Why is my kid allowed to make spelling mistakes?

Dear Cult of Pedagogy,

Last week, my son brought home a stack of papers from his first-grade class. Some of them had obvious spelling errors, but no one had marked them wrong. Later that same day, I was helping my 10-year-old daughter with a research paper. I noticed a few misspellings on her draft, but when I pointed them out, she said, “My teacher told us not to worry about spelling when we’re drafting.”

What’s the deal? Why don’t teachers seem to care about spelling anymore?

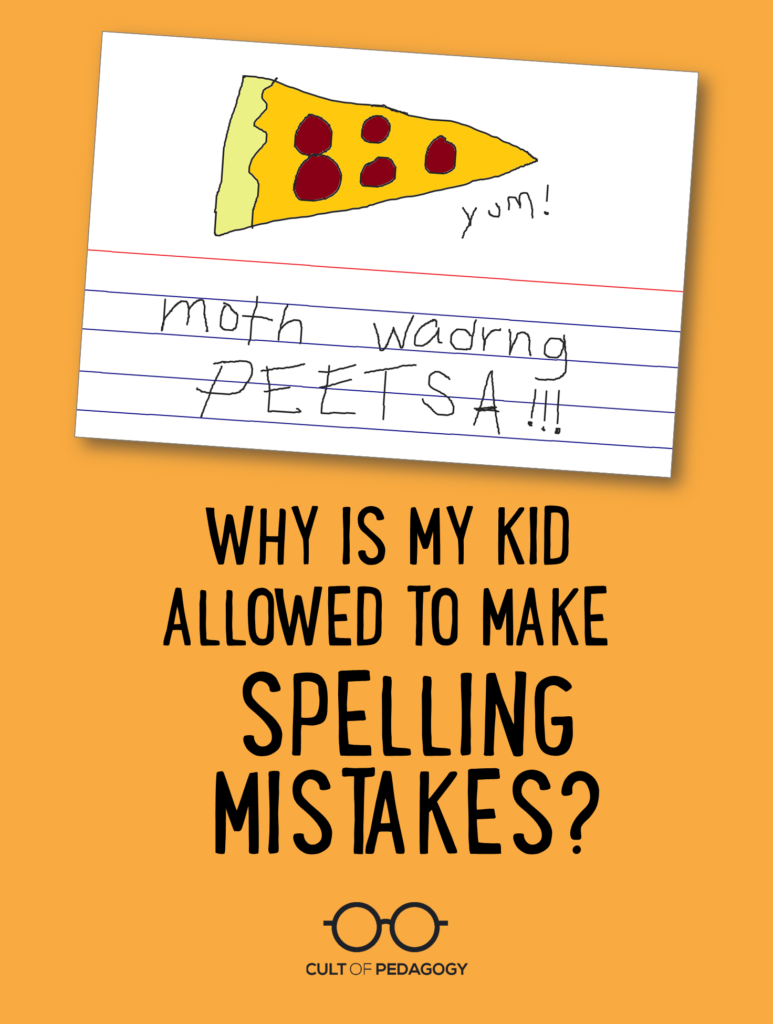

When kids first learn how to write, they grapple with many different skills at once. After they master letters and build them into words, their next step is stringing those words together into complete ideas. That takes a lot of mental work, and trying to spell every word perfectly can slow the whole process way down. For this reason, many teachers in the early grades encourage inventive spelling, also known as temporary spelling — where the child makes his best guess on the spelling of the word, rather than stopping to find out the correct version.

This practice is grounded in research. A number of studies demonstrate that kids who are allowed to use inventive spelling learn to write more quickly, more fluently, and with a richer vocabulary than those who work under more rigid spelling expectations (Kolodziej & Columba, 2005).

Researchers suggest that parents think about inventive spelling the way they once viewed their child’s early attempts at speech:

When the child said “ba-ba,” did the parent say, “No, honey, it is pronounced “bottle”? Parents treasure this developmental step their child took towards conventional speaking by lavishly praising the child and offering the bottle…The child will not call the item a “ba-ba” for the rest of his/her life; rather, when the child is developmentally ready, he/she will be able to say “bottle” (Kolodziej & Columba, 2005, p. 217).

In the later years, spelling does “count,” but it has a time and a place. Most writing teachers use some version of the Writing Process, where students are taught to (1) gather and group their ideas (pre-writing), (2) flesh out those ideas in sentences and paragraphs (drafting), and (3) reorganize the piece so that it accomplishes the writer’s goals (revising). Only then, after the piece has been revised into a shape that’s close to finished, do most teachers tell their students to start the next step: editing. In this stage, final corrections are made to spelling, punctuation, and usage.

The reason spelling and mechanics are de-emphasized in the first few steps is the same as in the younger grades: Too much focus on correctness interrupts the flow of ideas. Furthermore, teachers want students to understand that good writers revise their pieces many times for structure, development, clarity and voice. Although the mechanics are important for polish, correct spelling can’t make up for a poorly structured, underdeveloped piece of writing. And if a piece is going to be revised several times, it makes no sense to keep correcting the mechanics, only to have those words dumped entirely in a later revision.

Producing a finished piece of writing is a lot like putting on a polished musical performance: It requires the synthesis of many skills, some of which need to be handled separately. Imagine if a band conductor brought a brand-new piece of music to her band and expected all sections to play it together, perfectly, the first time. Even someone with no musical training can see that this is an unreasonable approach. Instead, if each instrument section starts by practicing their part separately, the performers will get really solid on their individual parts before pulling it all together to refine the complete performance.

So what should you do if your child comes home with a paper full of spelling or other mechanical errors? Take a cue from the teacher: If the teacher hasn’t mentioned the errors, then spelling was not a priority for this particular assignment or at this particular stage. Instead, praise the content itself. Here are some specific things to look for, and if they are there, to praise:

Strong, vivid vocabulary: “You chose a really interesting word to describe that monster – ferocious.”

Idea development: “You described how the lizard’s tongue works really clearly. At first I couldn’t understand how a tongue can smell, but this sentence helps.”

Audience awareness: “This introduction really grabbed my attention.”

Organization: “Nice transition here: ‘On the other hand.’ That’s a good way to show that you’re going to talk about a different side of the issue.”

Attempts at sophisticated construction: “Is that a semicolon? That’s a pretty advanced punctuation mark. I like to see you trying new things with your writing.”

If you want to help your child improve his spelling, keep assignments that contain errors in a folder. Later in the year, after a certain kind of word has been taught – say, the difference between there, their, and they’re — have your child go through the folder and see if they can catch some old mistakes with this set of words.

Rest assured, teachers still care very much about spelling. They just recognize that learning other skills — harder, more complex skills — often works best when those skills get a student’s full attention. Single instruments first, then the whole orchestra.

Reference:

Kolodziej, N.J., & Columba, L. (2005). Invented spelling: Guidelines for parents. Reading Improvement, 42 (4), 212-223.