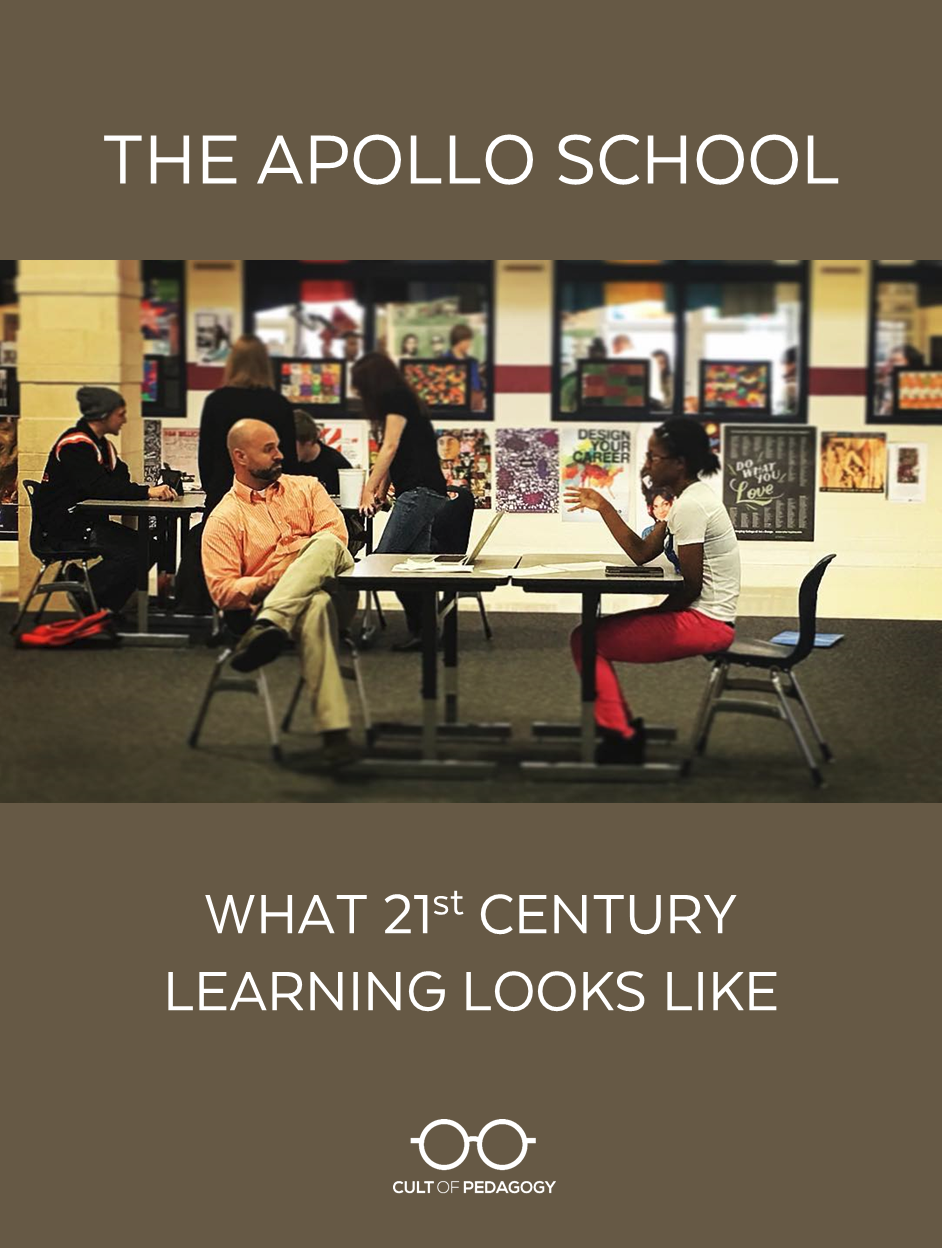

The Apollo School: What 21st Century Learning Looks Like

Listen to my interview with the Apollo School founders (transcript):

We’ve reached a point where most teachers embrace the idea of student-directed learning, the philosophy of being the guide on the side rather than the sage on the stage. We can also appreciate the value of cross-curricular studies, blending math and science, for example, or integrating arts and music into history class. So why are so many teachers still using the same old model, where we plan and deliver lessons in separate subjects, in lock step, using the same traditional schedule as we always have?

Two reasons, I think.

One, because it works, more or less. We move students through the system, they learn some stuff, pass tests, and graduate with an acceptable repertoire of knowledge and skills. Acceptable. Enough to function, to continue on to college and survive, more or less.

Except that lately, more and more voices are telling us that this repertoire of knowledge and skills isn’t quite cutting it. Students aren’t quite as adept at problem-solving and collaboration and inquiry as they need to be for the 21st century.

The other reason we stick to the traditional framework is the one I believe is more powerful: It’s because we don’t know how to change. We have no template for what school could look like if we restructured it to reflect priorities like cross-curricular connections, student self-efficacy, and inquiry-based learning.

Well, I have a template for you today, and I can’t wait to show it to you.

Welcome to the Apollo School

The Apollo School is a program that operates inside a regular public school, Central York High School in York, Pennsylvania. Apollo is a semester-long, four-hour block of classes—English, social studies, and art—all blended together and co-taught by three teachers, one from each subject area. Throughout the semester, students are responsible for designing and completing four major projects, each of which is aligned with standards in all three subject areas.

Students set their own goals for each day based on whatever project they happen to be working on at the time: This includes independent and group work, one-on-one appointments with teachers, and attending optional, self-selected mini lessons taught by the teachers. By lunch time, when the Apollo block is over, students resume a regular schedule for the rest of the day.

How the Program Started

Apollo began when Greg Wimmer, a social studies teacher, and English teacher Wes Ward (pictured above), started playing around with the idea of combining their two classes. “Every time I would teach a piece of literature,” said Ward, “I’d find myself talking about history. And I thought how convenient it would be—and really beneficial to the students—if they could have a history buff here to really challenge and push the kids to dig up more context of the poetry or stories we were reading.”

Meanwhile, their school district was already shifting its whole instructional paradigm. Embracing an approach called mass customized learning, Central York School District was looking for ways to personalize the learning experience for every student. This approach was influenced by the work of Bea McGarvey and Charles Schwahn in their visionary book Inevitable: Mass Customized Learning: Learning in the Age of Empowerment.

This video explores that district-wide shift:

With encouragement from their principal, Wimmer and Ward joined forces with Jim Grandi, Central York’s art teacher, and the Apollo School was born. They gave a presentation to prospective students the semester before the course started, and interested students in grades 11 and 12 enrolled voluntarily.

Central York still offers traditionally taught English, social studies, and art classes. This choice is all part of the variety offered by mass customized learning. “We have some courses that run in a hybrid format where they may meet with a teacher for a little bit but then be working independently or in groups, and then they’re meeting back with the teacher again,” explains Ward. “We have online courses where students check in once a week with a teacher, but the rest of the work is done online. So mass customized learning isn’t necessarily Apollo. Apollo is one spoke of that wheel.”

Course Requirements: Curriculum and Assessment

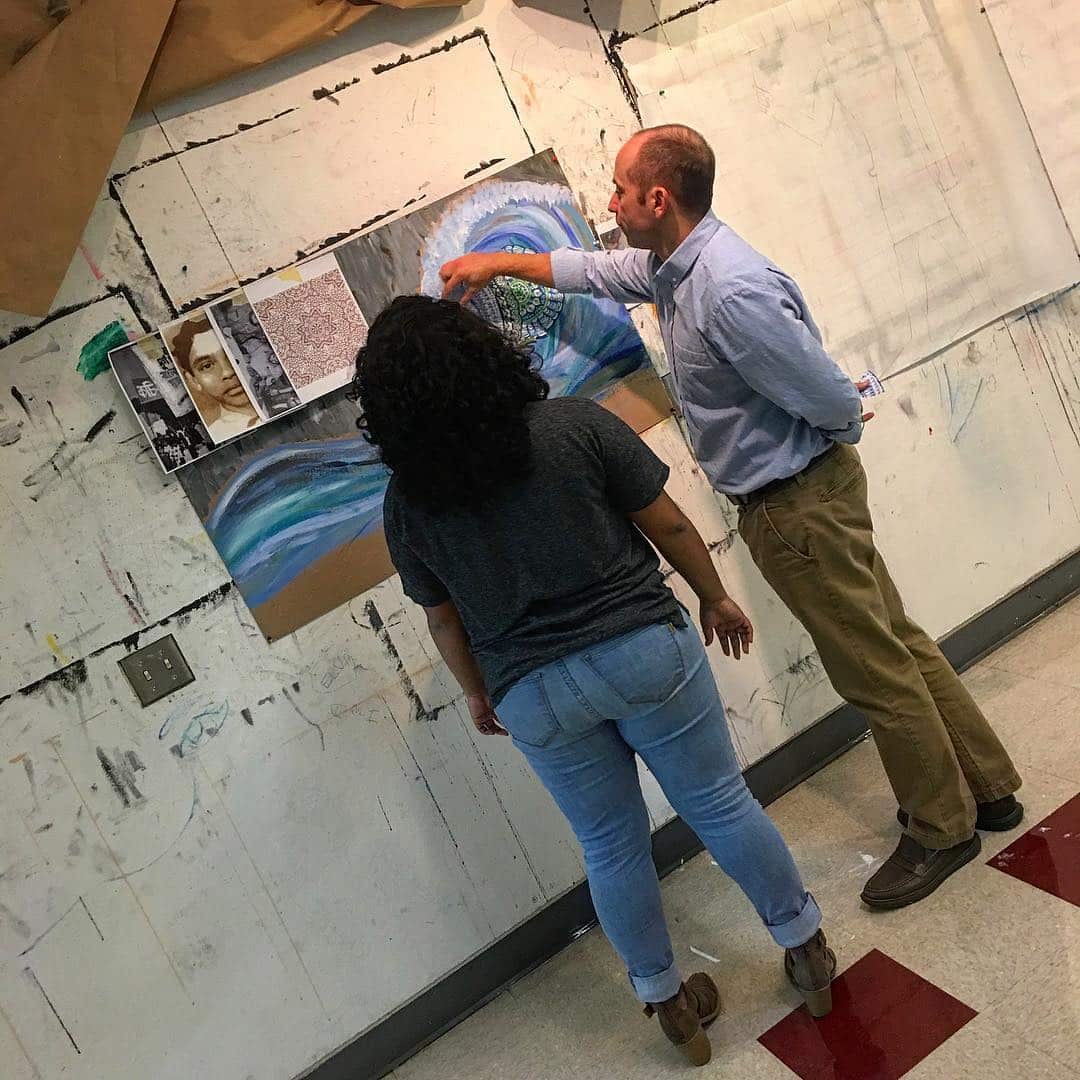

Over the course of a semester, Apollo students are required to complete four independent projects within a given theme, each of which must include some element of English, social studies, and art. Students are given a list of the required standards in every subject, and they are expected to meet each of these by the end of the semester.

“Since you have 40 students running in 40 different directions,” Wimmer explains, “we decided they were the ones that needed to self-select the standards.”

Ward describes how the process works. “At the start of every project, we have the students kind of designate which standards they’re going to work towards, either showing mastery of or just practicing to get better at. Unlike most classrooms where the teacher is drawing up the lesson plans based on standards that are some invisible thing under lock and key, we actually share PDF files of all three of our subject area standards with students. They have them all semester long, so they’re constantly aware of the expectations from each of us and what they’re supposed to be mastering.”

How students meet these standards is entirely their decision, and the road is not always smooth. “It’s really genius to see them a week into their project realize that they’re hitting the wrong standards,” Wimmer says, “and then they go back and are able to change them and make the standards work for them.”

When a project is completed, students meet with all three teachers in a setting not unlike the defense of a doctoral dissertation: They discuss goals, process, and outcomes, and explain exactly how they met each learning target. Students are also assessed on how well they met four thinking skills—reasoning, perspective, contextualization and synthesis—and two “soft skills”—communication and time management.

The whole group meets at the beginning of each day in Family Time.

A Typical Day

Each day starts with Family Time. “Around 7:45 we kind of corral them together into Greg’s room and we call that Family Time,” says Grandi. The length of that meeting can vary dramatically, from five-minute housekeeping sessions to hours-long conversations. “We’ve had full-on one hour to two-hour discussions where they’re really generating the conversation and driving the topic about their own education. Those can be completely organic in that sense, and really rewarding.”

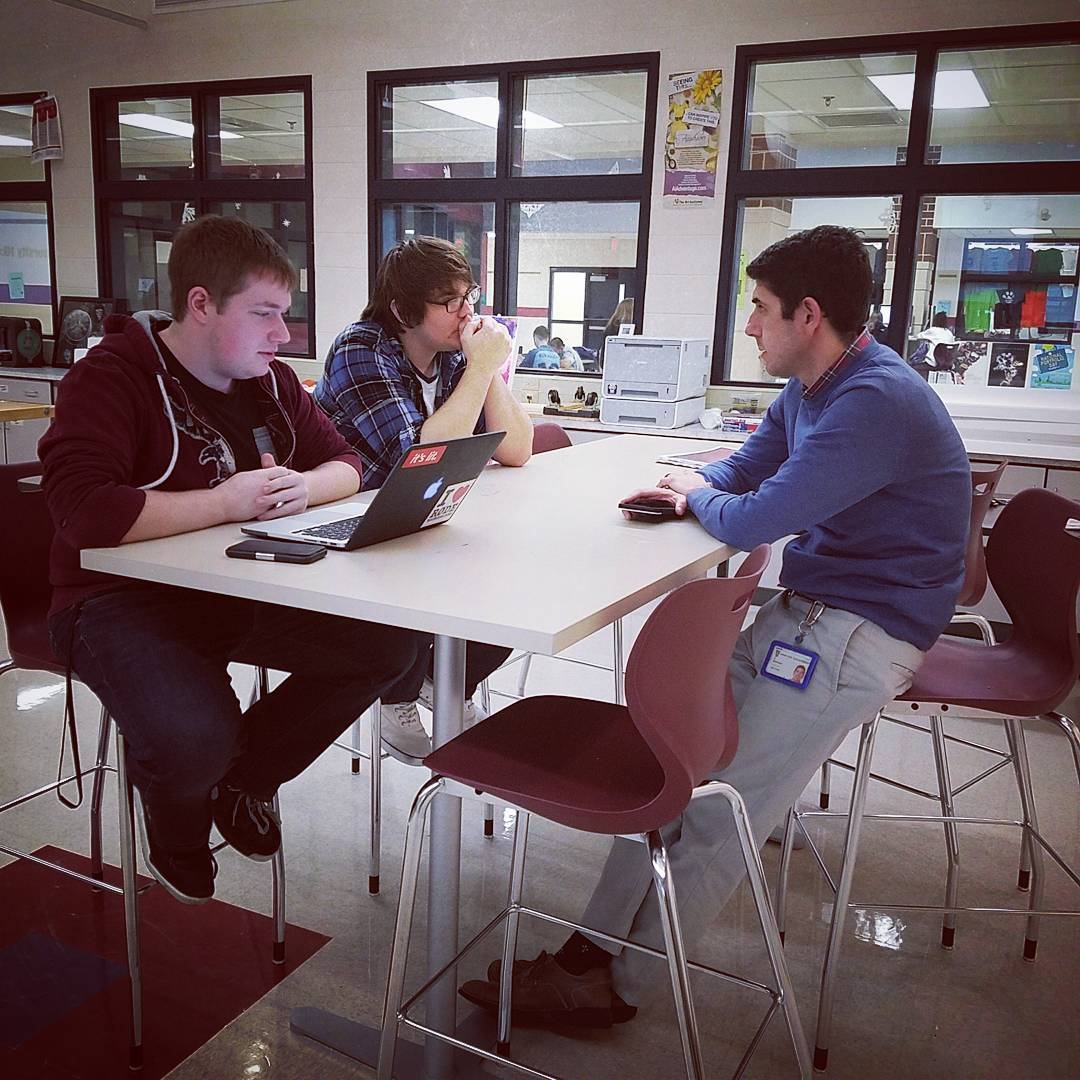

Students use online software to plan out how they will use the four hours, in 30-minute blocks of time. This time might include independent research, creative work, group work, or one-on-one conferences students schedule with the teachers as needed.

Students meet with social studies teacher Greg Wimmer. Using an online form, students schedule one-on-one conferences with teachers as needed.

They are free to travel between the art room, which functions as a kind of makerspace, Wimmer’s classroom, which students typically use for small group meetings, and Ward’s room, which is often used as a quiet space for students to work alone.

“They can also go to our library or sit at one of the tables that’s around our school and in extreme situations,” Ward says, “they might even leave the school to go interview somebody in the community or to go shadow somebody in a certain career. We really try to push them beyond that normal setting.”

Each student decides how to use Apollo’s four-hour block of time. At the end of each project, time management is part of their final assessment.

Mini-Lessons

Another option students have in that four hour block of time is attending mini-lessons. Rather than teaching whole classes the same lesson at the same time, the teachers plan and teach optional mini-lessons within their subject areas. Some lessons cover basic content areas that meet certain standards, but most are delivered only after teachers see a need within the scope of what students are working on.

Optional. Did you catch that? Students are not required to attend mini-lessons; they choose to go based on their current needs. During family time, the teachers will advertise the lessons they are teaching that day.

“It’s kind of like going to an education conference and having that smorgasbord of possibilities to choose from,” Ward explains. “So it’s entirely possible that Greg would be teaching a lesson about this particular conflict or this issue in current events. And Mr. Grandi might be offering an art lesson at the same time that I’m offering something in English, and the students get to pick and choose which one is more beneficial to them in their project at that point in time. We can turn around and offer the same lesson the next day, and they can switch and go to the other one, if need be.”

The customization doesn’t stop with the teachers: Students can also request mini-lessons on specific topics. Grandi recently had a student request a lesson on Frida Kahlo and other artists inspired by her. “So I said, ‘Yeah, just give me two or three days to put that together and then I’ll have that lesson for you.'”

Some mini-lessons are even taught by the students themselves. “Every student usually has something they can add to the group,” Wimmer says. We have some students that are extremely good at technology, some who are good at building an online presence, and so we thought, why not have those students share their abilities and talents with one another?”

Art teacher Jim Grandi conferences with a student. Each student project includes an element of English, social studies, and art.

Positive Outcomes

When asked whether the program has produced the results they’d hoped for, Grandi says students go far beyond what they’d be able to do in a more traditional program. “When I’m teaching traditional classes, I try my hardest to plan really interesting lessons and projects for the kids to do. But I can’t plan these projects. I could never plan a bioethics project for the whole class. I couldn’t even hit all of the standards that I wanted to it. This way, (students) hit more standards as a class than I would ever have them hit if I was directing every single lesson.”

Academics aside, the program has allowed teachers to develop the kind of relationships with students that just wouldn’t be possible in a regular setting. “We’ve had some of these young adults come up to us and just … things I’ve never even thought I would hear,” Grandi says, “about how they would be scared to death to come to school Sunday night from anxiety, and how they love coming to school now, and they never have had conversations with adults or their teachers before, more than just, ‘Here’s your homework, here’s your test.’ We have real conversations with these people, I mean, these are people. The relationships you build are amazing.” ♦

Learn More About the Apollo School

Website: theapolloschool.weebly.com

Instagram: @apollocyhs

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll also get access to my members-only library of free downloadable resources, including my e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading!