Black Girls and School: We Can Do Better

Listen to my interview with Monique Morris, author of Pushout (transcript):

I want to tell you about Danielle. About halfway through my second year of teaching, the other teachers started talking about how Danielle Robinson was coming back. A seventh grade student, transferring over from another school. She’d start on Monday, they said. They sounded like they were talking about the weather guy predicting the worst tornado in decades.

As it turned out, Danielle was kind of legendary. She’d been at our school before, and seventh grade was more of an estimate of her grade, since she’d been absent so many times and held back at least once. Over lunch, my colleagues filled me in about her: the fights, the backtalk, the low-cut shirts, the constant truancy, the hickeys, the fights, the fights, the fights.

“Of course she’s getting sent back to us,” one of them said. “I heard she met her match at her last school and got her ass beat.”

The look on their faces, hearing this news, could only be described with one word: satisfied.

She wasn’t in my class that year, but I knew exactly who she was. You felt her coming down the hall before you saw her, because had a way of drawing a crowd. She’d shout insults and directives at the people she passed. When the bell rang, sending others scurrying to class, Danielle continued on as before, totally unaffected.

She was a force of nature, and to tell the truth, she scared me.

The following year, when I agreed to sponsor the student government, Danielle ran for student body president. The teachers had a complete fit. They scrambled, trying to figure out ways to stop her, but it was the beginning of the school year, a fresh start. She hadn’t done anything wrong yet, so they had to let her run.

She won.

Actually, there’s more to that story: The afternoon when I sat in my team room, counting votes, my mentor stopped by to see how the results were going. When I told him it was looking like Danielle would beat the other candidate, a white girl with straight A’s beloved by all the teachers, who had created a beautiful set of campaign posters, who would no doubt work incredibly hard in the position and do an excellent job, he told me this: It would be in my best interest to make sure the other girl won. I froze for a moment, not quite sure I understood his meaning. I asked for clarification, and he clarified: I should lie.

Thirty minutes later, I got on the school PA system and announced that Danielle would be our president that year.

Although I’d hoped to prove my colleague wrong, that Danielle would surprise everyone and turn out to be an outstanding student leader, that didn’t happen. I imagined myself mentoring her, developing her skills and strengths and showing everyone they were wrong about her. But I really didn’t know how. She made me nervous.

Her term as president started out okay: She attended the meetings and participated in the activities, but once the school year really kicked in, the absences started, then she got into a fight or two, and her grades were terrible. By February, according to school policy for extracurricular activities, she had to step down from her presidency.

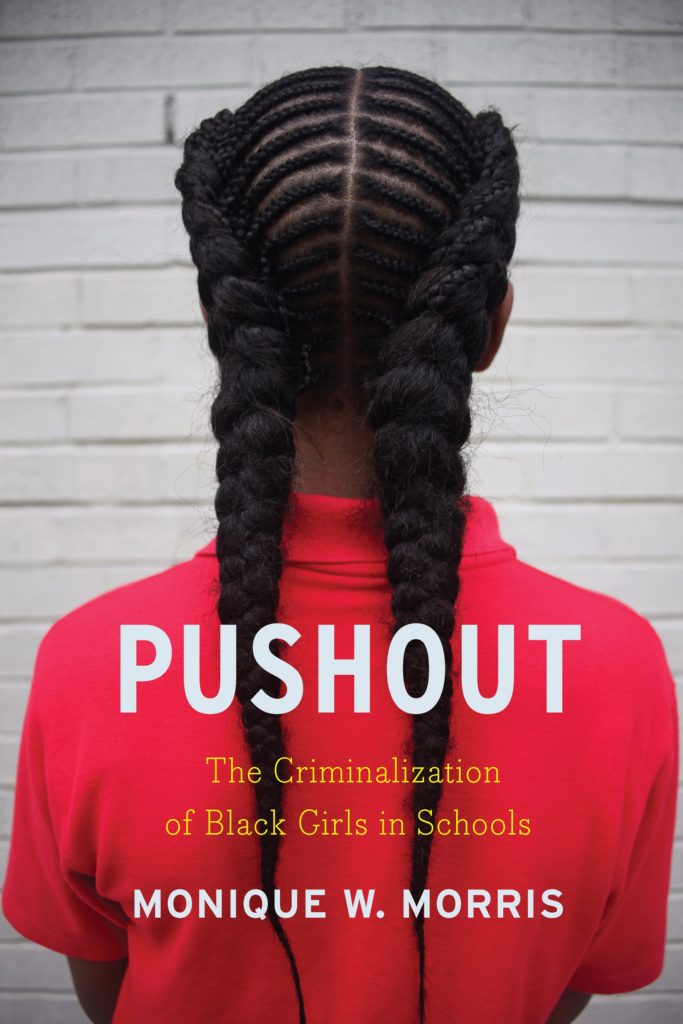

It’s my experiences with students like Danielle, my failures with the black female students in my own past, that made me take an immediate interest in the book Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools by Monique Morris, and it’s why I chose it for this year’s Cult of Pedagogy Summer Book Study. In the book, Morris examines the ways in which schools interact with black girls, the ways in which they are often criminalized when their behavior is treated as “delinquent,” and how our exclusionary responses to this behavior—usually through suspensions or expulsions—ultimately push many black girls out of school and into lives of abuse, sex trafficking, drug use, and various forms of incarceration.

For some teachers, especially white teachers, an examination of this dynamic might be overwhelming: We do our best with what we are given, some might say. If a child does not come to school ready to learn, there’s nothing we can do.

I disagree. I believe that a core responsibility of teachers is to meet each child where she is and help her grow. If a child does not come to school ready to learn, then our professional duty is to get her ready. And the only way to do that is to become very clear on exactly what each child needs. In this case, Monique Morris helps us better understand the needs of Black girls.

“Schools serve a greater social function than simply developing the rote skills of children and adolescents,” she writes. “As Black girls become adolescents, the influence of schools is critical to their socialization. This is especially important given that schools often serve as surrogates for influences that might otherwise be lacking in the lives of economically and socially marginalized children.”

If you work with students of color, and especially if your student population includes Black girls, you should consider this book to be required reading. It will deepen your understanding of what it means to truly meet the needs of these students, what mistakes you may have taken in the past, and specific steps you can take to do better. This could be especially helpful if you are not a person of color.

Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools

by Monique Morris

256 pages, The New Press, March 2016

My Personal Takeaways

Here are the points from the book that resonated most with me:

We need alternatives to exclusionary punishments.

Removing a student from class or from school through suspension or expulsion does nothing to change that student’s behavior, and because it detaches that student from the school culture and puts them further behind academically, it often makes the problem at the root of the behavior worse. Suspension is the default setting for certain infractions in so many schools, so I’m sure it’s hard to imagine what else could take its place, especially when so many schools proudly enforce zero-tolerance policies. “Zero-tolerance policies, while intended initially to keep communities safe,” Morris says in our interview, “really turned into a way for us to justify harsh hyper-punitive reactions to normal adolescent behavior.” Schools who really want to see their students’ behavior improve, rather than just removing those who misbehave, would be wise to learn more about restorative practices or programs like PBIS.

We need to build cultural competence.

We need to educate ourselves more thoroughly about our students’ backgrounds and cultures in order to more accurately interpret their behavior. By “cultural competence,” Morris is not referring to cultures from other countries. We have multiple cultures coexisting right here in the U.S., students whose home lives and cultures are quite different from what we typically expect in schools. In my interview with her, Morris describes an incident where a girl could be suspended for wearing a hat, even if she’s wearing it to cover a half-completed set of braids. “The request for her to remove the hat is actually culturally incompetent. For black girls, the two day process to braid her hair is actually less important – it was more important that she arrived at school for the test. It was more important that she was there in school to learn, than whether or not she had a hat hiding the fact that the top of her hair was not done.” If we as educators have a more thorough understanding of our students’ cultural backgrounds, we are less likely to interpret certain behaviors as defiant or problematic.

Co-construction of school rules is essential.

When teachers are the ones who define all the rules and expectations, we get less buy-in from students. One of most important ways we can improve our relationships with students is to co-construct classroom norms, to work with students to define expectations and how we will hold them accountable. In our interview, Morris explains why this works: “If educators are really focused from day one on helping their students and working with the students to co-construct what they need in the classroom to be present, and how they are going to work together around systems of accountability…when you work with kids to develop those agreements, they are more likely to be accountable to them.”

We must see ALL of our students as children.

One of the most significant shifts a teacher can make to better meet the needs of black female students is to remember that they are children. “There is this way in which we sort of cast children who are most at risk of getting in contact with the criminal and juvenile legal system as being different kinds of kids,” Morris says. “I don’t believe that. I don’t believe they are different. I believe that their experiences have been different and that has shaped their reactions to many things. They are not little women, they are children. They are developing, just like your child is developing. It’s really about leading with love.”

I have no idea where Danielle is now, but she should be in her early thirties. I pray that life has turned out well for her, but I suspect it hasn’t. I may not have contributed directly to Danielle’s pushout, but I certainly didn’t do anything to prevent it.

If I had read a book like Pushout when I was working with her, I know I would have done things differently. For one, I wouldn’t have been as intimidated. I would have seen her as a child who needed guidance and patience. I also would have tried harder: I didn’t understand the long-term consequences of her relationship with school. Most importantly, I would have asked my colleagues to read it.

And now, that’s the best thing I can do: Encourage you and the other teachers you work with to read Pushout with an open heart. I can’t wait to talk about this phenomenal book with you. In the comments below, share your own reflections on this book. Dr. Morris has agreed to join us, so if you have a question for her, include that as well. ♥

Join the Cult of Pedagogy mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to my members-only library of free downloadable resources, including my e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading!