How to Turn Rubric Scores into Grades

I have written several posts about the different types of rubrics—especially my favorite, the single-point rubric—and over time, many teachers have asked me about the most effective way to convert the information on these rubrics into points. Even if you are moving toward a no grades classroom, as a growing number of educators are, you may still be required to supply points or letter grades for student assignments.

Despite the title of this post, all I can really offer here is a description of my own process. It has been refined over years of trial and error, and the only evidence I have to back up its effectiveness is that in over 10 years of teaching middle school and college, I can only recall one or two times when a student or parent challenged a grade I gave based on a rubric. This is by no means the only way to do it—I’m sure plenty of other processes exist—but this is what has worked for me.

Before I get into the specifics of the scores themselves, I’m going to describe all the things that happen before those points go into the grade book. I’ll do this with an example scenario: Suppose I want my eighth-grade students to write a narrative account of a true story. This will not be a personal narrative, but rather a journalistic piece that illustrates some larger concept, such as the story of one student’s chaotic after-school routine to illustrate the problem of some kids having too many activities and homework after school.

Step 1: Define the Criteria

To start with, I have to get clear on what the final product should look like. Although I have my own opinions of what makes a well-written story, I need to put that into words so my students know what I’m looking for. Ideally, this criteria should be developed with my students. Any project will be more effective if students are part of the conversation from the beginning; I would ask them what makes for a good story, what kind of criteria should be used to judge its quality, and so on. To generate ideas for this discussion, we would first read a few examples from magazines and websites of the type of writing I want them to produce, and we’d figure out what qualities make these stories work. Eventually we’d shape these ideas into a list of attributes for the rubric. (Full disclosure: This is an ideal scenario. I often skipped the step of involving students to save time, but that was ultimately not the best decision.)

I would also consult with my standards and curriculum materials, to make sure I wasn’t missing something relevant and to make sure the language in my rubric is aligned with those standards.

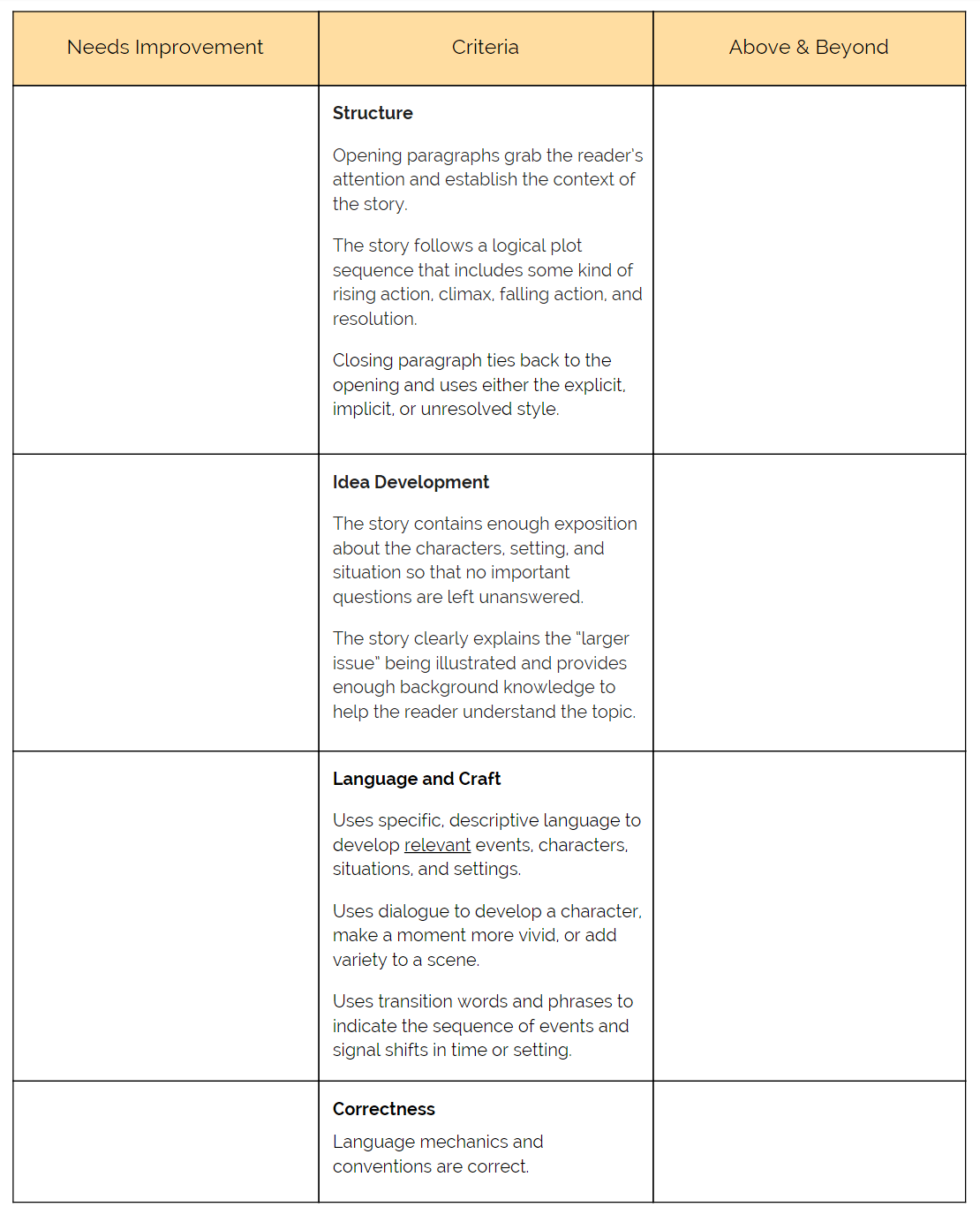

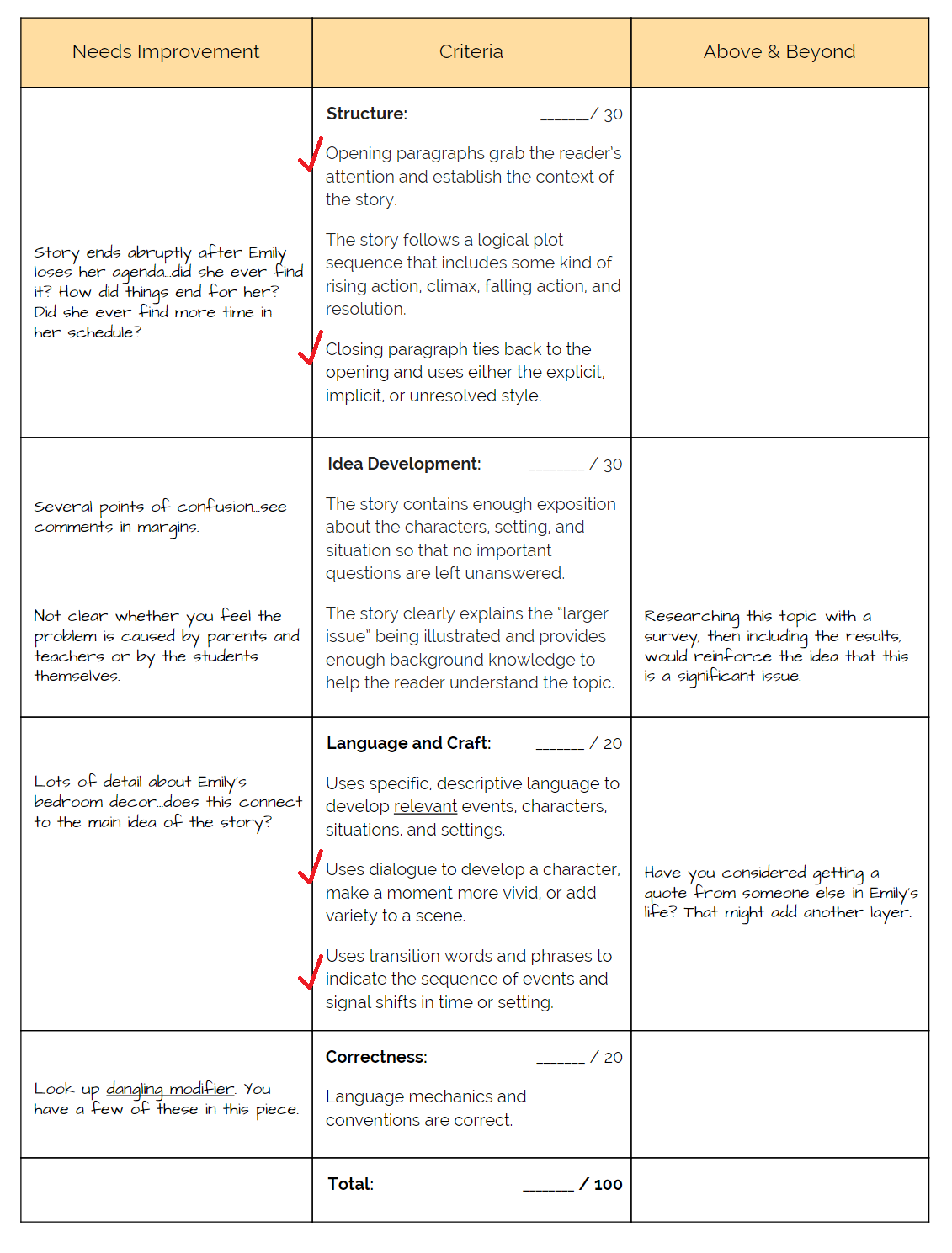

Using the single-point format, my rubric would look something like this:

If you have been working with single-point rubrics, you know that the left-hand column is reserved for indicating how students need to improve. The right-hand column has a different title than what I have used in the past. In earlier versions I titled this column”Exceeds Expectations,” providing space to tell students how they exceeded the standards. I have adapted it here to “Above and Beyond” to make it more open-ended. It can be a place to describe where students have gone beyond the expectations, or it could be a place where the teacher or the student could suggest ways the work could reach even further, a place to set “stretch goals” appropriate to that student’s readiness and the task at hand.

Step 2: Distribute the Points

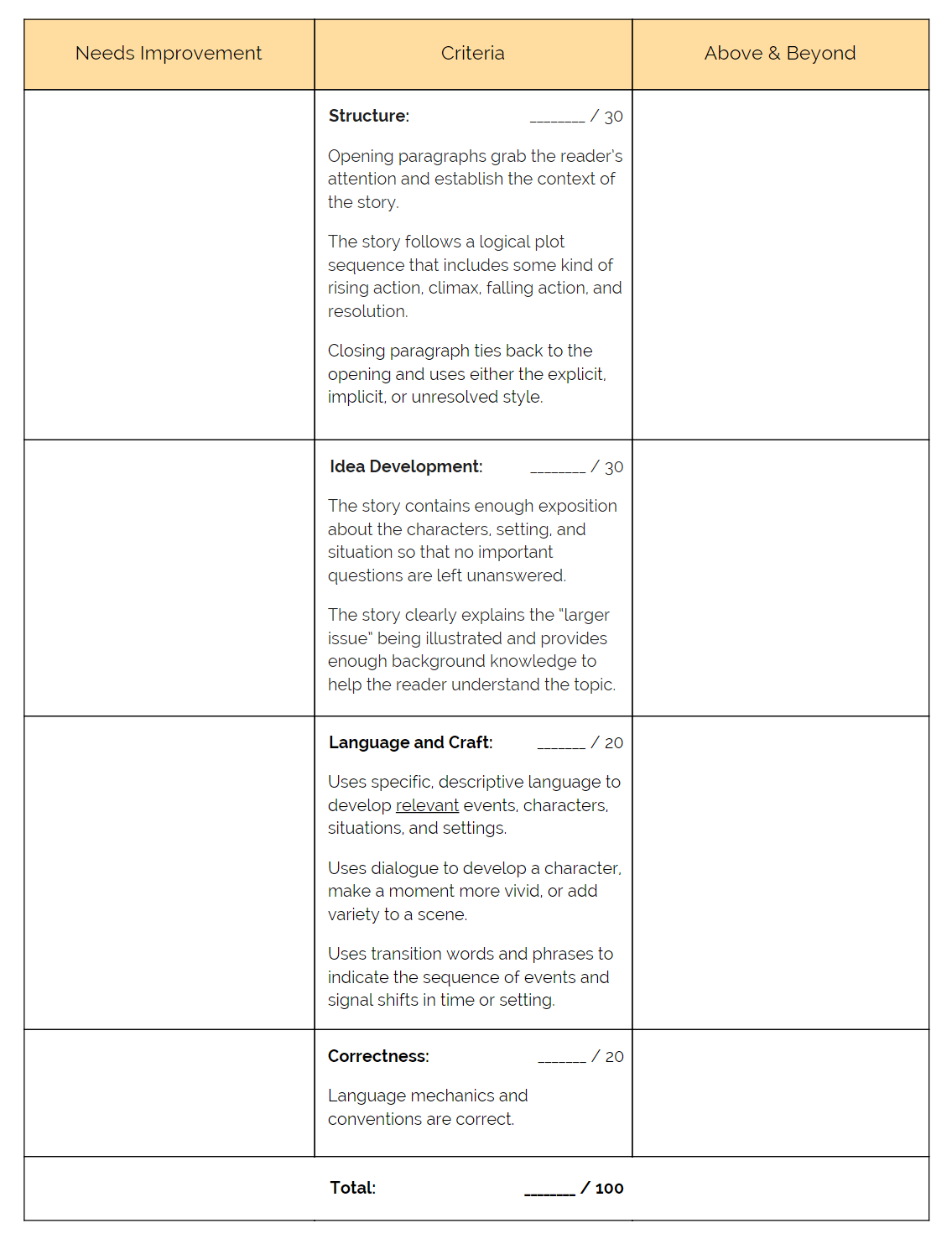

Once my criteria have been defined, and if I will ultimately be giving points for this assignment, I need to decide how to divide those points across each category. Assuming a total of 100 points for this assignment, I would weigh certain components more heavily than others. Because my main goal is for students to write a robust, well-developed story, I would place more value on the top two categories—structure and idea development. This is an area where subjectivity can take over, and where rubrics can really vary from one teacher to another. So again, keep in mind that this is what it looks like for me.

For a 100-point assignment, I might distribute points as follows, adding them right into the rubric with a space for inserting the student’s score when the task has been graded:

Step 3: Share the Rubric with Students Ahead of Time

This part is crucial. Even if students are not included in the development of the rubric itself, it’s absolutely vital to let them study that rubric before they ever complete the assignment. The rubric loses most of its value if students aren’t aware of it until the work is already done, so let them see it ahead of time. I typically provide students with a printed copy of the rubric when we are in the beginning stages of working on a big assignment like this, along with a prompt that describes the task itself.

Step 4: Score Samples

Another powerful step that makes the rubric even more effective is to score sample products as a class, using the rubric as a guide. I often created these samples myself, building in the kinds of problems I often saw in that type of writing. Occasionally I would use a piece of writing from a previous student with their name removed. Ideally, we would score one or two of these as a whole-class activity, and then I would have students do a few more in pairs. This process really gets students paying attention to the rubric, asking questions about the criteria, and getting a much clearer picture of what quality work looks like. When it comes time to craft their own pieces, they are better at using this tool for peer review and self-assessment.

Step 5: Assess Student Work (Round 1)

After students have been given time to plan, draft, and revise their writing—a time when I am watching their work in progress, advising them, and regularly referring to the rubric as a guide—students submit their “finished” pieces for a grade. My feedback for a student who hit many of the marks, but needed work in some areas, might look like this:

I put a check beside the criteria that has been satisfied in that draft, and add comments to the left of those that need work. In the right-hand column, I add a few suggestions for ways this student might push herself a bit more to make the piece even better.

You’ll notice that the space for scores has been left blank. There’s a reason for that: When students are given both feedback and number or letter grades, their motivation often drops and they tend to ignore the written feedback (Butler & Nisan, 1986). My own experience has proved this to be true; I have often spent hours giving written feedback on student writing, but found they often ignored that. Now I know this was because the feedback also included a grade. No-grades advocate Alfie Kohn, in his piece From Degrading to De-Grading, recommends that teachers who want to avoid this effect “make grades as invisible as possible for as long as possible.” With that in mind, in this round, students only get feedback, not scores.

Keep in mind that much of this feedback could be generated with the student, in a conference. If time permits, you could sit with the student and go through the rubric together, noting places that still need work and considering ways to take what’s already working and improve it further.

Unless the student has satisfied all the criteria on this first try, she will have an opportunity to revise her work and resubmit it, along with the original rubric. Those who did meet all the standards have the option to revise; not for a higher score (since scores haven’t been given), but to simply push the piece to an even higher level of quality.

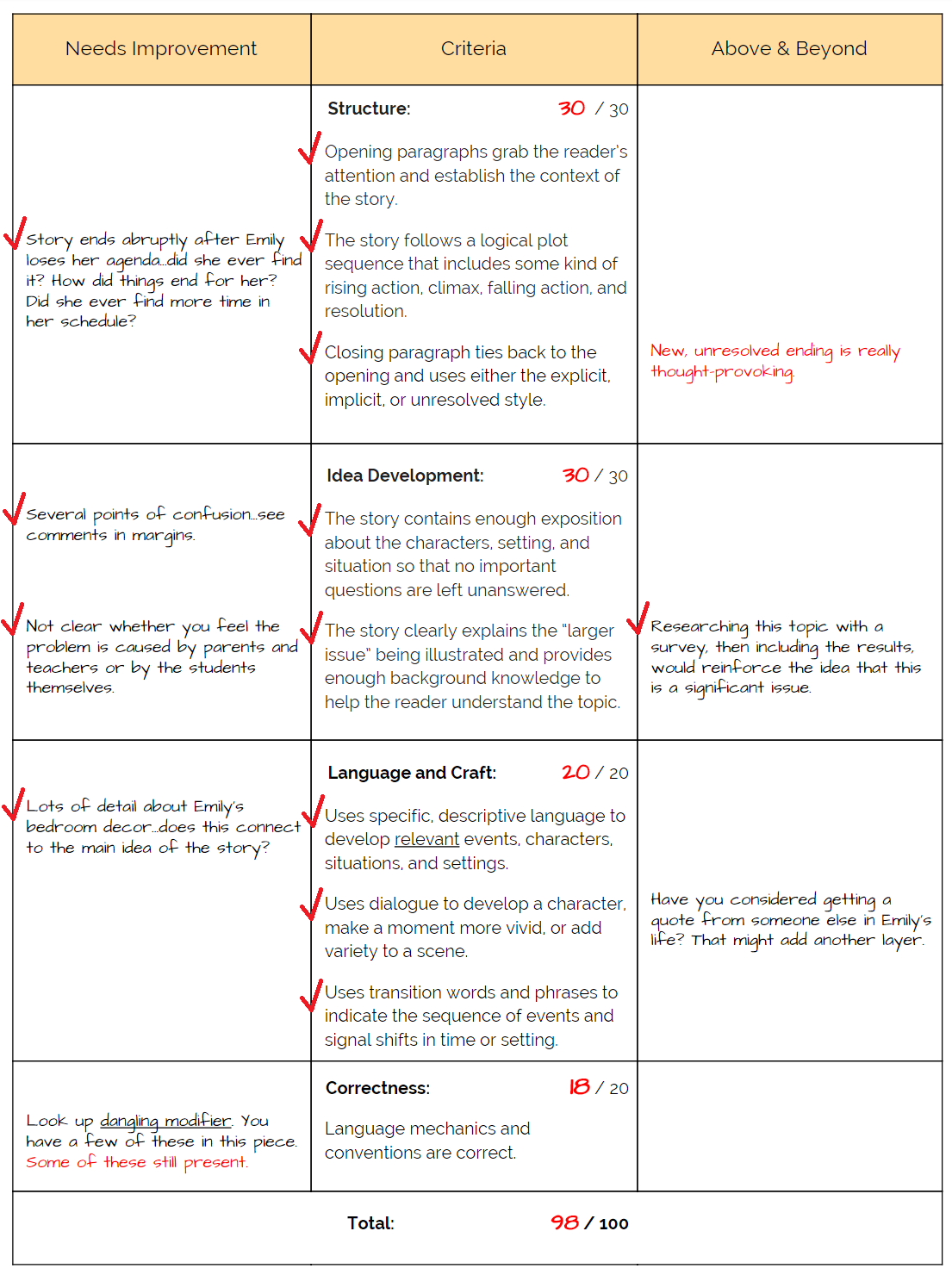

Step 6: Assess Student Work (Round 2)

When students have improved their work and re-submitted it, if they have gotten much closer to achieving the criteria, this would be an appropriate time to assign points to go into the grade book. If the issues raised in the first round have now been addressed, they are given a check to indicate that they are no longer a problem. In cases where all criteria in a category has been satisfied, the full number of points will be given. If a problem persists, new feedback may be added, and a portion of the points will be deducted. Again, this is the subjective part: I try to consider the work as a whole and deduct only a small percentage of the total points for a small problem. Really, if a problem is significant, the assignment should be reworked until that problem has been resolved. Once each section of the rubric has been scored, the points are totaled and that total is the score that’s entered into the grade book.

Q&A About this Process

Will there be a Round 3?

That depends on you and your student. If you feel the student is growing and will put the work in to improve the piece further, and you are willing to assess it again, you should offer another round, and another, if progress is still being made.

Doesn’t this process result in most students getting an A on the assignment?

It definitely could. If a student is willing to put the time in to satisfy all the criteria, then she will get the A. Those who are used to getting A’s will have the option to push their skills to a higher level in Round 2 or will have the luxury of moving on to something else. It may bother some people that two students who may have different skill levels could end up with the same grade, but behind the scenes, the effort to reach that grade could be very different from student to student.

Isn’t this time-consuming?

Heck yeah it is. Well, sort of. For me, this type of assignment would be given over the course of several weeks. By the time I have to actually give points, I have seen that student’s piece many times. I have given her informal feedback while she writes and more formal feedback in Round 1, so the time I put into all the stages ultimately results in a final product that’s much stronger than it would have been as a quick, one-time thing. And that makes the final assessment process much faster.

Doesn’t this result in students being at different stages at different times?

Yes. In many cases, you will find yourself with some students being “done” with an assignment, while others are re-doing it. Most teachers want their students to be learning the same skills at roughly the same time, and unless you are running a very personalized, Montessori-style classroom, you’ll want some kind of consistency from student to student. Consider whether you might be willing to spend only part of your class doing the more lock-step, everyone-on-the-same-page kind of work, but set aside other times for students to work on improving past assignments or doing independent work like genius hour projects.

Need Ready-Made Rubrics?

My Rubric Pack gives you four different designs in Microsoft Word and Google Docs formats. It also comes with video tutorials to show you how to customize them for any need, plus a Teacher’s Manual to help you understand the pros and cons of each style. Check it out here:

References:

Butler, R. & Nisan, M. (1986). Effects of no feedback, task-related comments, and grades on intrinsic motivation and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(3), 210-216.

Kohn, Alfie. “From Degrading to De-grading.” High School Magazine (1999). Retrieved 19 Aug. 2015 from www.alfiekohn.org/article/degrading-de-grading/.

I would love to have you come back for more. Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and joyful. To thank you, you’ll get a free copy of my new e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half. I look forward to getting to know you better!