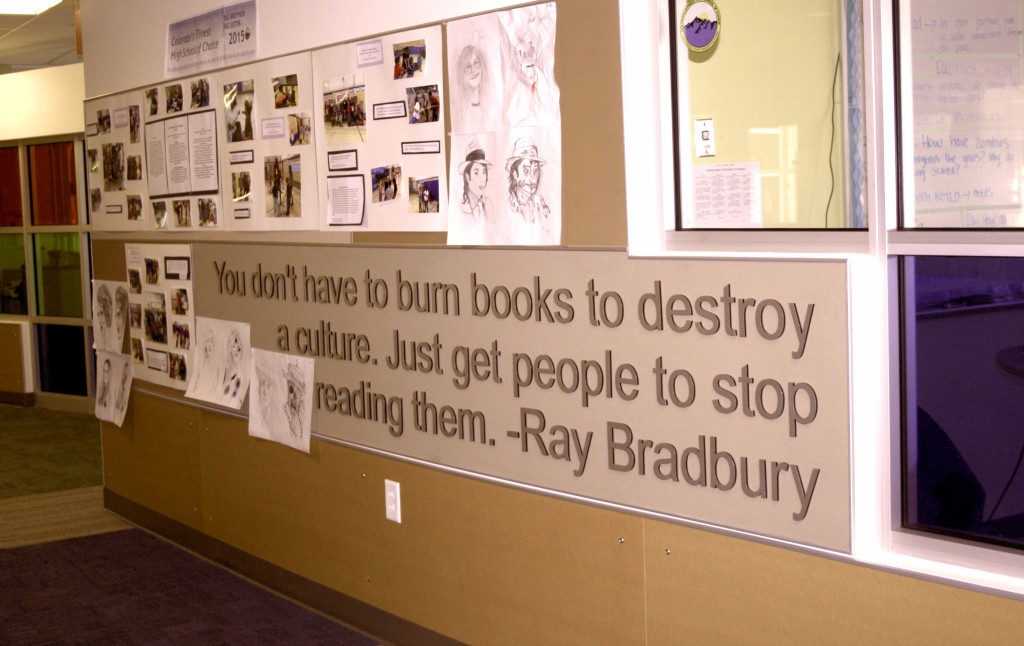

Quotes cover the exterior “walls” of our classrooms—this is one from the English hallway.

Teachers chose the quotes while the building was being remodeled.

What everyone really wants to know is if I teach those kids—the mean ones, the dangerous ones, the ones that are “too far gone to save.” I’ve learned that the word “alternative” can mean different things to different people, so I have perfected an elevator speech. It goes like this:

“Our school has been around for about 30 years, and we offer a place for students to learn in a non-judgmental and caring environment. Students do not have letter grades but have points they earn for each class every day. If they do not demonstrate their learning, they do not get their point. Teachers have a group of students called a ‘family’ that they are with until they graduate. Teachers act as counselors for their students, advocating for them in all stages of their high school career.”

Even that is too mechanical, too rehearsed, and almost painful: I know it is only skimming the surface of the vast history and culture of our school.

What I want is to show the work that our school does, to add depth to the term “alternative.” A passion of mine, and of many other teachers, is to share the stories that fit into the one big story of public education—especially when so many others tell our story, terribly, for us and without our permission.

So, let me get started with the structure of our program.

The Curriculum

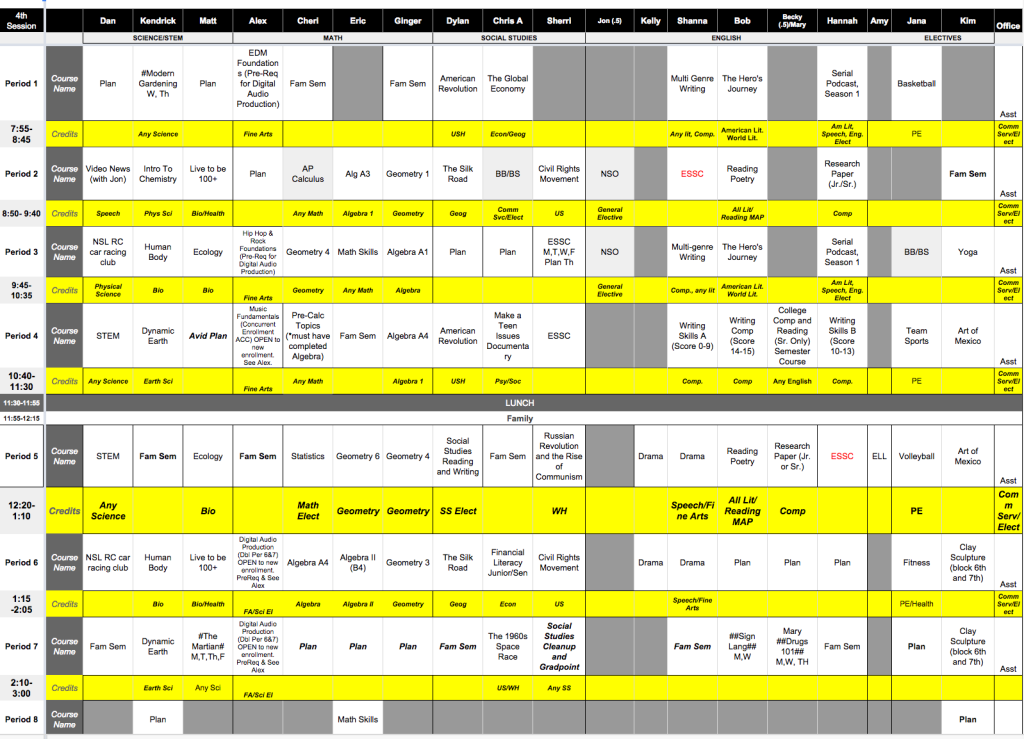

Courses are offered in six-week blocks; a full school year is comprised of six of these sessions. Teachers get to choose which classes we will teach for each session, and students are free to choose their own classes.

This autonomy for teachers (and students) with the schedule is crucial. Whatever I believe needs to be taught, along with my department, is what I teach. For example: I noticed that our students would connect really well to the thoughts and ideas of the Transcendentalists, so I taught a class on that. I put it on the schedule, and the students elected to take it for part of their American Literature credit needed to graduate. If they didn’t think Transcendentalism was going to be something they could engage with, they took a different class. It’s similar to the way college students select their classes.

Course offerings for one 6-week session.

(Click to open a larger view.)

This flexibility allows teachers to create curriculum that is relevant, essential, and engaging to our students, as long as it is connected to Common Core standards. Classes that have been taught in the past include: Designing a LEED-certified greenhouse (STEM), Serial Podcast (Am. Lit/Elective), Yoga (Health/PE), and The History of Terrorism (World History). Imagine a school where nearly each student has choice and is excited about what they are learning. They are not “sent” here; they are not “put” in classes. Of course, sequential and required classes such as math are not as flexible, but a student can choose when they take math (for example, if they are groggy in the morning and would perform better in the afternoon, they have the ability to make that decision).

The flexibility and authenticity of our schedule is something that drew me to teaching here. And you won’t find the typical grading system you would see in a high school; instead, we have a point system. This is where I lose most people in my elevator speech.

The Point System

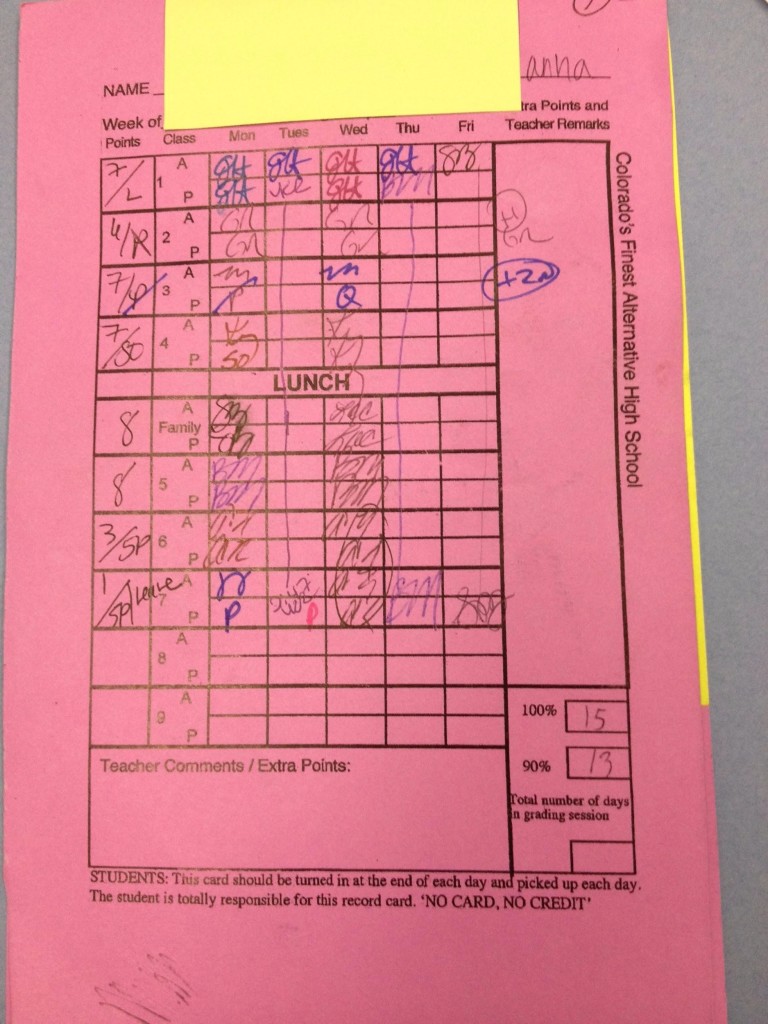

A key part of our school is points—not grades. Students must have 90 percent of their possible points to stay in good standing in the school. To get their point for every day, they must be present and must demonstrate their learning in whatever way the teacher is planning that day; whether it’s a quiz, a project, writing, a reading assignment, or some other activity. This system puts the onus on the student to engage and learn.

Points also provide effective feedback about student behavior. If they are doing things that interfere with their learning—such as being on their cell phones, chatting too much, or being off-task—they do not earn their point for the day. They do, however, have the opportunity to earn the point back the next day.

With the card, two signatures per day per class equals one point. At the bottom, there is the total for 90 and 100 percent. Students are responsible for knowing if they are or are not at 90 percent. Any other symbol below it means they are going to make the point soon (quiz, project, etc.). There are also disciplinary symbols (“SO,” which you see on this card, means the student “sat out” or did not participate). Students have the opportunity to make these back in the time given.

Students carry a point card with them throughout the day.

The A stands for attendance, and the P stands for participation.

With this model, every day students are making points to graduation. For many of them, taking it one day at a time helps them see the big picture of eventual graduation. Seeing the amount of control they have over their education—for better or worse—is one gigantic paradigm shift.

My Daily Schedule

For my schedule, I teach straight through the morning into the period following lunch. I’m an English teacher, primarily writing, but I cover everything from 9th to 12th grade. I teach six classes a day, and I feel privileged to work with the students I do. Because our school attracts students from all areas and levels, I have a lot of differentiation on my hands. In any given class, I could have one student who reads at a 7th grade level, and another who reads a college level. This is fairly normal for our program, which is why class sizes under 22 students are necessary.

That’s me with part of a debate team for my argumentative writing class.

We were debating whether the drinking age should be lowered to 18.

After lunch comes family, a kind of advisory period when we update students on what’s going on—special schedules, registration, college visits, etc. It’s also a time to bond and do some team building. Many schools struggle with things like cohesiveness in school culture. In ours, the culture and connectedness of our school is driven by family. Each family has about fifteen students per teacher, and meeting times are about 25 minutes long.

The responsibilities of being a family teacher include registering students for classes, calling parents, and staying in constant communication with students, helping them work through personal and social issues, and performing interventions. Students stay with the same family teacher throughout their four years at our school, so when the time for graduation comes, the family teacher is the one to hand students their diplomas. Currently I have about five seniors—my year will be busy writing letters of recommendation, making sure they have applied to college, and filling those gaps before they leave.

Students take direction from the drama department’s director.

The last class I help teach is drama. We are fortunate to have a program that we just started this year. So far, we have put on one student-written and student-produced play called A World Gone Mad, a mashup of fairy tales. My role is to assist the director in anything that needs being done—attendance taking, managing students, logistics, and to be an extra set of eyes.

After this class is over, I’m done teaching for the day. The last couple of hours are for handling any issues within my school family, attending staff meetings, and fitting in some planning time if I’m lucky.

Students paint a backdrop for an upcoming drama production.

When Problems Arise

On this particular day, I’m giving up some needed planning time to attend a meeting called an “Appeals” for a student who got into a verbal altercation with another student, which breaks one of our three golden rules—no anti-social behavior, make 90 percent of points, and no drugs or alcohol.

The student sits in the conference room, tense. She is staring at the table. A group of teachers trickle in (whoever was involved or wants to be there, plus the family teacher) to serve as part of the appeals board. They make casual conversation to lighten the mood—usually about something funny that happened to them, or the weather. Someone is tapping their pencil.

The meeting gets started with one question: Tell us why you’re here today.

The student begins quietly with her explanation; she’s remorseful. We learn that she’s been working late into the night so she can save money to move out of her house. It’s not a place she wants to be. She’s angry at herself, but she apologizes. The teachers make notes, ask more questions, offer her encouragement. Ultimately, the student must make the case to us that she can stay in good standing with our program if we let her come back. She insists that she will. She’ll be at 90 percent—100 even—and will not have any more broken golden rules. If she does, she’s not a student at our program.

This accountability piece—that students must show their willingness to succeed and control their actions the best they can—is crucial. They see attending as a privilege that is not guaranteed. They have to work, and in turn we work just as hard—and then some—to make sure they have best opportunities they can once they leave.

Art is a large interest for many of our students—our school and students have won

many local and national awards. These particular pieces are foil etchings.

We allow her to return, provided she does not have any more broken golden rules. The mood is lighter; a small smile returns to her face. We ask her some other questions—How’s your mom? Is your car running OK? We tell her we’re excited to see her back next week. She knows she’s lucky; not all students return if they are on an appeals.

The End of the Day

After the meeting is over, I’m exhausted. These meetings reveal so many underlying things about our students—abuse, addiction, family problems, medications, insecurities, strengths, interests, dreams—and it does take an emotional toll. I reluctantly stand up, stretch my legs, and head to my office. Once there, I muster some motivation to use the remaining day to do the things we all have to do—call parents, answer emails, give feedback on assignments, and decide my personal favorite: “What am I teaching tomorrow?”

It’s a good exhaustion. The kind that makes my body feel heavy and my head swim with all the thoughts propelling me to tomorrow—dreading it, but also hungry for learning more about myself, about teaching, about my students. I wouldn’t be anywhere else. ♥

Join the Cult of Pedagogy mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. To thank you, you’ll get access to our Members-Only Library of free downloadable resources, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading!