Listen to the interview with Connie Hamilton:

Sponsored by EVERFI and Verizon Innovative Learning HQ

This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

It’s pretty well known in educational circles that cooperative learning is supported by research, but so many teachers still struggle with it, so when things don’t work well, they give it up. In my observations of thousands of teachers, I’ve noticed that sometimes the smallest tweak in instructional approaches reaps the biggest impact, and group work is no exception.

I’ve gathered some of the most common efforts among teachers everywhere that aren’t met with the same amount of effort and success from their students, and for each one, I offer a small tweak that can make big improvements. Sometimes the tweak is a shift in semantics, other times it might be a slight change in how information is presented, and in some cases, it focuses on how teachers react when students lean on them to “help” instead of doing the heavy lifting themselves.

The instructional methods are sorted into six categories: grouping structures, giving directions, assigning roles, support during student collaboration, the teacher’s primary role, and the learning tasks. In each of these six categories, look for examples that describe how you approach or respond to group work, then consider these suggestions for elevating the effectiveness of student collaboration while limiting or reducing the energy you contribute.

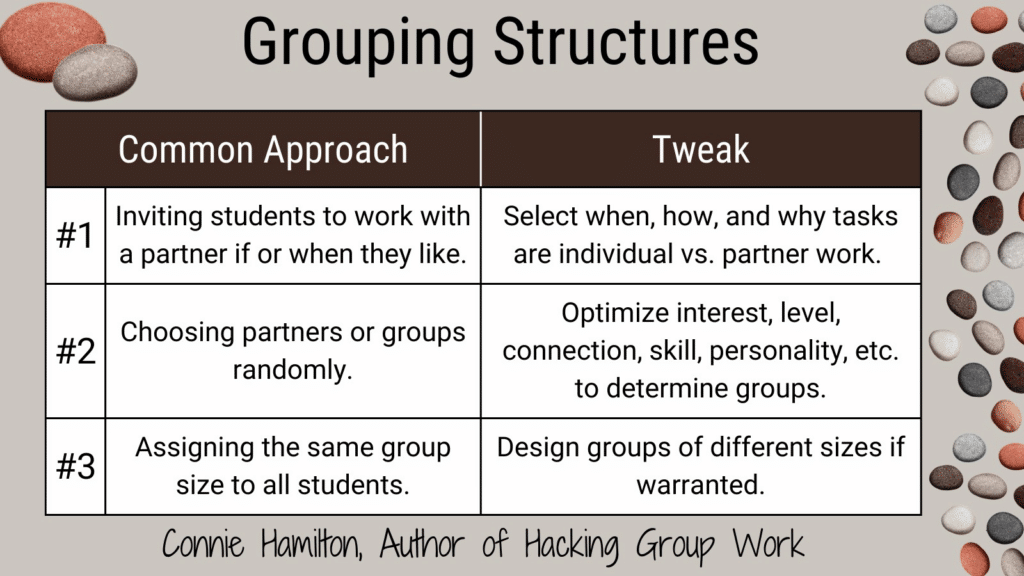

Grouping Structures

When determining how students will tackle a task, our options are to have students work independently, with a partner, or in a group. Be more intentional with how you make this key decision by considering some of the thoughtful decisions around structuring student work.

Common approach #1: Inviting students to work with a partner if or when they like

Tweak: Select when, how, and why tasks are individual vs. partner work.

While the goal for allowing students to work with a partner any time they choose is intended to send the message that we can always get help from peers, it doesn’t leave room for purposefully designing a task with collaboration in mind. The interactions between students is often not much more than a quick check to see if they got the same answer, rather than communicating their thinking along the way. So when you assign partner work, do it with intention.

Common approach #2: Choosing partners or groups randomly

Tweak: Optimize interest, level, connection, skill, personality, etc. to determine groups.

It’s OK to have random groupings once in a while, especially when a quick engagement strategy is needed. However, if groups are primarily student choice or random, we miss the opportunity to mindfully align students with others based on a variety of factors.

Try using Clock Partners to organize multiple pairings. Here’s how it works: Students make “appointments” with different peers at specific times. Then, when the teacher announces they should join their 3:00 partner, the pairings are already predetermined. Only you know that the 12 o’clock partner is a reading buddy, while the 6 o’clock partner considers how introverted or extraverted students are.

Common Approach #3: Assigning the same group size to all students

Tweak: Design groups of different sizes if warranted.

When flexibility is warranted, allow for a blend of solo, partner, and group structures. It can be effective to have groups of 4 or 5, a couple of partners, and a few students working alone. Depending on the task, you can offer varying levels of challenge based on their group structure.

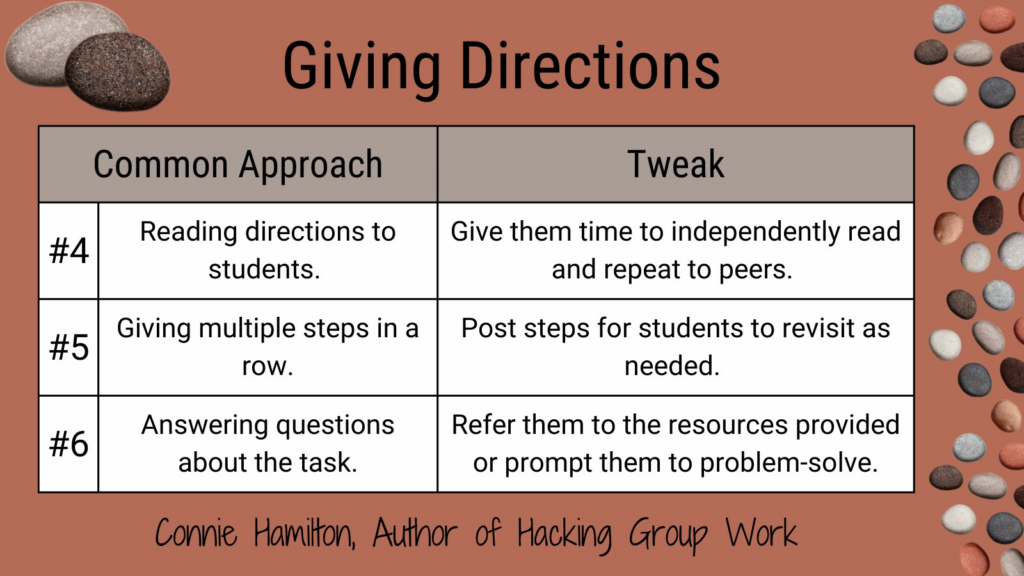

Giving Directions

How students engage in active learning usually has steps or at a minimum some guidance. Students come to expect teachers to be the beacon of information when it comes to describing exactly — and I mean every minute detail — of what they are supposed to do.

Common Approach #4: Reading directions to students

Tweak: Give them time to independently read and repeat to peers.

Instead of reading directions, or even having a single student read them to the entire class, give your learners time to read independently, then repeat or paraphrase them to a partner. If your students often disregard the directions, this small tweak will not only give them two exposures (once when they read and once when their partner repeats), but it also gives you a point of reference. You can easily refer them back to the directions if they are going rogue in a way that jeopardizes learning.

Common Approach #5: Giving multiple steps in a row

Tweak: Post steps for students to revisit as needed.

Working or short-term memory is taxed when multi-step directions are expected to be retained for future reference. Instead of requiring students to remember all the steps of a complex task, provide a visual with them clearly stated.

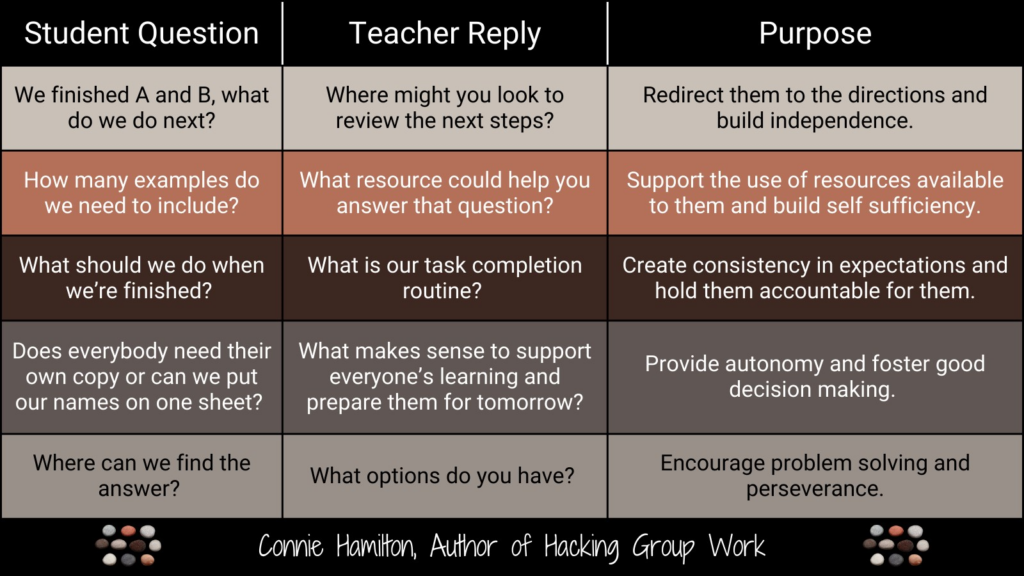

Common Approach #6: Answering questions about the task

Tweak: Refer them to the resources provided or prompt them to problem-solve.

When you have provided an opportunity for students to review the directions and have made them accessible for reference as needed, there’s no need for you to answer questions that they can clarify without asking you. Try to build independence and responsibility by encouraging students to access other sources to get the information they seek.

One way to accomplish this is to respond to their question with a question that prompts reflection or metacognition (see examples above). Answering questions with a question bounces the responsibility off of you and back on to them.

Of course, what you say is as important as how you say it. Cynical or sarcastic tones, when posing questions, can break down your relationship with students. Be sure your questions are delivered in a positive and productive way that strives to encourage students to activate their empowerment.

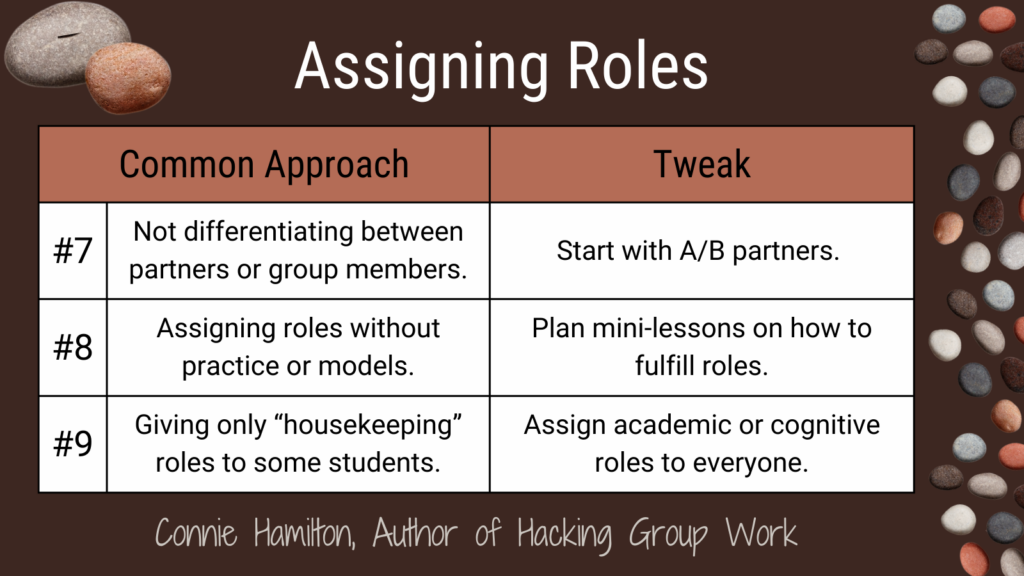

Assigning Roles

As adults who have ample opportunities to practice effective communication skills, it can be easy to overlook the fact that students do not always know how to balance partner or group tasks or communicate with peers. These are critical soft skills that can be fostered when collaborative tasks have structure and students understand the various roles group members or partners play when working and learning together.

Common Approach #7: Not differentiating between partners or group members

Tweak: Start with A/B partners.

The easiest way to elevate your intentionality and make student collaboration more effective is to assign names for your partners. A/B, red/gold, peanut butter/jelly, it doesn’t matter. This simple detail assigns a speaker and a listener and structures the conversation to ensure the speaker is heard and the listener understands. It’s the basics of the communication cycle where the sender (speaker) sends a message and the receiver (listener) provides feedback about the message.

Common Approach #8: Assigning roles without practice or models

Tweak: Plan mini-lessons on how to fulfill roles.

Don’t get overwhelmed by this tweak. Just start with one skill at a time. Offer a mini-lesson that clearly explains how a quality summarizer, questioner, or detective would perform their role. Include models that students can critique or reflect on their effectiveness. In a small group, assign one person to execute that role, then rotate it to another group member or partner for the second part of the task.

Eventually, you will have a list of roles like the ones above that students understand how to apply in their collaborative groups. The goal is for all students to have all the skills and be able to apply these soft skills fluidly without the need to be assigned a specific role.

Common Approach #9: Giving only “housekeeping” roles to some students

Tweak: Assign academic or cognitive roles to everyone.

Jobs like “materials manager” or “time keeper” might be necessary to support groups in their journey to successful learning, but students should not have the sole role of making sure everyone has a ruler and a pencil. Every learner should be assigned a cognitive role that contributes to the learning of the group and each individual in it. Then, if you want to assign housekeeping tasks, they are add-ons to the academic roles. So for example, your summarizer might also be responsible for returning supplies at the end of the lesson.

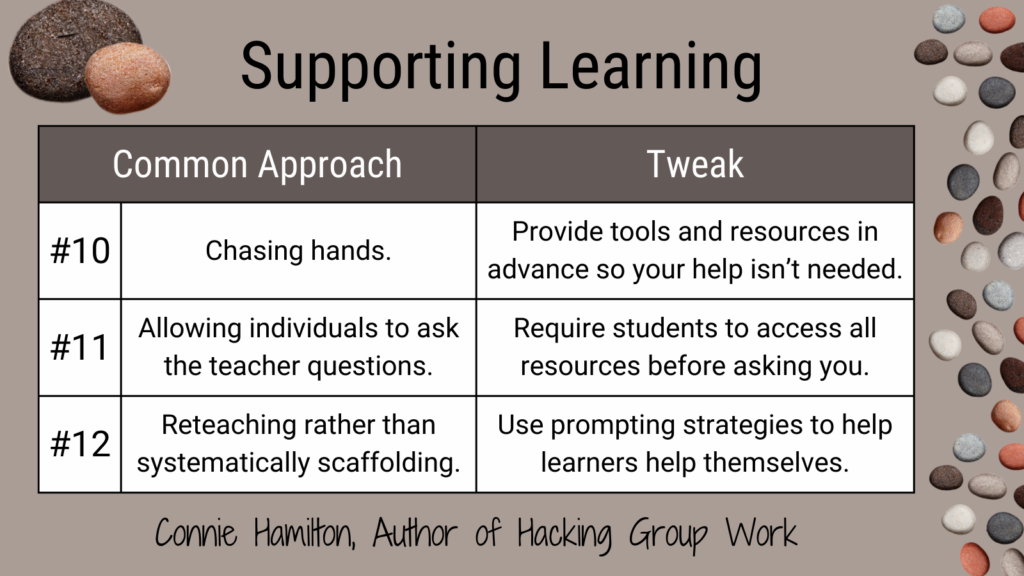

Supporting Learning

Facilitating effective group tasks is no easy feat. It requires careful thought and intentional planning. When you have gone through the time and effort to coordinate a quality collaborative learning task, resist the natural tendency to slip into a teacher-directed mode every time a student seeks your help.

Common Approach #10: Chasing hands

Tweak: Provide tools and resources in advance so your help isn’t needed.

During collaborative learning, the goal is for students to learn from and with one another — not you. Students already know you’re the safety net. Ideally, we provide other options — such as appropriate tools, access to a text, sufficient or additional time, and opportunity to collaborate — that help them persevere through productive struggle before asking you for help. So for goodness sake, don’t front load an invitation to seek you out at the first sign of difficulty by announcing, “If you need help, just raise your hand and I’ll come over.” Just think for a moment what this communicates and encourages.

Common Approach #11: Allowing individuals to ask the teacher questions

Tweak: Require students to access all resources, including other group members, before asking you.

When groups are truly working together, they tap into each other’s expertise, knowledge, and thoughts. If an individual partner or group member has a question, do some investigation to make sure the other group members have been included in problem-solving before you were sought out. A simple question such as, “What have you tried so far?” will initiate conversation about potential options and could lead to an “aha” moment without your help.

Common Approach #12: Reteaching rather than systematically scaffolding

Tweak: Use prompting strategies to help learners help themselves.

During lessons, teachers are constantly checking for understanding through structured or casual formative assessments. When a red flag comes up indicating that learners have misconceptions, are struggling, or simply haven’t met the target, it’s natural to have an urge to support them. Rather than revisit a lesson to reinforce a concept or skill, trigger problem-solving by giving metacognitive prompts. Before repeating the key points of a lesson, try asking questions like What strategy might work?, Where have you seen a similar problem?, or How are you going to tackle this? These types of questions trigger students to think about the knowledge they already have, then apply it. When you jump to reteaching, you skip the opportunity for students to lead their own success.

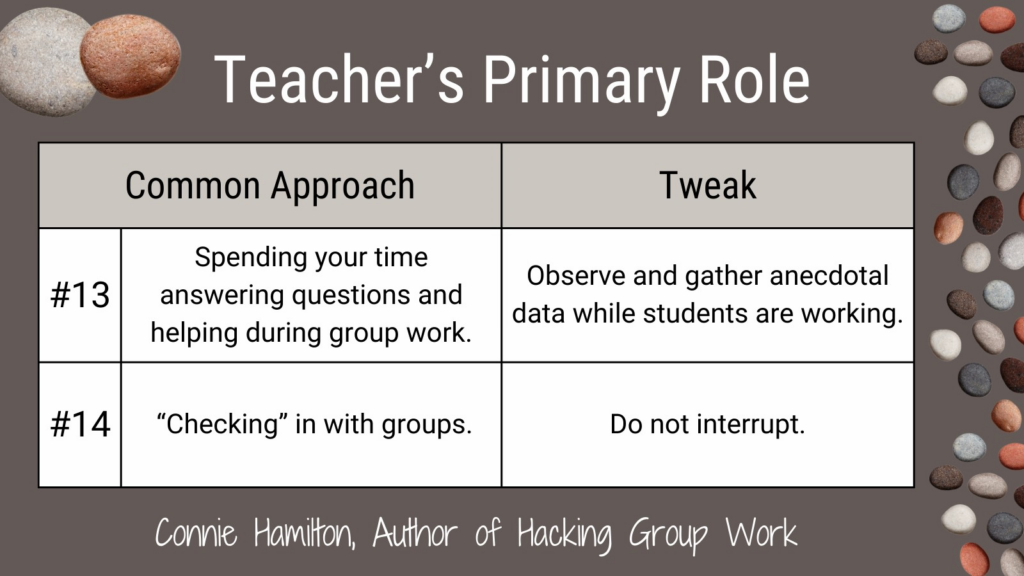

Teacher’s Primary Role

A collaborative learning structure positions students in the center of their learning. By design, the intent is for the teacher to take a passive role, seemingly invisible. It’s often our nature to uncloak too soon and flip the lesson to be more teacher-centered during small chunks of time without even realizing it.

Common Approach #13: Spending your time answering questions and helping during group work

Tweak: Observe and gather anecdotal data while students are working.

Your primary role is to listen and watch as students build their learning. This is sometimes a mindshift that is hard to make and even more challenging to maintain. Carry a clipboard or tablet to document what students are grasping, what is challenging, and who has provided evidence of learning. Not only will your noticings be valuable assessment data, but you will be more aware of when you are pulled away from your task to assist students in doing theirs.

Common Approach #14: “Checking” in with groups

Tweak: Do not interrupt.

The gradual release of responsibility (GRR) is often referred to by its “I do, We Do, You Do” parts. Every time you approach a group and ask them how it’s going, you effectively jolt them from the “You Do” part into the “We Do” phase of GRR. Unless you have a need to abruptly stop their learning progress and have them repeat what they’ve already done or learned, don’t. Stay invisible by listening from a short distance to hear and observe how students are doing rather than interrupting them.

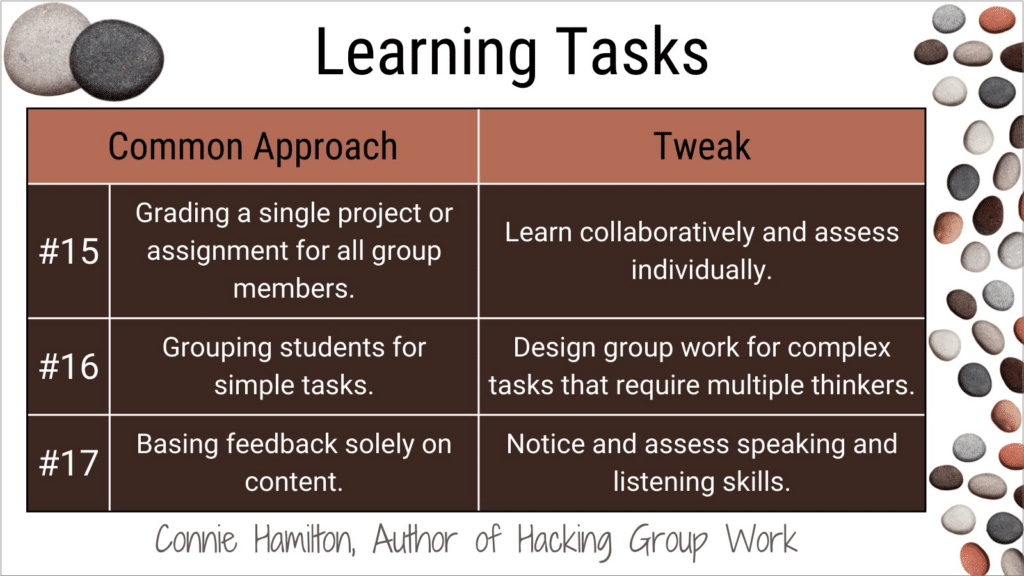

Learning Tasks

Learning targets, learning intentions, lesson objectives, or whatever you label as the purpose for the lesson, are almost always linked to content expectations. They communicate what students should know and be able to do in math, music, writing, and so on. When students have clarity on the learning target, it is much easier for them to work toward that goal. When teachers hold that level of clarity, instructional decisions during the lesson are intentional and therefore, more successful.

Common Approach #15: Grading a single project or assignment for all group members

Tweak: Learn collaboratively and assess individually.

I have been involved in countless conversations about group grading practices during collaborative learning. The research that supports collaborative learning applies to individual learners, not the group as a whole. The act of engaging with other learners while you’re learning not only deepens the learning, but makes it more likely for students to remember it. However, group grades do not reflect how each student stacks up against the target. Activities that involve groups working together should be followed by individual assessment to gather accurate data about what each student took away from their group learning task.

Common Approach #16: Grouping students for simple tasks

Tweak: Design group work for complex tasks that require multiple thinkers.

Just because there is evidence that group work and student collaboration supports learning, doesn’t mean it’s always the best fit for every lesson and learning task. When a planned activity is simple and students are capable of completing it independently, you run the risk they will devalue working with their peers, regardless of the task, because they believe they don’t need their peers. Select a collaborative structure when a variety of thoughts and ideas will benefit each individual’s learning. Remember, group or partner work is more than just sharing the load to complete a task. Collaboration should offer a perspective or experience that single students would not have without their classmates.

Common Approach #17: Basing feedback solely on content

Tweak: Notice and assess speaking and listening skills.

Soft skills like problem solving, respectful listening, patience, articulating thinking, and many more are qualities educators and families expect students to exhibit. But too often, we don’t necessarily give these skills attention unless they’re exceptional or lacking. Instead of isolating your feedback solely on what students learn within your content area, pick a speaking and listening skill and include comments about how it is helping or hindering their group’s effectiveness.

If you recognize one of these common approaches to group work in your own teaching style, give it a tweak and pay attention to the impact your subtle change makes on the effectiveness of group work.

Hacking Group Work is available on Amazon and Bookshop.org.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

This was an inspirational post and thank you for sharing. I really enjoyed reading new ideas and how to make group work for effective. I am excited to apply my new knowledge in the middle school classroom. My school building is looking to promote greater student engagement this year through different instructional strategies. I plan to share your idea of instead of reading directions to the group to have students silently read and share with a peer. I plan to share this blog with others.

Thanks, Kristen. Any updates with how it’s going?

This was a really helpful article. I’m currently in a teacher preparation program and seeing effective classroom management tips is extremely helpful as I traverse my student teaching. I especially appreciate the focus on group work effectiveness, since it’s a common learning strategy but no tips are given to boost student engagement. I also like how you mentioned not interrupting student work time. I think we’re frequently encouraged to “check in,” but I feel as if it sometimes throws off the students when I interrupt them. Thank you for the read! 🙂

Thanks for your comment. I’m glad you found some useful tips. Best of luck in your career.

Thank you for this very informative post. I agree that educators need to focus on either random groupings or intentional groupings to gain a positive sense of community in the classroom. When making intentional groups, we are able to organize students by their interests, skill levels, and leadership skills. I also agree that it is important to model how group collaboration should work and give clear expectations prior to implementing group work.

This was a very informative article, and I am delighted to have found it. I am a current middle school history teacher and many of my lessons are centered around collaborative learning. I have run into the problem where my students only want to work with peers they know and are friends with and I want my students to have the skills to work effectively with others they may not know. I find the strategy ‘ Clock Partners” so interesting and I am excited to implement this in my class.

Hi Alexandria -so glad this was helpful! Let us know how it goes!

There is a free “Clock Partner” template on the resources tab on my website if you’d like one that’s readymade.

Even after 18 years of teaching, it is so cool that I can find new ways to improve my lessons! Your article was extremely informative and I can now see that, while I think I have wonderful collaborative activities, I need to be more intentional with how I conduct them. I have a collaborative problem solving lesson coming up next week and I’m going back to do some revision based on your Group Work tweaks. Thank you so much!

Glad to hear the article gave you some good ideas, Christy! All the best!