Listen to the interview with Colin Seale:

Sponsored by Hapara and TGR EDU: Explore

This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

My son Oliver is enrolled in virtual school this year. He has an amazing teacher who kicked off the year with her kindergarten students by going through the alphabet. As they went through each letter, students had to suggest words that started with that letter.

When they got to the letter after H and before J, one student yelled out, “Iguana.”

“Great work!” the teacher said. “Who else has a word that starts with our letter?”

Crickets. No one said anything. As an eavesdropping dad, I was thankful this wasn’t a drinking game, because I had nothing! Suddenly, Oliver unmuted, huge smile on his face, and joyfully shared his answer:

“Lizard!”

His teacher looked at him, smiled, and said, “I’m sorry, that’s not right. Does anyone else have a word that works?”

I looked at him and saw the joy stripped from his eyes. I started to think about the wonder he and just about every child comes out of the womb with. I began to worry about what happens when we stifle that wonder because of our rigid practice of creating such a narrow window of what we consider to be helpful contributions. And I fully understood how it comes to be that previously engaged learners learn to check out of school.

A Missed Opportunity

There are serious pedagogical issues with what happened here. For formative assessment purposes, how does this teacher’s answer help her understand, diagnose, and correct what Oliver’s potential misunderstanding is? For the purposes of developing student agency, how does her decision to not allow Oliver to explain his thinking limit his ability to sharpen his reasoning skills and disposition towards supporting his claims with evidence? It turns out that although his mistake could have been an association between lizards and iguanas or a mistake about what constitutes an “i” word (look at the second letter in lizard), it really came down to what happens when you start school in Zoom using the Arial font where a lowercase L and uppercase i are the same character: “l.” But because the teacher moved on without stopping to investigate Oliver’s response, that reason was not uncovered in class.

Mistakes are a natural part of learning, but students cannot develop into critical thinkers if they regularly freeze out of the fear of making a mistake. As educators, we can shift the culture of our classrooms to embrace mistakes, and one way to do this is through mistake analysis, one of several powerful but practical strategies I share in my book, Thinking Like a Lawyer: A Practical Framework to Teach Critical Thinking to All Students. (Bookshop.org | Amazon). As a math-teacher-turned-attorney, I wrote this book and started my organization, thinkLaw, to help educators seamlessly incorporate critical thinking into their curriculum.

Critical Thinking as a Pathway to Equity

I have a confession: I’m in this for the rule-breakers. Our profession attracts many people who became educators because the compliance-based, rule-following system worked well for them. But I was not one of those people. As a young student, I had a lot of behavior challenges, but it turned out these were the result of not being challenged. It was only later in life, when I attended law school, that I was taught the kind of critical thinking I needed when I was younger, the kind of thinking that would have kept me challenged.

Critical thinking should not be luxury good. But our current system often treats it that way, setting aside this kind of challenging work for only the most advanced students. In conversations about equity in education, one question I always ask is How do we make equity real at the classroom level? We can talk about implicit bias all day, but what about the explicit bias of saying “These kids can’t”? What “These kids can’t” often means is “As an educator, I have no idea how to create learning conditions such that all kids can.”

So I decided to create spaces that rewarded disruption and divergent thinking—spaces I longed for when I was going through the K-12 system. I view access to critical thinking as THE pathway for making equity real at the classroom level by giving students the opportunity to lead, innovate, and break the things that must be broken as a core part of their educational experience. This is not possible in a world where students are afraid of getting the wrong answer.

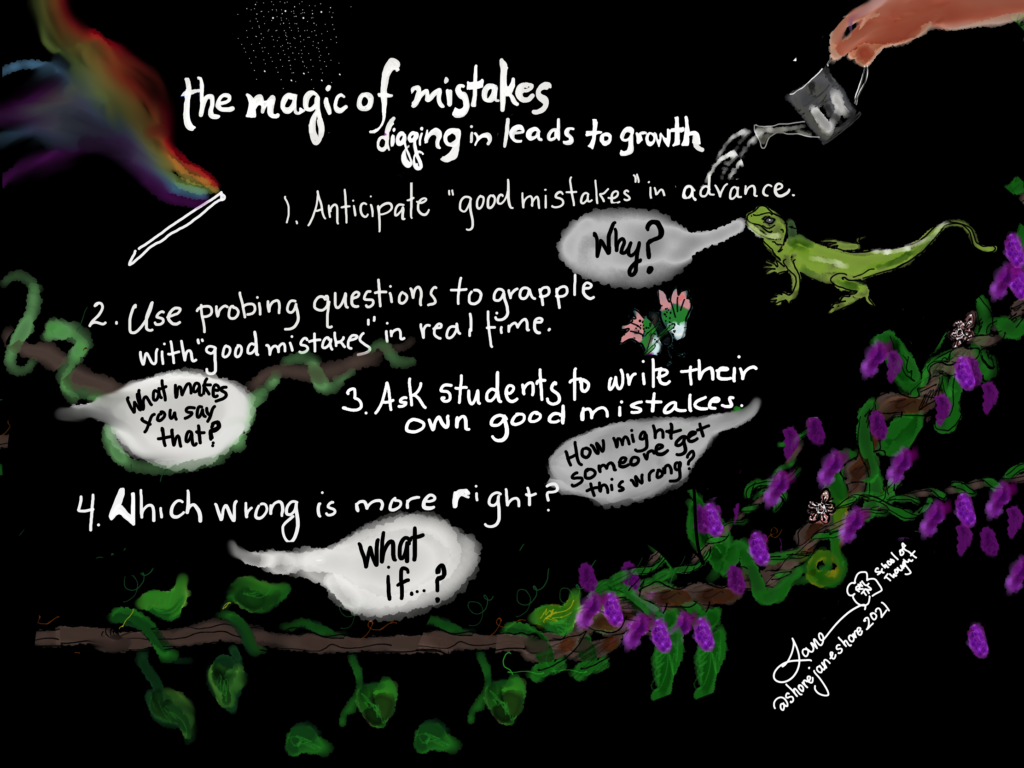

Four Ways to Implement Mistake Analysis in Your Classroom

The magic of mistakes is not a belief system. It is a practical set of tools you can apply in almost any classroom context, regardless of grade level or subject area. Here are four strategies you can use to leverage mistake analysis as a seamless way to incorporate critical thinking into your instruction:

1. Anticipate “good” mistakes in advance.

When planning for instruction, think ahead about the kinds of mistakes students are most likely to make. You already know how students will get confused when adding fractions with unlike denominators. You can predict that some students might confuse fact with opinion when the statement is “pizza is the best food ever” (because it is).

But don’t stop at identifying WHAT students may do incorrectly. Make sure you think about WHY the mistake may happen so you can do a better job in your instruction to show them HOW to prevent that mistake. For instance, if a student tells you that 5 + 2 = 6, you should anticipate this to be a common mistake that occurs when students start their counting with an addend, which sounds like, “Okay, starting with 5, I’m adding 2, so 5, 6. The answer is 6.”

2. Use probing questions to grapple with “good” mistakes in real time.

Teacher: Who would you argue is most responsible for the assassination of Malcolm X?

Student: John F. Kennedy.

This real-life classroom exchange shows why it is hard to prepare for the infinite universe of potential mistakes. But do not be so quick to dismiss a student’s answer as totally off-base. They offer a lot of opportunities for learning and some of them have the potential to be “magic.” Instead of moving on so quickly, try some of the following probing questions:

- JFK? Interesting. What makes you say that?

- Why might some of your classmates disagree with you?

- JFK was assassinated before Malcolm X was. Help me understand why you believe he is responsible for the assassination of Malcolm X. (Ask clarifying questions if the student’s timeline, scientific theory, mathematical concept, grammatical rule, etc., does not appear to be accurate, even after probing.)

If you simply dismissed this student’s answer as nonsense, you would have missed out on the clever connection this student made between JFK’s assassination, Malcolm X’s controversial quote stating that this tragedy was an example of “chickens coming home to roost,” and inevitably, a turning point in the growing tension between Malcolm X and the leadership of the Nation of Islam.

3. Ask students to create their own “good” mistakes.

“How might someone get this question wrong?” When we have students anticipate the most predictable mistakes that might be made on a task, we’re moving well beyond that lower level of test-taking skills and instead, getting students to think like test-makers, coming up with viable (but incorrect) options on a multiple-choice test.

Suppose your students struggle to identify the main idea of a passage. Instead of asking students to define the main idea of this post, for example, what if we asked them to create three wrong but “good” incorrect responses to what the main idea is?

- “Students get upset when they get an answer wrong” works well because we know how tempting it is to just read the opening of a piece and guess a main idea from that.

- “Mistakes can be magical” would be an answer a student might pick who only read the title.

- “Educators should anticipate likely mistakes in advance” is the first practical recommendation, so a student might mistakenly choose this response as the main idea.

It’s important that when students do this, they come up with logical possibilities. I have my students follow what I call the “Joe Schmo” rule: What kind of answer would trip up Joe Schmo, the average person who always falls for the trick answer? Instead of letting students come up with crazy, nonsensical options, this rule keeps the exercise at a challenging metacognitive level.

4. Which wrong is more “right”?

Mistake analysis can also be an opportunity to introduce conflict, drama, and meaningful opportunities to write and debate across content areas. As an attorney representing clients in business disputes, I rarely had a case where one side was pristine and the other was pure evil. They were usually both wrong, to some extent. But the core question was, which one is more “right”?

Bring this framework into your classroom by analyzing two equations that are both done incorrectly, but one has a computational error and the other has a conceptual answer. Two paragraphs or essays where one has structural errors and the other is riddled with spelling and grammatical mistakes. Two science experiments with flawed procedures because one has problems with omitted variable bias and the other struggles with selection bias. Asking which wrong is more “right” helps learners shift from asking “what” and “how to” to asking “why” and “what if” – a necessary shift for giving students the tools to not just analyze the world as it is, but imagine it as it ought to be.

I am a true believer in the magic of mistakes. To be clear, I am not advocating for a world with no wrong answers. I am advocating for a world where children (and adults) are less obsessed with being right and much more focused on the process of understanding what it means to do right. Care about social-emotional learning? There is tremendous empathy to be gained from learning why someone sees something differently than you do. Worried about how you can motivate students to engage in critical thinking? There are amazing instructional implications for planning for mistakes in a way that sets up a classroom culture where traits like compliance and risk-taking outweigh the default culture of compliance and rule-following.

When we don’t give our students opportunities to engage in critical thinking at all levels, we are systemically leaving brilliance on the table. By adding strategies like mistake analysis to our regular classroom practice, we’re tapping into that brilliance and making it more likely that all of our students will thrive.

Mistake analysis is just one of the many powerful but practical strategies I break down in more detail in Thinking Like a Lawyer and in the work we lead with school systems across the country to ensure critical thinking is no longer a luxury good. Learn more about what we do at ThinkLaw.us.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

This provided such a great perspective on how to respond to mistakes. As a relatively new teacher, this is something I’ve often struggled with. I’m definitely going to put these ideas into practice and check out your book!

Glad you found this helpful, Jenny! Thanks for letting us know.

Wonderful insight into critical thinking and mistake analysis. Thank you!

Consultants are the bane of the professional educator. This site needs more input from teachers who are grinding it out every day of the school year. Having to hear how everything you are doing is wrong by someone who might have spent a few years in the classroom is demoralizing.

WOW! I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed hearing Mr. Seale’s passion about teaching critical thinking. While transitioning from a career in the “real world” where I was REQUIRED to use critical thinking and understand the process so that curve balls didn’t derail me, I am struggling to even come up with words that adequately describe the level of SHOCK I have had to find out that we have traded teaching critical thinking for rote learning to appease the masses. I am sure I’m doing “something” wrong in between my noble efforts, but I can empathize w/APA by reading between the lines…. today’s academic environment (students and well-intention-ed teachers and administration) is less than helpful while trying to “grind it out” as APA refers. Although, I am not willing to disparage consultants who mean well and… maybe… “we all” NEED to take a listen and make some changes instead of following the “appeasement model” to save our jobs. I’m progressing towards extinction (potentially losing my job) over this very subject. Posting about this unspoken reality; although teaching critical thinking is at the TOP of the list of what we are told to teach, will probably speed up my next career move. Oh well, maybe I am a dinosaur and forgot that I am ALREADY extinct. Ha! So I guess this is my cry for help from Mr. Seale. COME HELP… but it will probably have to be pro-bono. lol. Come visit! I help my colleague who is working on a sense of community and inclusion in our not so diverse major/program/career. I would welcome you. Be prepared, you may find as I have that “your passion is annoying” in this environment. I ENJOY IT, KEEP IT UP! You got me excited today!

(Readers, please do not interpret this as bitterness, I am VERY passionate about teaching while knowing that I am probably not implementing critical thinking properly. I still believe we can make a difference, but it takes COURAGE to FAIL along the way)

My favorite response to all answers is “What makes you say that?” It allows for justification of reasoning and opens me up to hearing the thinking behind a mistake if there is one. The key I’ve found is to say it both when the answer is correct and incorrect because it fosters discussion and analysis and promotes dialogue in the classroom. I learned this particular phrase from PD I attended from Project Zero on thinking routines. I highly recommend diving into them: http://www.pz.harvard.edu/thinking-routines

As a teacher who loves this podcast and is coming toward the end of one of the worst years, personally and professionally, of her life, I have to say I was immediately turned off from anything helpful to be gleaned from this episode by the beginning anecdote. Yes I understand the purpose of the article and yes I agree that the teacher didn’t respond correctly, but I can’t get past someone taking a small mistake on the teacher’s part in an impossibly difficult teaching environment in an unbelievably stressful teaching climate and splashing it across a widely popular podcast FOR teachers, basically interviewing a parent who listened to a small snippet of an awful, unprecedented instructional section, judged it, and sells their own, private, left teaching to be a consultant version. I believe there is power in harnessing and appreciating the creativity and uninhibited freedom of consultants, but I also think it’s very harmful to the continuing societal narrative that teachers are inept, useless, lazy, uncaring, and that we can’t do anything on our own without outside, privatized instruction and imposition of curricula/frameworks/etc. Sorry to share such a negative view because I did listen to the whole episode and I appreciate some of the insights, but coming in the end of such an outrageous year of fear, insults, shame, guilt, and actual physically dangerous working conditions, I can’t listen to one more person tell us how badly we’re doing our jobs.

Hi Deidre,

I’m so sorry this hit you the way it did; that certainly wasn’t Colin’s intent or mine, and I can see in your writing just how exhausted and unappreciated you’re feeling.

For the last eight years, most of my blog posts and podcast articles have this kind of formula: I zoom in on some small detail in a teacher’s craft, then talk about how tweaking that detail can make a world of difference in terms of effectiveness. I can’t help but think of weightlifting as an analogy: When I’m doing a particular lift, one of my coaches might come along and say, “Hey, your knees are too far forward. If you move them back it’s going to be easier.” That’s pretty much all we’re trying to do here: turn a really common teacher move into a better learning opportunity. Responding to a wrong answer the way this teacher did is so common!! The anecdote wasn’t meant to highlight an example of unusually bad teaching; it was an example of something that probably every teacher has done hundreds of times.

As for whether someone who isn’t an active, practicing teacher has anything valid to contribute to teaching…? Well, that’s a criticism that has been lobbed at me from the very beginning, and in order to keep doing the work I do, I’ve had to not take that personally. I really hope that you’re open to ideas from people outside of the classroom, because we do have a lot of good stuff to share. If I went back to full-time teaching, I would have to stop doing this, and I think I’ve had some positive influence on education from this role I’ve created for myself. I hope that if you ever find yourself ready to leave the classroom, but you still want to use your training to help other teachers, you won’t let this resistance stop you. Teaching may very well be the most complex and difficult job in the world, and it takes a lot of heads to figure out how to do it well.

I believe you are anything but inept, useless, lazy, or uncaring. My guess is that you care deeply about your students, you strive to do high-quality work, and you do whatever you can to keep improving every year. I also know that this year has been unlike any other, and it has pushed every teacher to their breaking point. I sincerely hope next school year is better and brighter for you. Thank you so much for sticking with it.

As an educator who has struggled to address incorrect answers provided by my students appropriately without making my students feel discouraged to participate again, I found this blog post to be very insightful. As we move away from the academic curriculum where the sole purpose of education is to provide students with information, towards the humanistic curriculum where education is focused around the learner and their needs, it is important to adapt schooling to include the teaching of critical thinking skills and normalize making mistakes. In my personal teaching practice, I try to plan my instruction so that my students are developing self-regulated learning skills through inquiry-based learning. The blog post mentions creating a “world where children and adults are less obsessed with being right and more focused on the process of understanding what it means to do right”. This statement really stood out to me, and I think that the first step in creating this world is by normalizing making mistakes. When I was growing up, mistakes meant not doing well academically and getting a bad grade on report cards, which in-turn caused anxiety associated with making mistakes. As an educator, I ensure that mistakes are welcome in my classroom. One of the strategies I use to help my students be okay with making mistakes, is to point out my own mistakes when I make them. This not only eliminates the perception that the teacher is at the “top” of the classroom hierarchy creating a sense of equality, but also allows my students to feel that they aren’t the only ones who make mistakes. This also gives them an example of how to overcome their mistake instead of being discouraged from learning and participating. Out of the 4 strategies, the one that stood out to me was the use of probing questions. I have done this in the past; however, I’ve noticed that sometimes the students who I have asked the probing question to, feel uncomfortable and shutdown as they feel like they have been put on the spot. Overall, I really enjoyed reading this post as I feel that it was insightful towards my personal teaching practice.