Listen to my interview with the Apollo School founders (transcript):

We’ve reached a point where most teachers embrace the idea of student-directed learning, the philosophy of being the guide on the side rather than the sage on the stage. We can also appreciate the value of cross-curricular studies, blending math and science, for example, or integrating arts and music into history class. So why are so many teachers still using the same old model, where we plan and deliver lessons in separate subjects, in lock step, using the same traditional schedule as we always have?

Two reasons, I think.

One, because it works, more or less. We move students through the system, they learn some stuff, pass tests, and graduate with an acceptable repertoire of knowledge and skills. Acceptable. Enough to function, to continue on to college and survive, more or less.

Except that lately, more and more voices are telling us that this repertoire of knowledge and skills isn’t quite cutting it. Students aren’t quite as adept at problem-solving and collaboration and inquiry as they need to be for the 21st century.

The other reason we stick to the traditional framework is the one I believe is more powerful: It’s because we don’t know how to change. We have no template for what school could look like if we restructured it to reflect priorities like cross-curricular connections, student self-efficacy, and inquiry-based learning.

Well, I have a template for you today, and I can’t wait to show it to you.

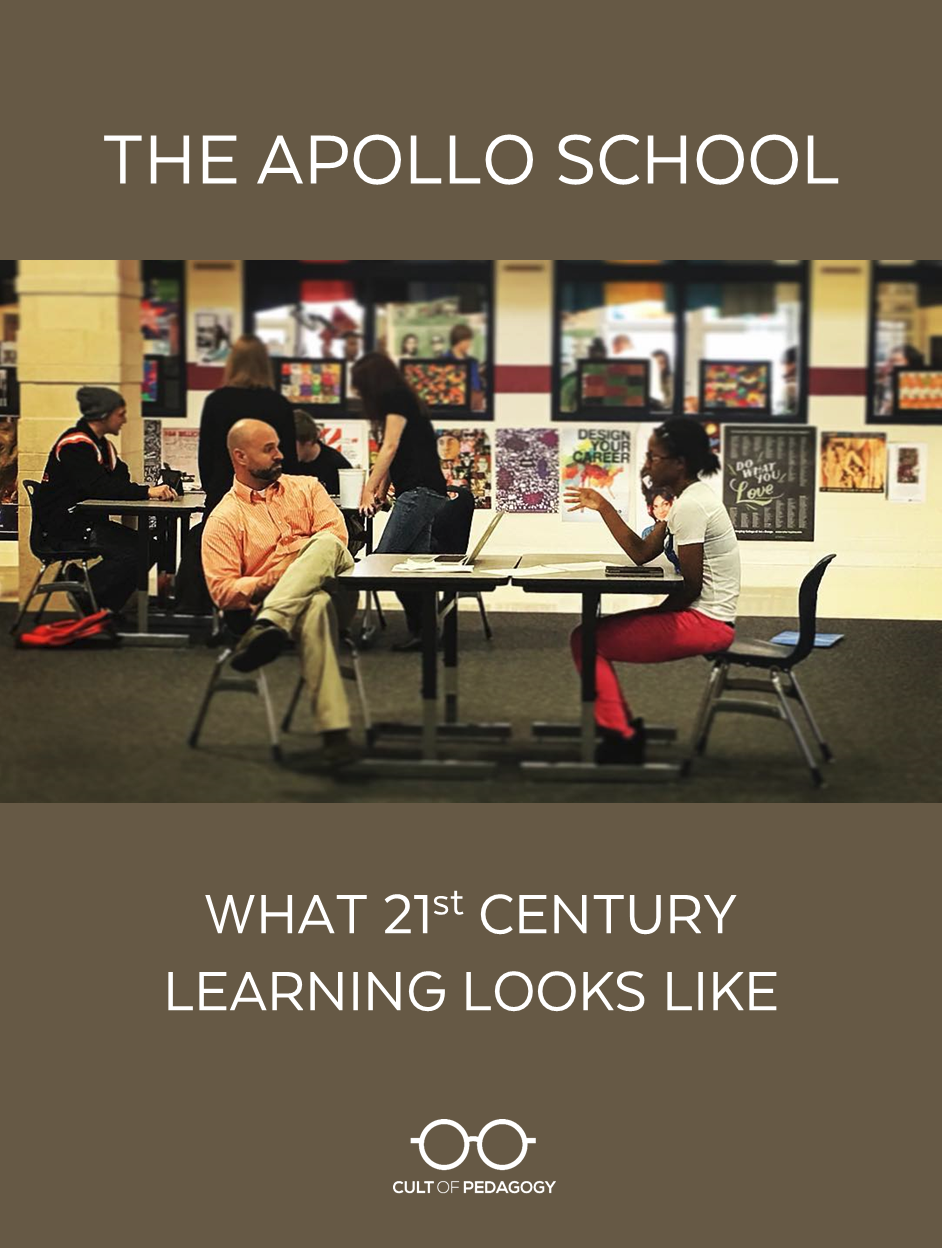

Welcome to the Apollo School

The Apollo School is a program that operates inside a regular public school, Central York High School in York, Pennsylvania. Apollo is a semester-long, four-hour block of classes—English, social studies, and art—all blended together and co-taught by three teachers, one from each subject area. Throughout the semester, students are responsible for designing and completing four major projects, each of which is aligned with standards in all three subject areas.

Students set their own goals for each day based on whatever project they happen to be working on at the time: This includes independent and group work, one-on-one appointments with teachers, and attending optional, self-selected mini lessons taught by the teachers. By lunch time, when the Apollo block is over, students resume a regular schedule for the rest of the day.

How the Program Started

Apollo began when Greg Wimmer, a social studies teacher, and English teacher Wes Ward (pictured above), started playing around with the idea of combining their two classes. “Every time I would teach a piece of literature,” said Ward, “I’d find myself talking about history. And I thought how convenient it would be—and really beneficial to the students—if they could have a history buff here to really challenge and push the kids to dig up more context of the poetry or stories we were reading.”

Meanwhile, their school district was already shifting its whole instructional paradigm. Embracing an approach called mass customized learning, Central York School District was looking for ways to personalize the learning experience for every student. This approach was influenced by the work of Bea McGarvey and Charles Schwahn in their visionary book Inevitable: Mass Customized Learning: Learning in the Age of Empowerment.

This video explores that district-wide shift:

With encouragement from their principal, Wimmer and Ward joined forces with Jim Grandi, Central York’s art teacher, and the Apollo School was born. They gave a presentation to prospective students the semester before the course started, and interested students in grades 11 and 12 enrolled voluntarily.

Central York still offers traditionally taught English, social studies, and art classes. This choice is all part of the variety offered by mass customized learning. “We have some courses that run in a hybrid format where they may meet with a teacher for a little bit but then be working independently or in groups, and then they’re meeting back with the teacher again,” explains Ward. “We have online courses where students check in once a week with a teacher, but the rest of the work is done online. So mass customized learning isn’t necessarily Apollo. Apollo is one spoke of that wheel.”

Course Requirements: Curriculum and Assessment

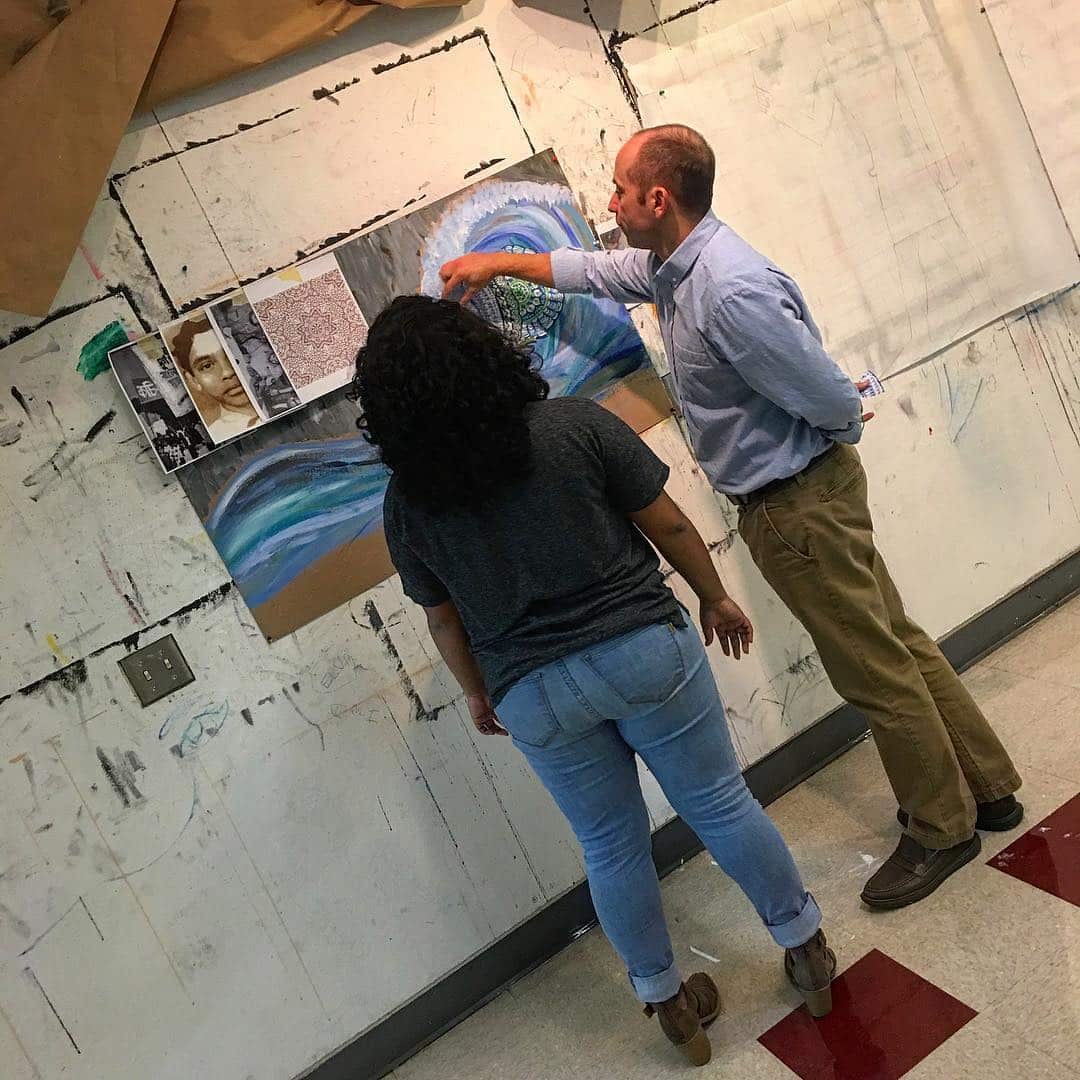

Over the course of a semester, Apollo students are required to complete four independent projects within a given theme, each of which must include some element of English, social studies, and art. Students are given a list of the required standards in every subject, and they are expected to meet each of these by the end of the semester.

“Since you have 40 students running in 40 different directions,” Wimmer explains, “we decided they were the ones that needed to self-select the standards.”

Ward describes how the process works. “At the start of every project, we have the students kind of designate which standards they’re going to work towards, either showing mastery of or just practicing to get better at. Unlike most classrooms where the teacher is drawing up the lesson plans based on standards that are some invisible thing under lock and key, we actually share PDF files of all three of our subject area standards with students. They have them all semester long, so they’re constantly aware of the expectations from each of us and what they’re supposed to be mastering.”

How students meet these standards is entirely their decision, and the road is not always smooth. “It’s really genius to see them a week into their project realize that they’re hitting the wrong standards,” Wimmer says, “and then they go back and are able to change them and make the standards work for them.”

When a project is completed, students meet with all three teachers in a setting not unlike the defense of a doctoral dissertation: They discuss goals, process, and outcomes, and explain exactly how they met each learning target. Students are also assessed on how well they met four thinking skills—reasoning, perspective, contextualization and synthesis—and two “soft skills”—communication and time management.

The whole group meets at the beginning of each day in Family Time.

A Typical Day

Each day starts with Family Time. “Around 7:45 we kind of corral them together into Greg’s room and we call that Family Time,” says Grandi. The length of that meeting can vary dramatically, from five-minute housekeeping sessions to hours-long conversations. “We’ve had full-on one hour to two-hour discussions where they’re really generating the conversation and driving the topic about their own education. Those can be completely organic in that sense, and really rewarding.”

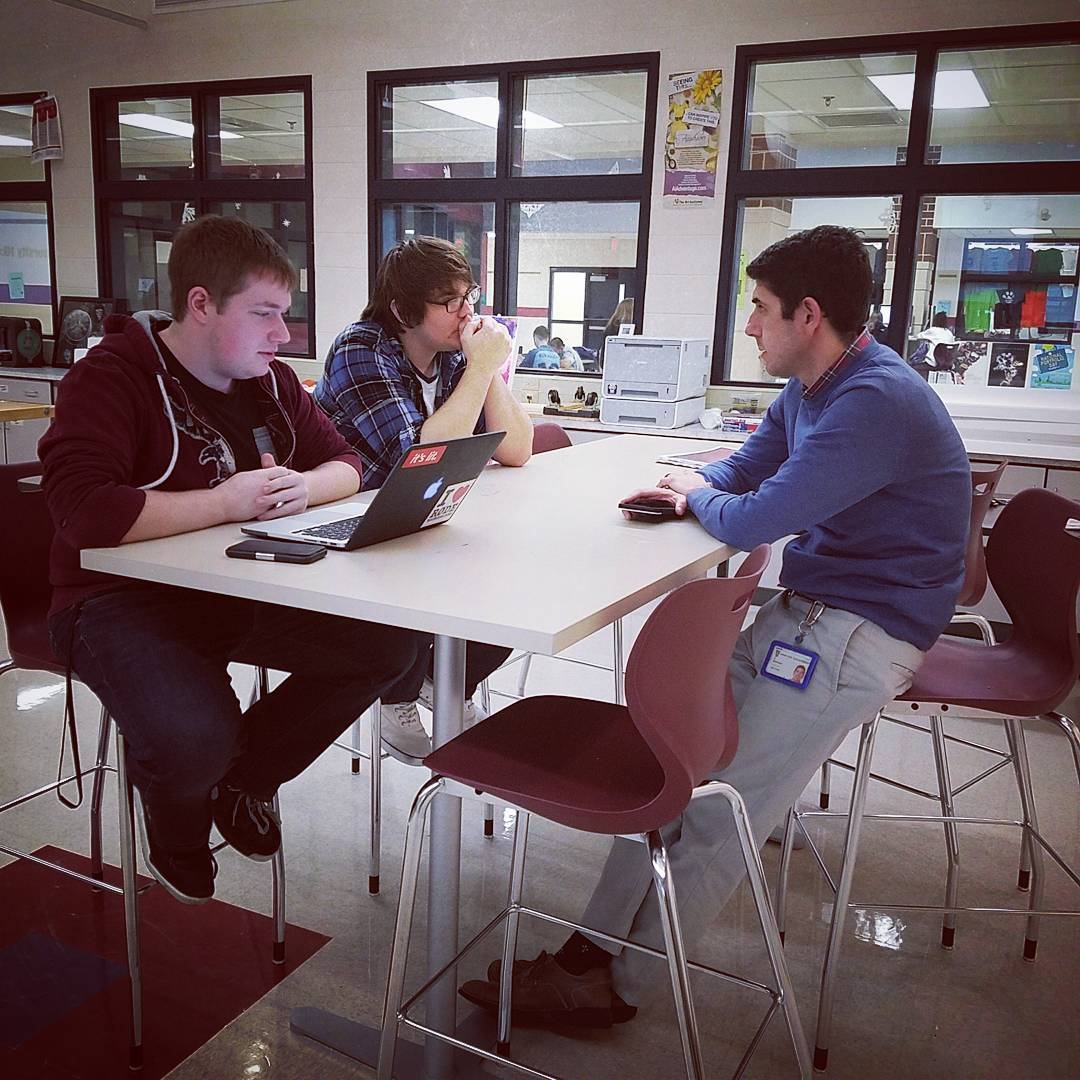

Students use online software to plan out how they will use the four hours, in 30-minute blocks of time. This time might include independent research, creative work, group work, or one-on-one conferences students schedule with the teachers as needed.

Students meet with social studies teacher Greg Wimmer. Using an online form, students schedule one-on-one conferences with teachers as needed.

They are free to travel between the art room, which functions as a kind of makerspace, Wimmer’s classroom, which students typically use for small group meetings, and Ward’s room, which is often used as a quiet space for students to work alone.

“They can also go to our library or sit at one of the tables that’s around our school and in extreme situations,” Ward says, “they might even leave the school to go interview somebody in the community or to go shadow somebody in a certain career. We really try to push them beyond that normal setting.”

Each student decides how to use Apollo’s four-hour block of time. At the end of each project, time management is part of their final assessment.

Mini-Lessons

Another option students have in that four hour block of time is attending mini-lessons. Rather than teaching whole classes the same lesson at the same time, the teachers plan and teach optional mini-lessons within their subject areas. Some lessons cover basic content areas that meet certain standards, but most are delivered only after teachers see a need within the scope of what students are working on.

Optional. Did you catch that? Students are not required to attend mini-lessons; they choose to go based on their current needs. During family time, the teachers will advertise the lessons they are teaching that day.

“It’s kind of like going to an education conference and having that smorgasbord of possibilities to choose from,” Ward explains. “So it’s entirely possible that Greg would be teaching a lesson about this particular conflict or this issue in current events. And Mr. Grandi might be offering an art lesson at the same time that I’m offering something in English, and the students get to pick and choose which one is more beneficial to them in their project at that point in time. We can turn around and offer the same lesson the next day, and they can switch and go to the other one, if need be.”

The customization doesn’t stop with the teachers: Students can also request mini-lessons on specific topics. Grandi recently had a student request a lesson on Frida Kahlo and other artists inspired by her. “So I said, ‘Yeah, just give me two or three days to put that together and then I’ll have that lesson for you.'”

Some mini-lessons are even taught by the students themselves. “Every student usually has something they can add to the group,” Wimmer says. We have some students that are extremely good at technology, some who are good at building an online presence, and so we thought, why not have those students share their abilities and talents with one another?”

Art teacher Jim Grandi conferences with a student. Each student project includes an element of English, social studies, and art.

Positive Outcomes

When asked whether the program has produced the results they’d hoped for, Grandi says students go far beyond what they’d be able to do in a more traditional program. “When I’m teaching traditional classes, I try my hardest to plan really interesting lessons and projects for the kids to do. But I can’t plan these projects. I could never plan a bioethics project for the whole class. I couldn’t even hit all of the standards that I wanted to it. This way, (students) hit more standards as a class than I would ever have them hit if I was directing every single lesson.”

Academics aside, the program has allowed teachers to develop the kind of relationships with students that just wouldn’t be possible in a regular setting. “We’ve had some of these young adults come up to us and just … things I’ve never even thought I would hear,” Grandi says, “about how they would be scared to death to come to school Sunday night from anxiety, and how they love coming to school now, and they never have had conversations with adults or their teachers before, more than just, ‘Here’s your homework, here’s your test.’ We have real conversations with these people, I mean, these are people. The relationships you build are amazing.” ♦

Learn More About the Apollo School

Website: theapolloschool.weebly.com

Instagram: @apollocyhs

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll also get access to my members-only library of free downloadable resources, including my e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading!

I teach middle school. In my mind some of my students (and different ones on different days) would not be able to handle the self motivation. They would be messing around. If this program has some of failures, I would believe the more wonderful part. I see that it is a student choice… is there a “this program does not work for this student?”

Hey Monica! I’m going to ask Wes, Greg, and Jim to come by and respond to this. I’m sure they have had some students for whom this wasn’t a good fit. I would also love to hear how they handled it.

Monica, thanks for the question! You are correct in your statement that “this program does not work for this student”. We (Apollo) stress to everyone, students, and staff, that the Apollo program is not for every student. Motivation is a key ingredient for student success in Apollo. While we have shared some of the success stories, like I mentioned in the podcast, we have had some learners who have not faired as well. This usually happens when the learner has either poor time-management, no passion or interests they want to pursue, or simply fail to communicate with us (facilitators) at all throughout the process. Essentially, disappearing for four (4) weeks. We are anticipating starting a 9th and 10th-grade cohort next year. Like you said, middle school students might not be able to handle the self-motivation. We are planning to guide them more in the beginning and let the leash out slowly. Basically, teaching the time-management and communication (soft-skills), while helping them cultivate their curiosities. It is a process. There are no guarantees. But we have had a lot of success.

What did the teachers do for learners who have not fared as well or have failed to communicate with you? Did you offer them different options? Why did you use negative comments for those who did not participate? Did you think if your program may not work with all students?

Time-management is a practical life skill that we should include in elementary, middle, and high school.

I have used this model of teaching in my multi-age elementary classrooms. Our day began with class meetings and large group lessons. Next, we would move into our 3 hour work cycle. During that time, my students recieved mini-lessons, worked independently and cooperatively. I was able to perform ongoing assessments and address my students needs immediately. I served as a guide to help my students during their journey of self-guided discovery throughout our cultural curriculum. At the end of each week, my students reviewed their workplans to check for accountability. Incomplete work was added to the workplan of the following week. Students were intrinsically motivated and proud of what they had accomplished. I enjoyed listening to the podcast. Thank you.

I found myself reacting strongly to the second reason: “It’s because we don’t know how to change.” I think this reason is more accurate: Many of us are not given the tools and resources to change instruction. We would like to–we see the possibilities, we have the ideas–but we’re hamstrung by shrinking budgets, no planning/prep time, and out-of-date or nonexistent technology (let me tell you about my 8-year-old classroom computers). In addition, I “should” be able to combine subjects easily to maximize instruction because I’m in elementary, and I try to whenever possible, but my specials schedule chops up the day so much that we barely start something before we have to pack it up and run to a special. And yes, as Monica mentioned, some students cannot handle this sort of freedom. More info on exactly how this program works. how it works at different grade levels and details on budget, technology and supplies would be extremely useful.

You make a good point, Barbara, about not being given the tools. My suspicion is that administrators are hesitant to approve changes like this because they don’t know if they are going to work. This is why I wanted to share this program here, so education leaders can see exactly how it could work. Feel free to ask more specific questions and I’ll have the Apollo teachers come by to answer!

Barbara, thanks for your questions. As a “special” and one-time elementary teacher, I understand exactly what you are saying. Elementary, like you stated, should be able to combine subjects. But far too often, specials are seen a prep period for the classroom teachers. We (Apollo) are fortunate. We have an administration, from the superintendent, down the building principals and a school board that recognizes there is a need for change in education. We are a 1:1 school, and are supported fiscally and philosophically. I wish I had an answer for you. It would be very difficult to do this program without administrative support. Like Jen said, we need administrators to begin to listen to these ideas, and others out there, that push to make student learning more meaningful and passionate. One of the skeptical questions we do get from visitors has to do with measuring traditional student growth, i.e. “How do well do your students test?”. We have given our students the S.R.I.(Scholastic Reading Inventory) test. The Apollo students had a 50% higher average increase than the entire school. Some administrators really like hearing that.I hope this helps a little. If not, let us know, and we will try to answer all your questions.

Can you tell us a bit about how math is taught? Is it the “old-fashioned way” and the kids just attend a regular class during their day? Thanks.

Hi Jennifer, this is less of a content question, but I was wondering what program you’ve been using to record your Skype interviews for the podcast? I’ve been looking around for a good way to record audio for a couple different projects I’m planning out, and as you mentioned the new software you were using for this episode, I realized that you might have some good suggestions! Any help would be greatly appreciated.

Hey Patrick! For a long time, I used Call Recorder, which is used to record Skype calls on a Mac. This was the first interview that I used a different app, called ZenCastr. So far, I really like it! You can find it here: https://zencastr.com/

I had only positive reactions to the Apollo School and what it is accomplishing. My mind instantly went forward to next year and how I could change students’ learning for the better. While choosing one’s own standards would need some fine-tuning at the lower grades, I bet the results could be amazing.

Thanks for providing such a wonderful article about a dynamic public school. My question is pretty similar to what has been posed in previous comments. How are students and staff supported in a transition to this model? It seems students can elect to be a part of this model of learning, I assume this choice leads to a higher buy-in and engagement from them. I ask because I was a middle school teacher and the high school my students eventually attended to had a vision very similar to Apollo School’s practice. As a co-teacher in history (special education and content co-teaching) I was thrilled when the new model of student centered and cross-curricular co-teaching was proposed in our district. Unfortunately, the feedback I received was often negative. Former students said they often felt confused and wanted more guidance. Teaching peers at this campus expressed frustration about not knowing how to shift instruction, student support and engagement, and their own expectations to this new model. Jennifer, if you know or if anyone from the Apollo School stops by to answer questions, I’d love to know how administrators, teachers, staff, and students who are used to traditional school structures are supported in the transition to the Apollo model. Additionally, how is student success within this model defined and measured? I know I sound SUPER traditional ed with that last statement 😉 but, I hope to gain an understanding of how Apollo works to assure this model is accessible to all students and how you support students towards their unique goals and future plans. Thanks!

Hi Erin,

Apollo is one of many learning options students have at Central York High School. So while it’s accessible to all students, it’s certainly not for all students. For example, a student might thrive in a lecture-based classroom and, therefore, he or she chooses that traditional style (we still have those classes).

As for teacher and student preparedness, we’re figuring it out as we go, knowing that communication and a lot of patience goes a long way. We certainly don’t expect students to arrive and thrive in Apollo without any previous experience in that kind of setting. For teachers, the district does provide in-service trainings but because many of these progressive styles of teacher/learning are new, we typically remind ourselves of best practices and how students learn best.

Hi – I’d love to know what program the “test-tube” student used for her digital mind-map. Thanks for a great episode… I’m inspired!!

Hello Bonnie- Apologies for the late response. She used an application called “MindMeister”. Like most applications, there is a free version, which is limited, or a payed version with extra features. Good luck!

This podcast has been truly insightful and motivating! As a 5th grade teacher I’m trying to figure out how this would look at the intermediate level of elementary. In the podcast, Jim, Wes, and Greg mentioned their district adopted this way of teaching. I’d love to know more of what this looks like at the elementary level.

Hi Nick,

Currently, Apollo is offered only at the high school. Our entire district, however, has adopted a mass-customized learning initiatve, which promotes student choice and varied instructional styles to optimize learning. The goal isn’t to “Apollo-ize” each grade level but, instead, to create learning environments for students who learn in different ways.

Hi Nick,

If you start brainstorming for the 5th grade level, I’d love to work with you.

Ana

I’d love that Ana. Perhaps we can talk about what this could look like.

I second that, Ana! I teach 5th grade and I am constantly trying to find ways to give my students more choice in how they show their learning, so I was fascinated listening to this podcast. I would love to hear what people have to say about how this could be used in elementary schools.

Hello,

Has there been any collaboration on what 5th grade would look like? Also, I didn’t see a response to the question about math- I teach fifth grade math and would really like to move in this direction.

I have a couple of logistics questions going through my mind that I hope someone at Apollo can address. First question is around teacher planning time and day. When you are not in the Apollo “block” of time, are you assigned more traditionally based classes? What kind of teacher prep time are you given within your day to plan the mini lessons, assess student work and give feedback, and collaborate with your colleagues? Is this prep time equal to the time given to the other teachers in your building? And lastly, I am curious about how scheduling worked for your program when you have three teachers assigned to a dedicated chunk of time with student load in the forties. Doesn’t this model load up the other teachers in your building with higher class sizes? When our middle school incorporated a project based team this year, it created some huge class size issues in other areas. This truthfully has led to some nightmares regarding student management in some cases and class sizes that are just not workable. Also, you mentioned that this program does not work for all and that students need to be motivated. Motivation or lack thereof is one of our greatest issues in our urban middle school. How do you prevent a program like this from becoming a more “elite” program for kids who “can handle it”, and thus creating a less than desirable environment for students who lack motivation to be in a program like this?

After rereading my questions, I feel like they have a negative tone, but truthfully, our District is seeking to incorporate just the same type of innovation that is mentioned in this podcast. Please read my questions from the basis of , “This is so cool! HOW MIGHT WE DO THIS?” I am eager to learn.?

Hi Tami,

Our high school runs on a 4-block schedule (80 minute classes). Apollo meets for the first 3 blocks, then all three teachers have a common planning period during the 4th block. The amount of planning time is equivalent to all other teachers in the building.

With a teacher-to-student ration of about 1:15, yes, other classes can grow in size, but it’s no different than other classes with small numbers that leave others with more students. Classes in our building range in size from 12 students to 30+. While it might be ideal to balance those classes, it’s just not the reality and might not ever be.

Apollo isn’t for everyone but everyone is capable, if that makes sense. We focus heavily on soft-skills, especially time management and communication. For students who struggle with those skills, Apollo can help improve them; however, it might not be the most ideal learning environment for them. We pride ourselves in that we have a range of student abilities in the course: IEP students, gifted, and several in between.

Thank you so much for this! I am a parent with a child in third grade and a two year old. I am not satisfied with the current state of education and am preparing a plan to move forward a similar concept in the education system. Is the Apollo school part of public schooling system? I would love to see student led learning happen rather than just teaching, which my son actually finds boring! I would love your help and support

The Apollo School is part of a traditional public school in York, Pennsylvania. The district promotes learning options, so when students sign up for a course, they choose between traditional, self-paced, hybrid, Apollo, etc.

I too am interested in the logistics. What is the planning schedule? How many students is each teacher “responsible” for? I work in a district charter school in Florida with seven periods of classes. I get one planning period to grade, plan, and do paperwork for my 110 sixth graders. I think this model looks great, but I don’t know if it’s feasible within the logistics of my district.

Hi James,

We’re blessed with teacher-to-student ratio in the Apollo program. The three teachers oversee 40-50 students, which makes the learning intimate and genuine for each student. We realize this isn’t everyone’s reality.

Wes

I identify with all the questions above. It’s not that I don’t want to implement this kind of program, I really do! I have a hard time determining how to integrate subjects and cover all the standards. I understand that Apollo school puts this on the students, but ultimately, I am responsible for students on state tests. I think the high stakes state testing is the ultimate reason teachers (at least me!) are afraid to try anything new. That and a lack of clear insight and student buy- in. I try to let my students design projects and they just look at me with blank stares and say they don’t know what to do. I really want to do this, I just don’t know how to make it work and still maintain a life outside of school. I appreciate the article and all comments here.

Bravo everyone at Apollo! We approach teaching and learning in a similar way at Mount Tom Academy located on the campus of Holyoke Community College in Massachusetts.

Hi,

I love the idea of this programme and see how it can work well with particular subject combinations. I’m a languages teacher, so I’d really appreciate any tips about how I could involve a languages department effectively in cross-curricular units- at present with five different languages and students of all levels within them, it is extremely difficult to plan anything where all students (including those with limited language) could be involved and actually still be learning new language, rather than just practising using their existing language. The latter is of course beneficial and necessary, but wouldn’t work for an extended period of time. Is there a way of involving language acquisition without there being too much of a burden on the language expert to translate and simplify other content knowledge?

I have always advocated self-directed learning using different scaffolding techniques to learning. It places the joy of learning on the child. They can learn at their on pace with the teacher acting more of a guide. Great post! Good to keep sharing until it is appreciated.

Do you think there would be a place to adapt this for middle school students with learning disabilities such as dyslexia, dysgraphia, and ADHD? They have great difficulties with time management and long range planning as well as processing. BUT all are intelligent. I’m thinking this could be a way to improve their time management skills, especially those going off to high school. Currently, they are very fearful of letting go of structure and guidance and hand holding. Even genius hour was a a bit of a flop, but it doesn’t mean it couldn’t work again with a different lens such as this. At my small school our job is to prepare them for reintegrating BACK into public school. I have a lot of freedom with our programming and would love to test run this in a small way ( 8 students ) in our last term of the year for 3 months to see how they do.

Sounds interesting and valuable, and perhaps a bit like a micro-IB program.

(chuckling) Off-topic: As a photographer, the faux-bokeh in the lead-in picture makes my skin crawl. Probably a manipulation of a stock photo, but… the source matters not. (shudder)

Hi Jennifer,

You asked “why aren’t more teachers using this model?” Your response was because it works and we don’t know how to do it any other way–paraphrasing here.

I have to disagree or at least add that do we get to choose? INME, not a chance. The district chooses, then makes sure ball-busting administrators in the building implement mindless test prep practices that serves no one. I just had to go there because there are creative and tech savvy teachers who are beaten down year after year by incompetent leaders. Not being combative, but many of us have the know how to usher our students into the 21st century, we are just made not to by threats of reprimands and non renewals.

Hey Keisha,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts here, and I apologize for not being clear. When I asked why so many teachers were still using older models, I guess I was really thinking on a larger scale. I do realize that school leadership makes the final call on the direction schools move. My hope is that by shining a light on programs like this one, I can help push things in that direction so teachers like you can ultimately create classroom environments where your students will really thrive.

Under the heading, “A Typical Day” you say, “Students use online software to plan out how they will use the four hours…” What is that software that they use?

Nate,

We use a software called “SCHedOOL” that was actually developed for Apollo by Eduspire Solutions.

I have to remark on this because in the 1980s my husband, the English teacher and his college, Greg, the science teacher joined forces to teach a 2-hour social studies/English block. They did all of the components mentioned here including the art projects. It was novel back then and the students were delighted to work with their teachers in this style of learning. This was all possible due to a school leader who had a vision beyond any leader I have seen since. True, the talents of these two remarkable teachers were unquestionable but I truly believe that this could have been replicated in schools across America. I hope your post gives this thing wings!

What do you think a program like this would look like in the sciences? I teach HS chemistry, and there is a great deal of direct instruction which would need to take place. Turning kids loose with a box of chemicals and equipment would be not only irresponsible but potentially dangerous. The kids in my urban district have been spoon-fed for so long that even the most basic inquiry lab requires a ridiculous amount of scaffolding, to the point where it doesn’t remotely resemble inquiry anymore. I think the whole premise sounds terrific, but I’m struggling to visualise implementation in these circumstances.

Hi Apollo teachers! This makes me think about what Penny Kittle and Kelly Gallagher write about multigenre projects in their 180 Days book. This worked SO well for my 10th and 11th grade ELA students.

Two questions:

I’d love to know more about the mini lessons students sign up for. How long? Are they designed based on skills they apply to projects, or are they meant to help with the production of the projects themselves?

Also, what does assessment look like? Any resources you can share?

Keep up the incredible work!

Hey Lindsay, for more information/resources on Apollo mini-lessons and assessment, you might consider following up with the Apollo team at their website. Thanks!