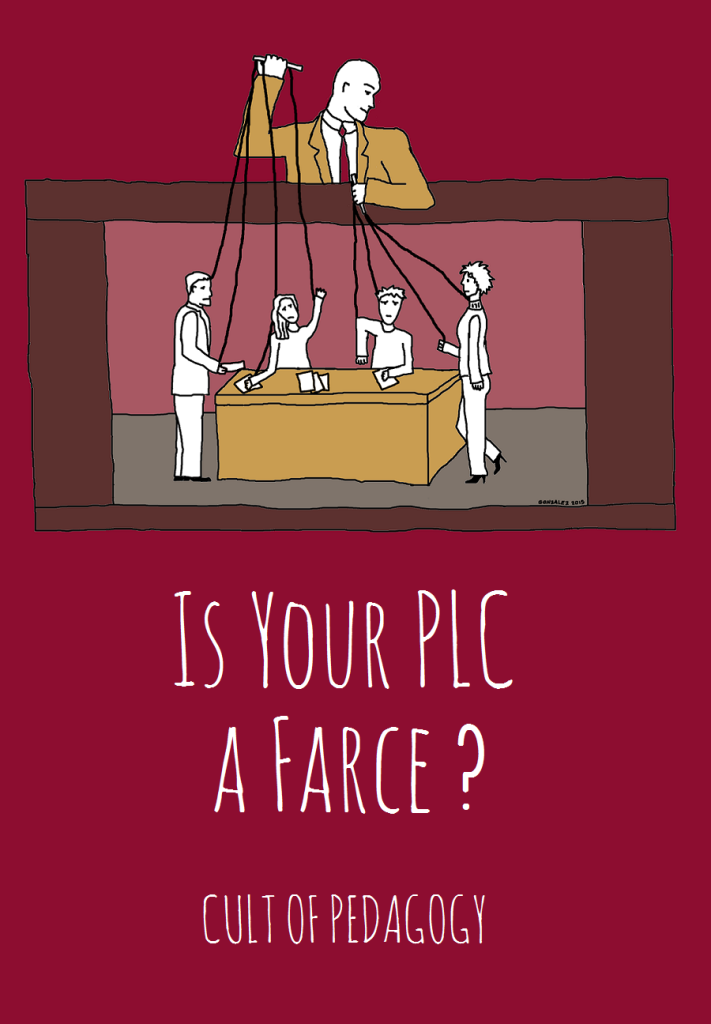

Is Your Professional Learning Community a Farce?

Many schools now use Professional Learning Communities for teacher collaboration, but whether they all truly fit that description is up for debate.

This week’s post was written by Chase Mielke. the teacher behind the video What Students Really Need to Hear.

Let’s play a game. It’s called EduLingo Bingo. It’s simple: Before a staff meeting or PD, make a blank bingo chart. Then fill in the blanks with words you predict your admin or the presenter will say. Keep it on the down-low, though, if you want to keep your job.

I recommend words like:

- RTI

- growth

- rigor

- differentiation

- Common Core

- college readiness

- bell-to-bell

- technology/1-to-1/flipped classroom

- student-centered

- and my personal favorite, PLC

There’s a reason I like EduLingo Bingo: It brings forward the idea that sometimes we use a concept to the point of abuse, hearing it twisted and turned so often that it no longer holds meaning and relevance. No place do I see this more than the concept of “Professional Learning Communities,” which are usually not: A) led by the professionals, B) full of learning, or C) run as communities.

As someone who has suffered pseudo-PLCs for years, it’s time I voice my frustrations, as well as offer suggestions for administrators on how to get the best out of their teachers and, in turn, the best out of their schools. In doing so, I hope to not only express my own discontent, but the discontent of thousands of teachers across the nation.

1. It’s not a PLC if we have no control.

The bastardization of true PLCs is occurring because teacher voice is often removed from the community. To put it in classroom terms, too many administrators treat PLCs more as homework than project-based learning. If you want us to simply do your bidding, call it a committee, not a PLC.

I can’t express the frustration I feel when our department aligns on something we truly think is affecting our students, only to hear, “No, we need you to focus your time on X” (where X = crash course diet approach to fixing a test score “crisis”).

Instead, trust us. Ask us what we think—what we know—will enhance student learning. You may be surprised how much we understand our own challenges. You may be surprised how much we naturally use data to support our beliefs. If we can’t agree on one thing, then yes, we may need some guidance. But let our passions, our talents, our expertise drive the process. “Trust” doesn’t mean you have to ignore our progress or avoid checking in. It means that we are talented professionals who know how to find, learn, and share worthwhile resources. We just need the freedom and time to do so.

To really provide freedom, ask us questions rather than giving us demands. Notice these two examples:

A) “You’ve said often that your curriculum maps aren’t always aligned. What would you need to align them?”

The above question tells us a few things: You have been listening to our frustrations, you care about our viewpoints, you recognize that we need resources, and you trust us.

Now look at this one:

B) “I noticed that your curriculum maps aren’t aligned. I’d like you to spend your PLC time aligning them.”

The second example leads us to think you may be helicoptering (and judging) our teaching, you are controlling our time, our needs and views are not as valuable as your needs and views, and we must do what you asked—you weren’t fooling anyone with that dainty “I’d like you to.”

One of THE most powerful things you can do for a PLC—for your teachers’ motivation—is ask us questions. Ask us what we need. Ask us how. Ask us why. And then set us loose.

2. It’s not a PLC just because we are reading the same book.

I get it. I read a book that I LOVE and think: “This is so great EVERYONE and his or her 8th cousin needs to read it!” But in my classroom, I shouldn’t subject kids to required reading just because I love it (otherwise my kids would be reading a LOT about neuroscience). I must consider my students’ needs, interests, and abilities first.

The same is true of PLC group reading. If you assign me something that is irrelevant or impractical, I will do what many students do: skim it just enough to make sure I can survive. It’s not that I’m closed minded; it’s that I have SO many readings in which I already find passion and purpose.

We are teachers because we love learning. We already have an unfathomable amount of books we’d like to read that would help us. And ten teachers reading the same book will not be nearly as fruitful as ten teachers reading different books on a similar topic. Ask us what we want to read—what we have already read—and allow us to synthesize the details. It’s what we do already, so give us the opportunity, time, and freedom to do it more effectively.

3. It’s not a PLC just because we are sitting together in a group.

There’s a myth that, if you place people into a group, they will automatically function well as a group. But you’ve been in a classroom that doesn’t have rules and structure. So don’t assume that a group will become high-performing simply because it consists of multiple people sharing a space. Real communities have norms, agreements, and rules. Some are unspoken and unwritten (e.g., I shouldn’t pee in my neighbor’s back yard). Others are written (e.g., It’s a law that I can’t light up the ‘hood with fireworks at 2 a.m.). We need both. We need agreements about our expectations and we need rules to hold us accountable.

We can create these guidelines ourselves after some clear modeling.

Please note: We shouldn’t spend more time talking about agreements and rules than we do actually learning.

Please note further: Writing them down and hanging them on the wall doesn’t mean we are using them.

Empower us to check in often about the community and to make our own adjustments as needed.

4. It’s not a PLC just because we are talking about standards or test scores.

My personal pet peeve. Yes, we understand why test scores matter. Yes, we understand the importance of using data to drive instruction (and trust us, we already do this). But when you assign us test scores to “unpack” it feels like you are saying, “Hey, I don’t have time to do this, so will you do it for me?”

And the summative data we get from state tests often isn’t as helpful as the formative data we are collecting daily. I already know that my students are struggling with “making textual inferences on persuasive nonfiction.” I don’t need the one SAT question on standard R3.52.9-10.C3PO to tell me what’s wrong. I need my colleagues to help me find solutions to fix it.

We understand that state test scores have a far-reaching impact on our enrollment, our reputation, and our jobs. But in the process of “chasing” summative tests (many of which drastically change each year), we lose our focus on what matters. So think more formatively than summatively. Let us focus on our formative data to enhance quality student learning, not quality student testing.

5. It’s not a PLC if we never act.

PLCs are like a group scientific process, and the scientific process doesn’t work without an actual experiment. So much of our PLC time is spent talking about trying things rather than actually trying them. Give us the freedom, the opportunity, and most of all the safety to try new strategies we’ve discussed in our PLC. It’s been said before, “Students take risks when teachers take risks. Teachers take risks when administrators take risks.” Are you willing to risk with us?

So remember, we don’t always need a new book, a state-test data analysis, or a fancy packaged program to improve our abilities. We need time. We need trust. We need to be treated as professionals. If you do these three things, BINGO! You will have professionals engaged in learning through a supportive community: a true PLC. ♦

Join the Cult of Pedagogy mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration — in quick, bite-sized packages — all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. To thank you, you’ll get a free copy of my new e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half.