Listen to my interview with Dan Ryder (transcript):

Sponsored by Public Consulting Group and ViewSonic

This page contains Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

Most teachers instinctively know that if students’ emotions are off-kilter in any way, if their stress levels are high or their social lives are a mess, they won’t be able to concentrate on academics. And yes, schools usually hire guidance counselors to support students with these issues, but most of the time they can barely squeeze this work in between all the other things they’re responsible for. Research is telling us that children and teens are experiencing more anxiety and depression than ever before, and those numbers keep going up, so clearly the need for social-emotional support in schools is growing.

Many of us do what we can to pay attention, to tune into our students’ emotional needs, build relationships with them, create safe spaces in our classrooms, and weave lessons about communication, anger management, self-advocacy, and mindfulness into our academic content.

Still, we’re pretty sure this isn’t enough.

Some schools are tackling this issue by providing mental health services as part of larger wraparound programs. Other schools are adding on separate SEL curricula, doing book studies, and giving extra SEL training to their teachers.

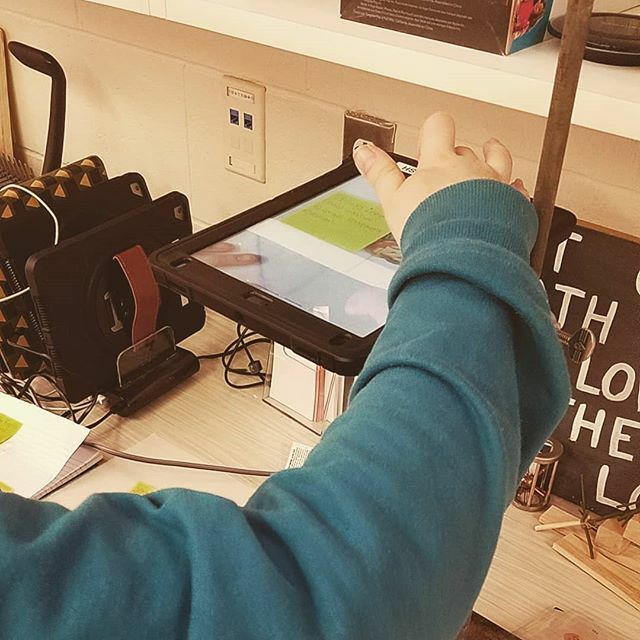

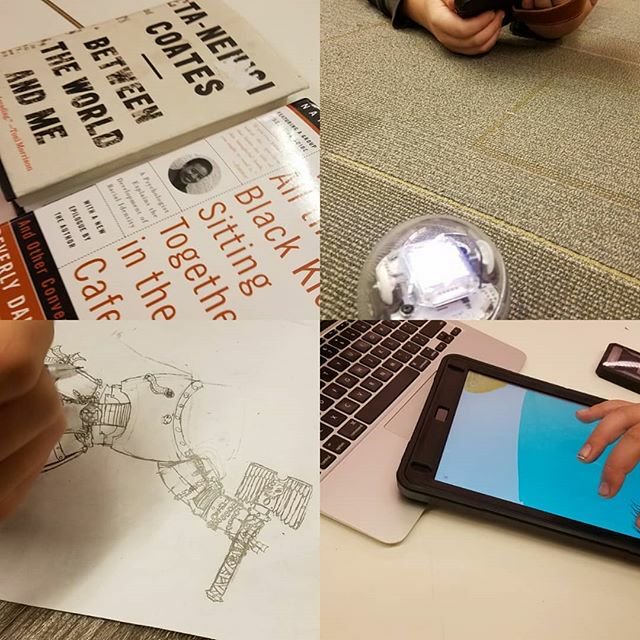

Another creative approach is to designate a space in school that can meet some of these needs. But in this case, we’re not talking about a counseling center or meditation room—although these would be welcome additions to any school. This space does not appear to have anything to do with social-emotional needs at first glance: You’d see a 3-D printer, piles of Legos, books, index cards, art supplies, laptops. You’d see students cutting paper, taping pieces of cardboard together, editing videos. It looks like a makerspace, because that’s what it is. But it’s more than that.

What is the Success and Innovation Center?

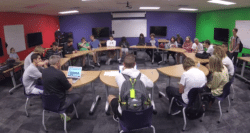

The Success and Innovation Center (SIC) is a unique space at Mt. Blue High School in Farmington, Maine. Director Dan Ryder describes it as a problem-solving studio, a stigma-free space where students can go at any time during the school day to work on problems they’re having inside or outside the classroom.

“It takes the best principles of human-centered design and the best principles of social-emotional learning and fuses them together so that through our space, the act of making and creating can also help with the other parts of ourselves besides just academic learning.”

Here’s how the center came into being: Several years ago, Ryder had already established a small makerspace in his own English classroom. “I started the makerspace in my room not because I wanted kids making things, but because I had adopted design thinking as my lens through which I was doing everything, and we needed to prototype solutions to stuff. So I kind of went into making in my classes from that place of doing need-finding, empathy work, really understanding what someone is like, looking at body language, listening to someone’s words and how does their diction relate to what they’re feeling, how do our feelings actually align to our actions, and what happens when they’re out of alignment?”

One early project in Ryder’s English classroom was to have students design sanctuary spaces for their classmates as a way of developing the idea of safe spaces, inspired by Laurie Halse Anderson’s book, Speak.

Over time, Ryder noticed that students who weren’t typically interested in or successful at school started to become much more engaged in these design-thinking projects. Soon more and more students were coming by his classroom makerspace to use it, and he dreamed of expanding into a larger space that all Mt. Blue students could access at any time.

Meanwhile, his colleague Becky Dennison had been working to help high school students transition into college. She was imagining a dedicated space for facilitating these transitions at Mt. Blue.

Eventually, Ryder and Dennison realized that their two separate visions for a student-centered space could actually work together. “I’m like, wait, this place could be a problem-solving studio,” Ryder says. “We were using all sorts of techniques in talking about this Success Center, we were using all sorts of methods that I was using with the design thinking kids. So I just brought it up while we were sitting around the table, I’m like, couldn’t we do both? You know, couldn’t it serve both purposes?”

Ryder and Dennison decided to join forces, they applied for and won a federal GEAR UP grant to fund the idea, and the Success and Innovation Center was born.

How the Center Works

As a general rule, the SIC is open to students on a flexible, as-needed basis, without a lot of restrictions. “(Students) can get a pass, I’ll write you a pass, you can come in from your study hall,” Ryder explains. “Your teacher can call down or send me an email and say, hey, can so and so come and work down in the SIC? They could use some help on something or they just need a space that’s not this classroom right now to work.”

He describes his role—and the way access to the SIC works in general—as similar to that of a library and librarian. “(A librarian) can push out, do work with classes, classes come down and work there in the library, sometimes it’s a one-on-one, sometimes it’s a small group, sometimes it’s split. I based my work and my role on that type of a model.”

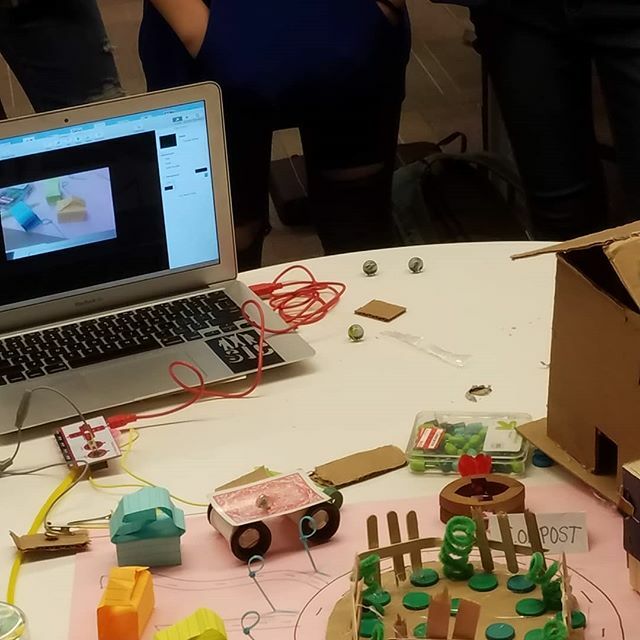

On a typical day, there might be one group of students studying for a test, while another student edits a video for a project, another writes code to program a robot, two more work on essays, and another drafts and practices an entrepreneurial pitch.

So how do social-emotional needs get met? So far it just sounds like a regular makerspace, right?

The way Ryder explains it, the social-emotional stuff often happens as a byproduct of the other work students are doing. Although some students do come in specifically to talk about personal problems, many more show up to work on something academic; the personal benefits just happen to trickle in while that work is happening.

“We really try to brand ourselves and market ourselves to the student body as ‘Here’s where you go when you’re having any sort of problem, academic, emotional, vocational, personal, whatever it is,'” he says. “A problem doesn’t have to be a bad thing. A problem can just be a question you have or something you’re working on.”

“Whatever is going on with them,” he continues, “it’s not working. So we try to find solutions that meet the kids’ needs and hold them accountable. We get the academic rigor in there and make sure that that’s not falling to the wayside. And in that process—by just being a kind of third party that is invested in only the student but not in anything else—we get to have some conversations and meetings and planning around these kids where I get to ask the kind of design questions around well, what is it that we’re really trying to achieve here, and what does so and so really need?”

Ryder says the SIC works best when run by two full-time adults: One who can “do a deep dive” with students on whatever problem they happen to be wrestling with, and the other to serve as a sort of facilitator, to coordinate student activity and document their comings and goings. The two can also balance out the work based on their individual strengths: One might be stronger on academic work, while the other might do best when handling the social-emotional needs.

exhibits of ideal neighborhoods, created for a project in one of their classes.

Creating a Similar Space in Your School

Ryder’s advice for teachers who want to establish something like the SIC in their own schools is to start by thinking of it like a library, where “students are encouraged to come in and access resources, and your librarian interacts with them and it’s very much about, hey, what can I do to be helpful to you today? How can I help you find the thing that you need? Because that’s what most librarians do; they’re really there to help navigate a need.”

With that mindset, he warns teachers not to get too consumed with filling the space with lots of expensive equipment. What’s more important is staffing the room adequately. “There’s a lot of things you don’t have to have, like 3D printers. Okay, don’t have a 3D printer. Who cares? What you need, I feel really strongly that one person isn’t enough. You really need two people.”

And not just any people, he says. “Two individuals who lead with empathy. When they’re coming through the door, the goal is not to get them to think the way you think or to do the thing you want them to do, the goal is to understand where they’re coming from. So if you lead with empathy and you approach a space like this from a lens of possibility, then like you don’t need piles and piles and piles of things.”

“It’s not all perfect,” Ryder concludes. “We just feel really strongly that what we’re doing is filling a space that we otherwise don’t think is getting filled on campus.”

For more from Dan Ryder, follow him on Twitter at @WickedDecent or read his book, Intention: Critical Creativity in the Classroom.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

I never thought the arts would go away, but they did. And with that, my job dissolved as well. For me, critical thinking and solving problems was part of my nature — always using Socratic questioning to help students navigate through life’s woes. After close to thirty years working with all grade levels (primarily at-risk youth), I was transferred back to the middle school I helped open in the 1990s. Here, I would teach eighth-grade English. In fact, all my paintings still adorn the office walls and teacher work areas. What stood out was the absence of the kinesthetic learning, i.e., drama, dance, visual arts, and any other modality a student could use to comprehend information in an active way rather than passive. Immediately, I formed a club for the “misfits.” We are the “Renaissance People” who help others see the world in a different way. My group of “kids” meets with me every day at lunch to play games, read plays, and dream the dream via “backwards design.” Years ago, I created a refuge for the artists, the philosophers, the poets, and the music makers where we could make connections out of what we all were learning (yes, I include myself) to real-world applications. Currently, our group is creating a talent show, art/lit magazine, getting a petition to put in stop signs/crosswalks at a “deadly” intersection and so much more. I could not agree more with the concept of a “maker space” because our students need it more than ever in this generation.

Rick, thanks so much for sharing your experience. It sounds like you have an authentic dedication to help kids succeed. It’s refreshing to hear accounts of teachers advocating for students and the practices that serve them best.

Very explanatory, comprehensive and knowledgeable note.

We’re glad you found it helpful!

The resources are very useful

Are there any grants available for creating these spaces?

Kathleen, there’s a section towards the end of the post called “Creating a Similar Space in Your School” that you might find useful. The podcast episode goes into a bit more detail about Dan’s grant and how to get started.

You’ll find that there are state, local, and private grants for education available if you have a strong idea for a project. There are also crowdfunding opportunities like GoFundMe and IndieGogo. you might want to explore options along those lines. Hope this helps!

Resource is very helpful