The Fisheye Syndrome: Is Every Student Really Participating?

Greta just had an amazing discussion with her fifth period history class. They’ve been studying the Holocaust, and in today’s class, the points students brought up were so insightful. She had originally planned for about ten minutes of conversation, but things were going so well, she let it go for the whole period. Days like this make Greta feel like a great teacher.

Except for the stuff she didn’t notice. Like Haley. Haley had a lot of questions today, but never found the right moment to ask them. She doesn’t like to interrupt. A few times, she almost put her hand up, but someone else would start talking before she ever managed to lift it.

Robert is in that class too. He felt like an idiot the whole period—that one kid kept mentioning the Third Reich, and Robert wasn’t 100 percent sure what that was. He definitely didn’t want to ask.

Nadia thought the discussion was dumb—people really oversimplified the whole tragedy. But she didn’t want to start any trouble, so she said nothing.

And Becky and Kyle? The super shy ones? Naturally, they also stayed quiet. Oh, and three other students secretly texted the whole time. In fact, in Greta’s class of 28 students, only nine of them actually contributed to that discussion: Four of those were really into it, five commented once. The other nineteen just sat there. The whole time. Really.

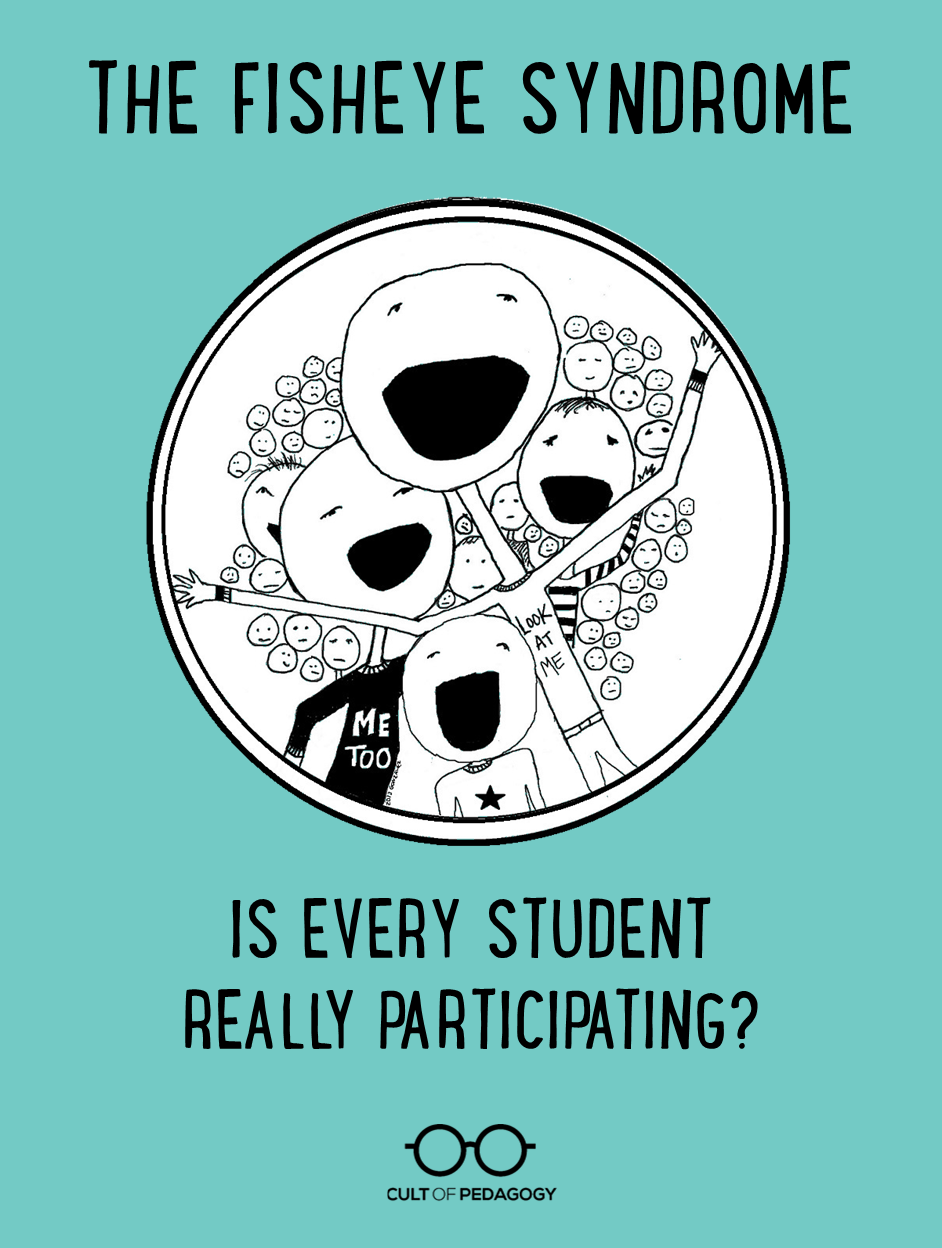

What Greta doesn’t realize is that she is suffering from the Fisheye Syndrome. It’s a condition that impacts our perception, as if we’re looking through a fisheye lens—the kind they use in peepholes. To those afflicted with fisheye, some students appear “larger” than others. They take up more energy and grab more of our attention, making the others fade into the periphery. We have a vague sense that the others are there, and we nag ourselves to include them, but those magnified students are just too hard to resist.

Not You!

Maybe you’re thinking this doesn’t apply to you, especially if you’re used to having animated debates with your students. Unlike some classrooms, where students are asleep most of the time, yours is interactive and engaging, right? Here’s the weird thing: The fact that your class seems so lively might actually be a stronger indication that you’re operating behind the fisheye lens.

I’ve been guilty of fisheye teaching. A lot. And I’ve seen many other teachers, good teachers, do it too.

I don’t think any of us do it on purpose. We do it out of habit, and because it’s so freakin’ gratifying: You pose a question, and one of your super talkative kids pipes up right away with an answer. It’s a good answer, one that takes the class in the direction you were hoping they’d go, demonstrating a solid grasp of the material. Wow, you think, they’re really learning! Then it happens with another student, another extrovert, and then one more. Things are hopping now, a bona fide “class” discussion, but really, you’re just volleying with three or four students. Most of the others have already checked out. We don’t realize it because we’re high on the whole thing, the nice rhythm we’ve got going with those three or four, that we lie to ourselves just a little.

If this sounds even the slightest bit familiar, do some investigating. The best way is to record a few of your classes on video. The only problem is, once you become aware of the imbalance in participation, you’re more likely to try and correct it while recording. Not necessarily a bad thing, unless you overcorrect during the recording and then go back to old habits, never recognizing the presence of the fisheye. Another diagnostic tool is a laminated seating chart: Using a dry-erase marker, put a mark in each student’s place on the chart every time he or she contributes to the class. In no time you’ll have a visual on who is talking and who isn’t.

Whether you think this is an issue in your teaching or not, my goal here is just to put the bug in your ear. To raise your awareness. Tomorrow, when you interact with your students, move your vision to the periphery and ask yourself if those students are as involved as they could be.

Why Equitable Participation Matters

Obviously, increasing student participation is a good thing. But apart from making school a more interesting place to be, why is it important to get all of our students involved in discussions? Can’t a student learn just as much from listening as they would from actively participating?

Discussion is a Pathway for Formative Assessment

Classroom discussion is one of the simplest, quickest, and most effective means of formative assessment we have. By asking our students good questions, we can determine what they know and how well they know it in seconds. But when we allow a pattern to emerge where only our most confident and verbally expressive kids respond, we miss the opportunity to assess the thinking of the others, and we may very well be fooling ourselves into thinking they’re all getting it, when really, they’re not.

Introverted Students Need Practice Speaking

Every year, the National Association of Colleges and Employers surveys employers about the skills they most want in potential employees (updated in 2016). In 2013, the ‘ability to verbally communicate with persons inside and outside the organization’ was near the top of the list. If our task is to help students become college- and career-ready, we are responsible for helping them grow as talkers.

All of our students—especially those who tend to stay quiet—will benefit from regular practice in presenting their ideas effectively, and no amount of listening compares to the cognitive and social challenge of actually having to frame your thoughts into coherent spoken sentences. Taking steps to ensure that all students have more opportunities to participate may be all that’s needed to nudge more introverted students to speak up. Low participation from others might be explained by cultural reasons, language barriers, learning differences, or neurodiversity. In these cases, accommodations may be needed to help students contribute fully.

Extroverted Students Need Practice Listening

Students who are used to center stage will benefit from letting someone else stand in the spotlight. In school, in their careers, and in their most important relationships, listening skills are hugely important. Chances are, your big talkers don’t have a lot of practice in skills like paraphrasing another person’s ideas, asking thoughtful follow-up questions, or thinking quietly before they speak. By making a concerted effort to balance the participation in our classes, we are giving those extroverts a chance to grow in ways that could have a powerful impact on their quality of life.

The End of Fisheye Teaching

So now that the lens is off, how to keep it off? How do we get more students involved? First of all, know that the goal is not to have all students participate at exactly the same rate; the push should be for more balance. If your quieter students contribute one good comment per discussion, that’s a step in the right direction.

Here are some ways to balance things out:

Make your intentions transparent. Talk to your students about this issue, and ask them to help change the current dynamic. This will prepare your less active students, so they won’t be startled by the sudden shift in attention. It will also help your extroverts understand why they are no longer getting the floor the way they’re used to. Some of this might happen behind the scenes: For those who frequently dominate the conversation, you might encourage them to limit the number of comments they make to three per class, or encourage them any time they paraphrase or build on another student’s comment or question. For those who typically hang back, have them choose a question ahead of time that they feel they could contribute something to, and plan to call on them for that item.

Increase wait time. Students vary in the amount of time they need to process higher-level questions. This need can be accomplished with extra wait time. We should be waiting at least three seconds between posing a question and calling on a student to answer (easier said than done). This gives everyone more time to think about what they want to say. Want to go even further? Add a “no hands” time, where no one gets to raise their hands at first: You ask the question, EVERYONE thinks for a moment about their answer with their hands down, then give them the go-ahead to raise their hands, then you call on someone. You’ll be surprised at what a difference this makes to the number of hands that go up.

Pre-load discussions. Give less talkative students a head start by slipping them the discussion questions ahead of time. Actually, go ahead and give them to everyone; all students would benefit from more thinking time.

Vary discussion formats. Any time you can give students a chance to share their thoughts with a smaller audience, you build their courage to share them with the larger group. This is where think-pair-share comes in handy: Rather than holding whole-class free-for-alls, put students in groups of two to four and pose questions one at a time, allowing each group to talk it over first, then call on representatives to recap their discussion for the whole class. Take this a step further by doing a think-WRITE-pair-share, where each student first considers their own answer, writes it down, then shares it with someone else. Not only does this give them more thinking time, it also forces them to answer the question on their own, rather than “what that guy said.”

Use icons. This strategy, described by Ruth Wickham, an English language teacher in Malaysia, is an ingenious way to get active participation from students in large classes. “I printed out four sets of little pictures, just clip-art type things, then I cut them up and stuck one on the first inside page of each (participant) workbook. The icons were all mixed up, so no one had the same as the person next to them, and there were four of each scattered around the room.” She then placed the same icons onto certain slides in her presentation. Whenever an icon (such as a duck) appeared on the screen, participants who had a duck on their paper had to come to the front of the room and answer a question or perform a task. “The looks on their faces every time they saw an icon appear was just classic! We all had a lot of fun and a lot of laughs even with such a big group.”

Finally, if your efforts to balance participation result in less activity overall, read When You Get Nothing But Crickets to explore ways to improve that situation.

Some students are naturally going to be more active, more talkative, livelier than others. We’re not trying to make them all be the same, just better, stronger, more balanced versions of the people that showed up on day one. With your little case of fisheye taken care of, you’ll be ready to help every one of them stretch closer to their full potential. That’s when the real conversation will begin. ♦

If you liked this one, come back for more. Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and joyful. When you join, you’ll have access to our Members-Only Library of free downloadable resources, including the e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half.