How We Pronounce Student Names, and Why it Matters

Listen to an Extended Version of this Post in a Podcast:

Samira Fejzic was used to people saying her name wrong, especially in school. “Through the years, as roll would be called, I would wait for that awkward pause—this is how I knew I was next. I accepted this ritual.”

Fejzic (FAY-zich), whose family left Bosnia in the early nineties and moved to the U.S. in 1999, experienced this ritual for ten years, and she understood that people in her new town weren’t used to names like hers, despite the fact that the area’s Bosnian population had grown massive in recent years.

“It never hurt me until high school graduation,” she recalls. “This was a big day for me. My grandparents from Bosnia came just to watch me get my diploma and of course, my name was butchered.”

If you’re in a position to say lots of student names—in your classroom, over the P.A. system, or especially at awards ceremonies and graduations—no one will be surprised if you mess up a couple of them. But this year, maybe you can do better. If you make the commitment now to get them all right, if you resolve this time to honor your students with clear, beautiful pronunciation of their full, given names, that, my friend, will be the loveliest surprise of all.

Three Kinds of Name-Sayin’

I grew up with a hard-to-pronounce name. Actually, it wasn’t that hard; it just looked different from what people were used to: Yurkosky. (Kind of rhymes with “Her pots ski,” minus the “t” in pots.) Year after year, it threw everyone off. And the way they approached the name put them into one of three camps: fumble-bumblers, arrogant manglers, and calibrators.

The fumble-bumblers I didn’t mind so much. They’d mispronounce the name, slowing down and making their voice all wobbly, not trusting themselves. They’d grimace, laugh, ask me how to say it, then try again. But then they sort of gave up. Over the next few attempts, they’d settle into something that was a kind of approximation, and that would be that. What made me not mind these people was that they put the mispronunciation on themselves—their demeanor suggested the fault was with them, not me or my name.

The arrogant manglers were another story. They assumed their pronunciation was correct and just plowed ahead, never bothering to check. In many cases, an arrogant mangler will persist with their own pronunciation even after they’ve been corrected. Adan (uh-DON) Deeb, whose family hails from Israel with Palestinian roots, experienced this as a middle school student in the U.S. “Every time I was called up to the office, EVERY SINGLE TIME, they would mispronounce my name, no matter how many times I corrected them. It made me angry. To me that shows that they just don’t care enough to get my name right.”

This group has a couple of sub-categories: One is the nicknamers—people who come across a name like Rajendrani and announce, “We’ll just call you Amy.” The other is the worst kind, the people who start with the first syllable, then wave the rest of the name away like so much cigarette smoke, adding “Whatever your name is,” or just “whatever.” I don’t have a creative name for this group. Let’s just call them assholes.

Finally, there was a small group I think of as the calibrators, people who recognized that my name required a little more effort. They asked me to pronounce it, tried to replicate it, then fine-tuned it a few more times against my own pronunciation. Some of them would even check back later to make sure they still had it.

My cousin Laura, who has the same last name I grew up with, remembers a professor who was a true calibrator. “It did take him a bit of time to learn to pronounce my name, but he was always apologetic when he said it wrong, and always insisted on the importance of getting such things right. He was easily the most inspirational and challenging teacher I’ve had…he just insisted that every student feel important.”

If you’re already a calibrator, keep up the good work. If you’re not—if you’ve let yourself off the hook with some idea like “I’m terrible with names”—know that it’s not too late to turn things around, and it does matter. Though it may seem inconsequential to you, the way you handle names has deeper implications than you might realize.

Kind of a Big Deal

People’s reaction to this issue varies depending on their personality. If your student has a strong desire to please, wants desperately to fit in, or is generally conflict-avoidant, they may never tell you you’re saying their name wrong. For those students, it might matter a lot, but they’d never say so. And other kids are just more laid-back in general. But for many students, the way you say their name conveys a more significant message.

Name mispronunciation – especially the kind committed by the arrogant manglers—actually falls into a larger category of behaviors called microaggressions, defined by researchers at Columbia University’s Teachers College as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (Sue et al., 2007).

In other words, mutilating someone’s name is a tiny act of bigotry. Whether you intend to or not, what you’re communicating is this: Your name is different. Foreign. Weird. It’s not worth my time to get it right. Although most of your students may not know the word microaggression, they’re probably familiar with that vague feeling of marginalization, the message that everyone else is “normal,” and they are not.

In her piece What’s in a Name? Kind of a Lot, writer Tracy Clayton (under the name Brokey McPoverty) rails against Ryan Seacrest’s move to shorten the name of actress Quvenzhané Wallis to “Little Q.” She points out that Seacrest and other media figures treat the names of some actors—who happen to be white—differently: “The problem is that white Hollywood…doesn’t deem her as important as, say, Renee Zellweger, or Zach Galifianakis, or Arnold Schwarzenegger, all of whom have names that are difficult to pronounce—but they manage. The message sent is this: You, young, black, female child, are not worth the time and energy it will take me to learn to spell and pronounce your name.”

This, by the way, is how you say Quvenzhané:

This issue goes beyond names rooted in cultures unfamiliar to the speaker. Whatever it is your student prefers to be called, it’s worth the effort to get it right. I’m sure I’ve not only mispronounced my own students’ names, but I’ve probably also called them something that was not their preference—realizing in April that the kid I’ve been calling Stephan all year actually prefers to be called Jude.

And before you get all defensive about the bigotry thing, let’s be clear: Discovering that something you do might be construed as bigotry doesn’t mean anyone is calling you a bigot. It’s just an opportunity to grow. An opportunity to understand that doing something a little differently shows others that you respect them. At some point in your life, someone probably taught you to hold the door open for the person coming in behind you. Before then, maybe you didn’t know. Opportunity to grow. It’s that simple.

How to Get it Right

The best way to get students’ names right is to just ask them. Pull the kid aside and say, You know what? I think I’ve been messing up your name all year, and I’m sorry. Now that graduation is coming, I want to say it perfectly. Can you teach me?

By humbling yourself in this way, you let them see that you’re human. You’re modeling what it looks like to be a lifelong learner, a flexible, confident person who is not afraid to admit a mistake. Regardless of the outcome, a genuine effort on your part will mean so much, and when the big day comes, they might even root for you to get it right.

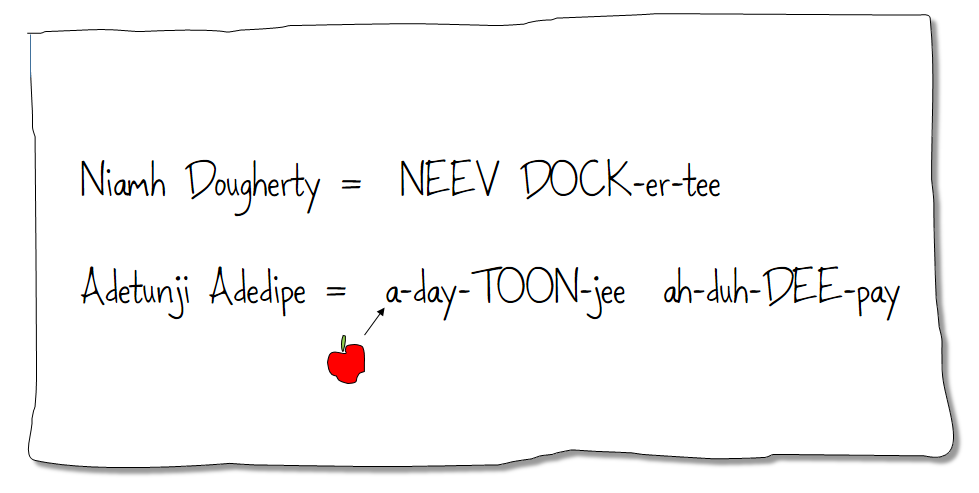

If you have hundreds of names to learn, get systematic: Starting now, carry around a clipboard with all the names you’ll need to say – even those you think you already know, and start checking in with kids in the cafeteria, in the halls, in the stands at a basketball game. And for God’s sake, write down what they tell you. When the big day comes, the page of names you read from should look something like this:

Do whatever it takes, using whatever kind of symbols or notes you need to get the right syllables out in the right order. (The apple is there to remind the speaker to say that “a” like they would in the word apple.)

If you’ve run out of time to ask students themselves, or if doing that is too uncomfortable for you, you can get some help online. On Pronounce Names, you can find a huge collection of names and their pronunciations.

Whatever you do, do something. For some students, you may be the first person who ever bothered. If the only time you say their name is in the classroom, your correct pronunciation will help the whole class learn it, too. Eventually that will ripple through the school, making that student feel known in a place where before they felt unknown.

And if you have the honor of announcing them on the day they receive their award, their diploma, the day that marks some big achievement, you have a unique opportunity to make it even more special, but you only have two seconds: Make it count. It’s a gift they’ll remember for a long time. ♥

Reference:

Sue, D.W., Capodilupo, C.M., Torino, G.C., Bucceri, J.M., Holder, A.M.B., Nadal, K.L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62 (4), 271-286.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration — in quick, bite-sized packages — all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. To thank you, you’ll get a free copy of my new e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half.