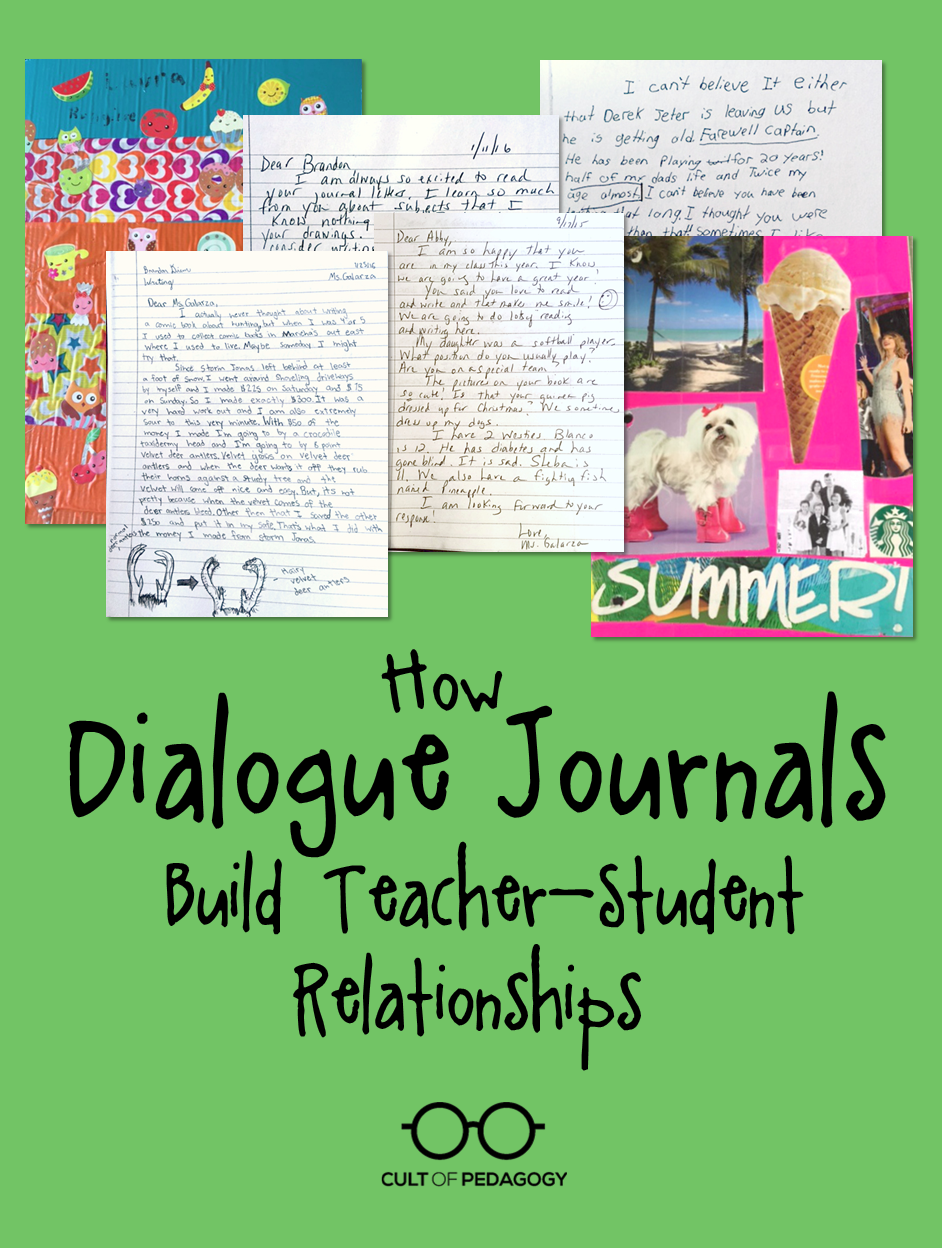

How Dialogue Journals Build Teacher-Student Relationships

Listen to my interview with Liz Galarza (transcript):

How well do we know our students? They sit in our classrooms five days a week, we certainly spend lots of time with them, but how well do we really know them? How well do we know their thoughts, their worries, the things they obsess about? And how well do they ever get to know us beyond our role as a teacher?

Liz Galarza

I’ve been hammering away at the importance of the teacher-student relationship for about as long as Cult of Pedagogy has been a thing, but every now and then I come across a method or approach that can really help build those relationships more effectively.

My friend Liz Galarza, who teaches middle school writing in New York, has been telling me for ages about the dialogue journals she uses with her students and how transformational they have been in building relationships. The journals had such a profound impact that Galarza made them the focus of her doctoral dissertation.

What are Dialogue Journals?

A dialogue journal is any kind of bound notebook where students and teachers write letters back and forth to each other over a period of time. This is very similar to the kinds of journals described in Smokey and Elaine Daniels’ book, The Best Kept Teaching Secret, but since Galarza has had such powerful experiences with these journals, I thought another post was merited.

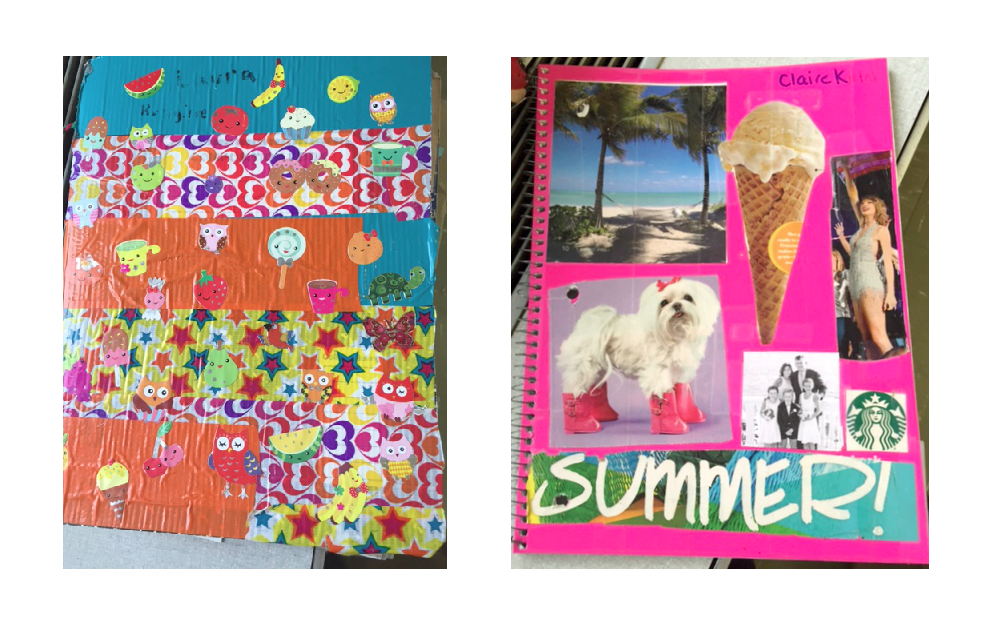

In Galarza’s class, students purchase whatever kind of journals they want, “as long as it’s going to withstand a year’s worth of back and forth,” she says. “Most of them use the marble composition notebooks. I ask them to decorate with pictures or quotes, and it really does show their personality.”

How Dialogue Journals Work

The First Entry

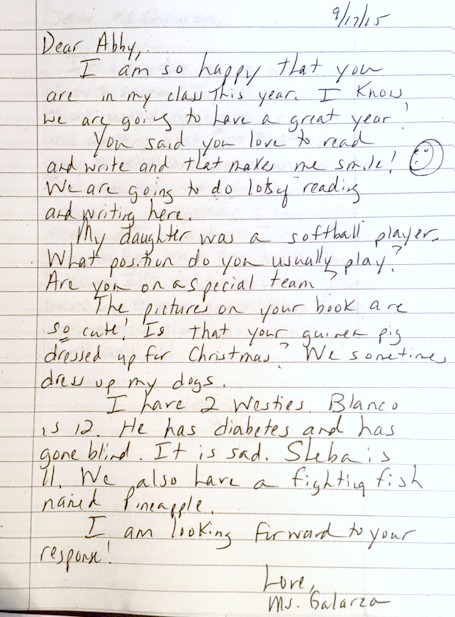

In the first few days of school, Galarza gets to know her students through intake forms (not included in the journals) where she asks students to tell her five things about themselves that she wouldn’t be able to tell by looking at them or their school records. Next, she goes into the journals and writes the first entry, starting with a very general welcome, then beginning to connect with students based on things they wrote on their intake forms.

Although many teachers begin these kinds of journals by having students write the first entry, Galarza has had more success by starting them herself. “I think the kids who have less confidence when it comes to writing would feel paralyzed by that. So I try and make it very, very open.”

In the sample letter below, Galarza connects with this student about her love of reading and writing, softball, and pets. “The first letter I ask more questions than any other time, but I get them to see that I’m human. We have commonalities. I’m interested in you. You’re important to me. This is going to be fun.”

Student Responses

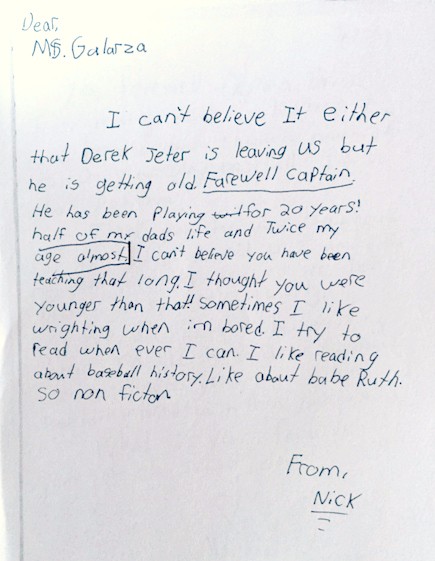

Once the teacher’s first letter is written, students write back. In this sample, Nick responds to Galarza’s opening letter, where she mentioned Derek Jeter leaving the Yankees. “In his intake sheet, every single thing he wrote about was about baseball and the Yankees,” so Galarza made sure she mentioned that in her first letter.

Time and Grading

As the school year progresses, the journals go back and forth between teacher and student. Galarza asks students to write one letter a week, although some students write more often than that. About once a week, Galarza will ask each class period to hand in their journals, staggering these on different days so she only has one class period per day to respond to. She takes about an hour to respond to a single class set of journals, so if it’s a busy season, she may end up only collecting them every two weeks, rather than once a week.

As for grading, students are simply given credit for completion. Even if they don’t write a lot, they get credit for doing it. And that’s it. Galarza does not mark errors or evaluate the work for any kind of score. Because this journal is about building a relationship, Galarza doesn’t want to take away its appeal by assigning a grade to it. “The more often you put a grade on something,” she says, “the less empowering you’re making it for the students.”

Benefits of Dialogue Journals

Shifting the Power Differential: Because dialogue journals allow students to see their teachers as people, they shift the teacher from the “all powerful” role and create a stronger, more meaningful connection between teacher and student. “As a teacher we always have that authoritative stance: We’re the teacher, and they’re the student, and they know that,” Galarza explains. “I think the more you use that as leverage, the less you’re going to get out of students.”

Writing Fluency: When students write in dialogue journals, there’s no pressure to fulfill an assignment or construct perfect sentences. Students just write. And the more a person writes, the more confident they become and the better their writing gets. If the teacher can identify topics that are important to the student, this can inspire far more writing than a student would ever produce for an assignment. Nick, the student above who wrote about Derek Jeter, initially told Galarza he hated to write. After their first exchange about the Yankees, Galarza says the topic stayed with them for the rest of the year, and Nick ended up filling more pages than any other student that year.

Formative Assessment: Although the journals are not designed for this purpose, having students write regularly allows the teacher to spot errors or weaknesses that can inform teaching. “I can use the multiple language errors that I find in many of the journals as a basis for my mini-lessons,” Galarza explains. “So if I see that many of my students are not using commas when they’re offsetting a list, that might become a grammar mini-lesson.”

Individualized Instruction: “You can literally teach them something within the journal without anyone knowing that you’re doing it,” Galarza says. “I’ve said something like, ‘You know, you can use a semicolon in your sentence’ … I might even highlight it. ‘You know in this sentence up here? You don’t need a period there. You could use a semicolon.’ I’ll just throw in a little grammar instruction as we’re going along only if I think that they would be receptive to it.”

Mentor Texts: As the teacher and student go back and forth, students pick up on the teacher’s style of writing, and the teacher’s letters effectively become mentor texts. For example, when Galarza responds to her more advanced writers, “I might use a more complex sentence structure. I might combine sentences or use phrases and just more sophisticated language.” Often she notices students using these same structures in their own responses.

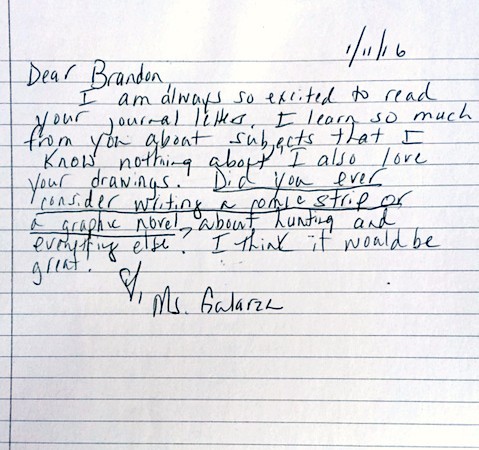

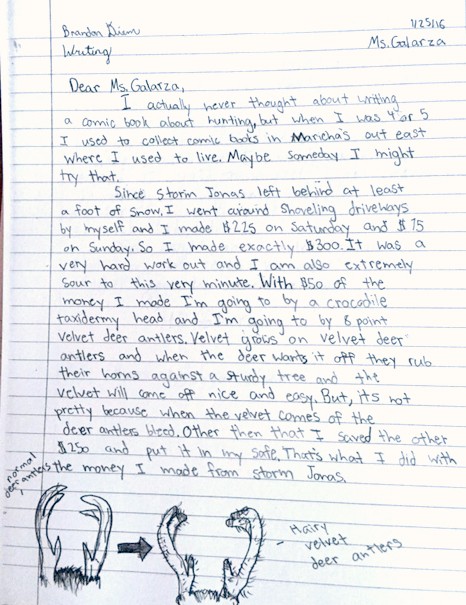

Funds of Knowledge: Keeping dialogue journals with students over time helps teachers discover students’ unique funds of knowledge, areas of expertise they might not have known about otherwise. “I had this student this year who was into taxidermy and hunting,” Galarza says. “I was so interested in it, so I asked him to give me information on it, and he really did. Like technical. Like it belongs in a book. And then he drew pictures.” She asked him if he ever thought about writing a comic book about hunting or taxidermy, and in his response, he considered it:

Relationships: Ultimately, the most important benefit of the journals is the relationships they build. When students feel they have a trusted adult in school, when they feel heard and seen, that makes school a place they want to come to.

“I don’t look at teaching the way many people do,” Galarza says. “I know that they could learn anything they need to learn from their homes with a device on their lap still in their pajamas. They don’t need me to learn. They need me to care.” ♦

Join the Cult of Pedagogy mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to my members-only library of free downloadable resources, including my e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading. If you are already a subscriber and want this resource, just check your most recent email for a link to the Members-Only Library—it’s in there!