What I Love About José Vilson’s “This Is Not a Test”

It used to be that our work as teachers was isolated. Even in large schools, we could only know a few other teachers well enough to know their most deeply held beliefs, to understand what went on in their heads as they dealt with the challenges of the job. So we could never be sure whether anyone else experienced teaching the way we did. But technology has changed all that. It has allowed us to connect with other like-minded people, people whose ideas and convictions help bolster and refine our own, who put the thoughts we can’t quite explain into words that are powerful, honest and brave.

People like José Vilson.

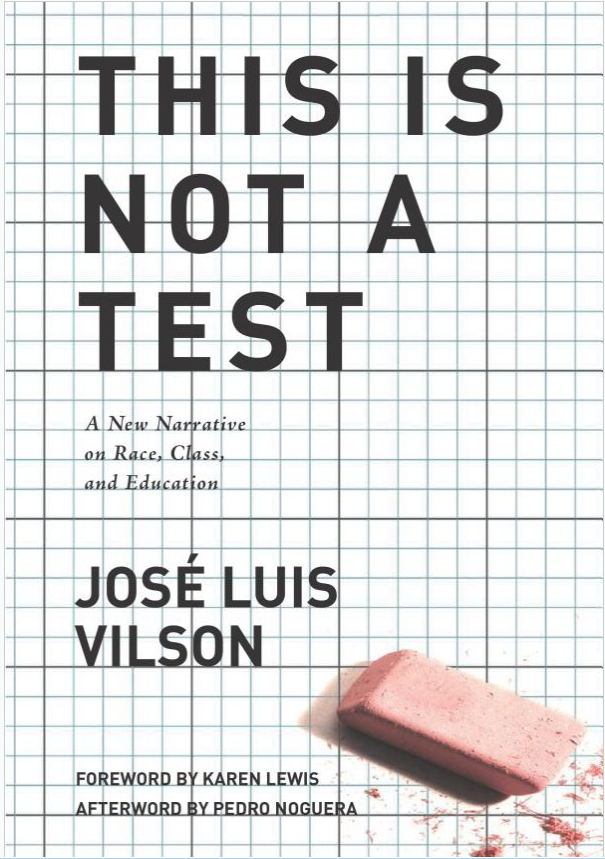

Vilson’s book, This Is Not a Test, is a collection of personal stories and passionate essays about his own education, his work as a teacher, and his journey from anonymous blogger to The José Vilson. It’s a good read, and an important contribution to the growing canon of texts that dissect U.S. education at this pivotal time in history.

Here’s what I loved about it:

Vilson’s voice is familiar. Reading This Is Not a Test didn’t feel like reading an “education” book. It wasn’t work. It was like talking to someone I know. His classroom stories remind me of my own, the kinds of stories teachers don’t often share out loud for fear of looking unprofessional. Like the way he handled one student’s highly inappropriate comment:

…he came up to me and said, “So Mr. Vilson, guess what?”

“Yes, Azzam?”

“I was doing your wife last night. She was really good.” The rest of the class laughed and stared at me, awaiting my reaction.

I furled my lower lip, nodding my head while everyone got their giggles in. Then I said:

“Funny you should say that, because I talked to my wife last night and she said you didn’t do her very well.”

“OHHHHHHH!” yelled the class.

Though this scene will raise eyebrows for some, I loved it. The world you create with your students — the one that belongs only to you and them — it’s like that. Sometimes you say things other teachers would disapprove of. Not every day, but you know when the time is right. The fact that Vilson gets this makes me think I would love to teach across the hall from him.

Another story I related to was about a teacher Vilson worked with, whose “obvious contempt for the kids” put Vilson in an awkward position, one I have found myself in more times than I would have liked. “The students became so in tune with that hate that they would run, scream, and shout to get into my classroom.” I had that same experience, and to know I was not the only one, and that someone else handled it in much the same way I did, is a comfort.

And there’s the cursing. Vilson doesn’t shy away from profanity, and for me, this is a plus. I always knew my love of the strategically placed swear word was motivated by more than immaturity or laziness, but it was only when I read Vilson’s defense of the practice that I had a clear explanation for it: “Cursing isn’t just a way to vent. It serves a purpose: to shock the usually puritan education audiences and aggressively advance ideas about the need for change.” Thanks for that one, José. I have a feeling I’ll be quoting you in the near future.

It’s kind of all over the place. There were times while reading when I thought, I can’t review this; it’s too hard to pinpoint what this book actually IS. The book doesn’t follow a straight narrative path; it doesn’t lay out a clear sequence of one-note essays; it doesn’t offer easily referenced pieces of advice. It does all of those things, all at once. The bad thing about this is that it’s hard to describe the book in an elevator pitch. The good thing is, the book has texture: It covers a LOT of ground and there is something for just about everyone. At one point, you’re reading about the hollowness of our obsession with ed tech. At another, Vilson’s rejected application from Teach for America. At another, the relevance of finding a rat in your bathtub when you’re five years old.

And that’s okay. Because education is messy. The psychology, the pedagogy, the policy and technology — it’s all tangled up together with socioeconomics and race and privilege. And each of us brings our own personal history into the mix. To edit out those complexities for the sake of uniformity and order would be to deny huge pieces of the puzzle. In the book’s introduction, Vilson addresses this: “I’ve been told that in order for my writing to be universal, it must turn away from things like race or nationality or the conditions of my upbringing. I can’t allow that. Too many others have felt as I felt, have seen what I saw, have wanted their personhood recognized and their rats counted.” If Vilson had tried too hard to make This Is Not a Test just one thing, it would be something far less than what it is.

It provides an entry point into the conversation about policy and reform. Most teachers are way too busy to discuss educational policy with full, informed confidence or, for that matter, even keep track of it. And books that provide a good overview (like Diane Ravitch’s Reign of Error), aren’t the kind of light reading you can do for a few minutes at a time in bed. But this book is readable. Vilson’s voice is accessible. It’s personal. And although the book isn’t strictly about policy and reform, it goes deep enough to give you a good idea of what’s been going on.

For education writers, it’s instructive and inspiring. I loved reading about Vilson’s experiences a blogger. He writes about developing a teacher voice, about claiming authority based on the sheer fact of having been in the trenches: “I first had to develop my own agency. I couldn’t wait for a corporate sponsor, a doctoral degree, or a person from on high to validate my hard-earned experiences….The most important reason to listen to teachers is that we see our students more than anyone else does.” That one meant a lot to me, because I have neither a doctoral degree nor a corporate sponsor, and I’m not sure I want either one. Vilson is many years ahead of me as a blogger, and I’ve learned a lot about the challenges of this occupation by reading his story.

It’s hopeful. Although Vilson has plenty of criticism about the current state of education in this country, and specifically, the misguided attempts to reform it, he is equally critical of those who do nothing but complain about it. “When sarcasm and vitriol are the only ways of discussing educational policy, we all lose.” He does not choose sides easily, which is something I appreciate, because things are not as clear cut as some would make them: It’s not as simple as “Reformers Bad. Teachers Good.” He digs into the nuances, acknowledges the complexities. And this makes his work rich and true.

I know I will come back to this book many times, to pull great quotes, to re-read sections that resonated with me. I know I will be a regular reader of Vilson’s blog, which gets better every time I go back to it.

And I’ll snatch up his next mic-dropping, truth-telling book as soon as it’s out. ♦

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Come on in!!