I used to plan my day-to-day lessons like this:

Jot notes on what I wanted to teach each day of the week.

Amend as needed.

That’s it.

Let’s be honest. Who’s got time to write full lesson plans? For every class? Five days a week? There’s no way to know what’ll happen Friday when so much changes on Monday. So I kept my plans flexible. As a veteran teacher, I know the topics to hit. And for the past several years, I’ve been doing the same at the college level.

The problem is that my notes were all over the place—replete with reminders, a question or two to ask, or a video link to show.

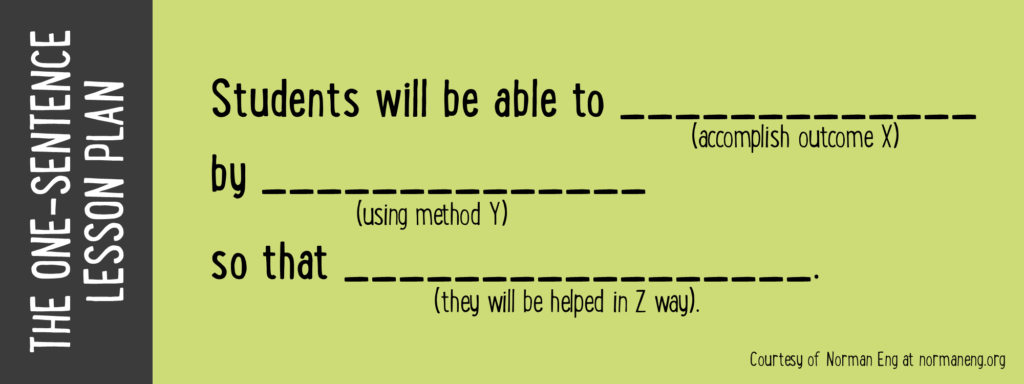

Enter the one-sentence lesson plan. With it, you only need to answer three things: The WHAT, the HOW, and the WHY.

The WHAT

First, WHAT do you want your students to know (or do) by the end of class? Here you identify the content or skill to be learned. For example, I want students to be able to evaluate the credibility of online sources. That’s a skill.

The HOW

Next, HOW will students reach this goal?

In other words, what method, strategy, tool, or activity will you employ to make sure they get it? Here’s where students wrestle with the content/skill. The HOW is typically hands-on.

Using the previous example, I might use one of the following:

Students will be able to evaluate the credibility of online sources by “triangulating” information.

Students will be able to evaluate the credibility of online sources by asking critical questions such as, “Does the author cite or provide links to research?”

Students will be able to evaluate the credibility of online sources by discussing in groups the pros and cons of each source.

The first two versions focus on a strategy, whereas the third uses an activity or method.

The WHY

Finally, WHY are students learning this content/skill?

This is the “so what?” part. Why do students need to know or do this? What’s in it for them? How do they benefit? Knowing your students is key to answering these questions.

The WHY may start with the prompt, “so that…” Continuing with the example of evaluating sources, I could state:

Students will be able to evaluate the credibility of online sources by “triangulating” information, so that they make better decisions.

The WHY is the most important part of the one-sentence lesson plan. It drives behavior, according to marketing and leadership consultant Simon Sinek. In his bestselling book, Start with Why (as well as in his immensely popular TedTalk), Sinek argues that top organizations understand that people won’t “buy into” whatever is being sold unless they understand why they’re doing it.

For instance, Apple clearly defines and communicates their purpose: to challenge the status quo in everything they do and to think differently. It explains why their products are simple, intuitive, and user friendly—and why they have wildly succeeded in a competitive industry. Other companies may push out bigger screens, longer battery life, or higher resolution, which, while nice to have, do not necessarily set them apart. The WHY is the emotional pull.

In teaching, we also need to define our WHY—for ourselves and for our students. Yet we forget the larger purpose in our dash to cover the curriculum. No wonder students keep asking, “Why do we need to know this?”

Another advantage of defining a WHY is that it can sometimes help you figure out your lesson opening. For my lesson on evaluating sources, I could start by activating students’ prior knowledge: “With so much out there, how do you decide what information to trust online?” Imagine the rich discussion that follows. And research is clear that students learn better when new content is “anchored” to existing knowledge and experiences. I start all my lessons with the WHY.

Putting the Plan into Action

Based on my one-sentence lesson plan, here’s a simple outline for a high school class period:

Opening: Ask students about their experiences searching for information online.

Mini-Lesson: Teach them how to triangulate information (or better yet, start by asking them better ways to find information).

Guided Practice: Model your “think-aloud” process for triangulating information by searching online for “Is climate change real?”

Activity: Students apply the same triangulating strategy on another topic (e.g., “Do vaccines cause autism?”).

Closing/Assessment: Discuss why good judgement is important in the information age.

All that from a one-sentence lesson plan.

Another Example

Let’s look at a different example: the causes of the American Civil War.

WHAT: Students will be able to identify the main causes of the American Civil War

HOW: By researching historynet.com and pbs.org in pairs using iPads

WHY: So that they can learn to settle differences and avoid war

Put together: Students will be able to identify the main causes of the Civil War by researching historynet.com and pbs.org in pairs using iPads, so that they can learn to learn to settle differences and avoid war.

Notice I left the WHY bolded—to remind us of the point of all this. Why else are we asking students to learn the causes of the war? It’s not just to know history; it’s so we don’t repeat them. So we can appreciate our ancestors’ experiences and become a better society. Learning about the things that divided people—i.e., states’ rights, slavery, and the election of a new president—will resonate with the current generation growing up in a polarized political climate.

An expanded outline for one lesson might look like this:

Opening: Ask students, “What causes fights?” Ask them to share experiences where they couldn’t resolve a conflict with a sibling or parent. Introduce the American Civil War, where brothers often fought brothers.

Activity: Students will conduct research online to find out what led to the War.

Closing/Assessment: Students will share their findings and discuss how these causes might mirror their own experiences or observations.

Concerns and Questions

1. What if I’m required to write and submit FULL lesson plans?

There is no better way to develop your lesson plan than to draft a one-sentence summary defining your WHAT, your HOW, and your WHY. It simply becomes your lesson objective. Once established, it’s fairly straightforward to flesh out, as I did with the evaluating sources example above. Remember to bookend your lesson with the WHY.

2. Isn’t the one-sentence lesson plan really just a lesson objective?

Yes and no. The one-sentence lesson plan is much more robust, because it pushes you to consider the HOW and the WHY. This makes it easier to plan your lesson opening, your class activity, and your closing. Also, having the HOW and the WHY pushes you to think from the student perspective. The traditional lesson objective doesn’t necessarily force that kind of reflection. However, an ideal lesson objective would incorporate all three elements.

3. What if I have to write lesson plans based on certain standards?

Then your WHAT is already done. I can take an 8th grade Common Core standard such as, “Analyze how particular lines of dialogue or incidents in a story or drama propel the action, reveal aspects of a character, or provoke a decision,” and turn it into a one-sentence lesson plan:

Using Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, students will analyze how lines of dialogue propel the action, which will help them understand archetypal story structures that engage readers.

Here I used a tool—the book—as my HOW. It is not always a strategy or activity. I also switched the order (i.e., from WHAT-HOW-WHY to HOW-WHAT-WHY) and used more natural language (e.g., by substituting “so that” for “which will”).

4. What if I’m having trouble figuring out the WHY?

One way is to root out the underlying idea (or theme) of the topic. For example, what is at the heart of just-in-time (JIT) operations management? Efficiency. How about the 1989 protest at Tiananmen Square? Injustice. The key is to open your lessons with that underlying theme, rather than with the strict definition. With the JIT example, you can relate the idea of efficiency to how students prioritize reading assignments—that they often read on an “as-needed” basis when the workload increases.

Another way to figure out your WHY is to search for the common human experience behind a concept. WHY, for instance, do students need to identify chemical reactions that involve oxidation? You have to get creative. What do we all experience related to oxidation? How about seeing a half-eaten apple that’s turned brown? That’s oxidation at work. Learning about it might help students understand why certain foods go bad and to avoid it (the WHY). That’s something we can all relate to.

A major reason we learn what we learn is to help us understand the world and improve our ability to judge or make decisions. Isn’t that why we learn JIT, Tiananmen Square, and oxidation?

Finally, a third way to figure out your WHY is to…Google it. Yup. Honestly, there are just too many valuable ideas online to not take advantage. I actually typed in, “Why do we study slope?” just to understand its real-world application outside of math. (I’m surprised by how often people don’t pose questions whenever they’re unsure about something. Forum sites like Quora and Reddit are perfect for this.)

Even if you can’t figure out the WHY, you haven’t wasted your time. It’s the student-oriented mentality that matters—something a traditional lesson objective does not necessarily foster.

That’s the beauty of the one-sentence lesson plan. Not only does it organize your lesson, it also puts the focus of teaching where it should be—on the students. Try it! ♦

If you found this post valuable, click here to access Dr. Norman Eng’s FREE 5-Minute Teaching Makeover—two videos designed to help you re-engage and motivate your students. Also, check out my podcast interview with Dr. Eng, where we talked about strategies for teaching college students.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Come on in!!

I have been attached at the hip with Sinek and his work this year.

I love the adoption of it with the one-sentence lesson plan.

Thank you!

Glad it helps, Shayne! Big fan of Sinek too.

How can I incorporate this method in a special needs preschool classroom?

Hey Naomi, I think the one-sentence lesson plan could for sure be used in a special needs preschool classroom. All you are really doing is identifying the content knowledge and skills you’d like to teach your students (the What), the activity you’ll use to teach it to them (the How), and the purpose for doing so (the Why). A good place to start might be taking a look at the content you’re helping your students learn. This could be a literacy skill or even a science concept. Next, select an activity that will help the student learn that skill or concept. For an example of what this might look like in an early childhood classroom, check out this comment by Joy Daniels.

Thank you very much for this edifying podcast. I find this excellent to me as a professional teacher however can you help and give another blog about leaner centered methodologies and techiniques. Thanks abunch.

How would you modify the one-sentence lesson plan, particularly the ‘why’, for different content areas, and for different stages of development?

Hi Beth, it’s hard to answer this question without specifics of your discipline. I will say that the one-sentence lesson plan is definitely flexible for various content areas. The key is to ask yourself, “Why do students need to know this?” and to relate it to something they understand or care about. Anything you can provide in terms of being more specific about stages of development, and I’d be happy to answer.

The WHY for me is the big idea that I hope my students will infer and understand; the enduring understanding. I start planning with the WHY and WHAT which reveals to me clearly the HOW (learning strategy, activity, and assessment).

How about phrasing your sentence as open questions, so that it becomes an invitation to students to think and inquire?

How can we evaluate the credibility of online sources?

How might this help us make better decisions?

I love the possibilities that the one-sentence lesson plan opens up. If it’s something teachers and students work on, then yes, opening it up to a question would a great idea. Maybe even starting out with the WHY!

You have just helped me boost my teaching to another level. I’ve always provided the “what” we are doing part of a lesson at the beginning of each class. I also know that I need to make the lessons relevant for the students, but have struggled with that somewhat since I teach an Integrated Language Studies class (teaching college students better reading and writing skills within the context of a general education class). Using this format seems to have streamlined the idea and I’m now thinking of various “whys” that I’ve never considered before. Thanks for the simple, yet brilliant idea.

Teri, love to hear that. I’ve always thought of teaching reading and writing skills as so relevant to students’ lives and sometimes they just need to “see” it. Maybe it means they can persuade others – bosses, friends, etc. So many possibilities. Let me know how it goes.

Dr. Eng,

Thank you for speaking life into what folks like myself focused on Personalized Learning have been trying to put into words. I’d love to invite you to participate with my team of instructional coaches @ksuiteach.

Would love to hear more! You can contact me from my website, http://normaneng.org.

I love this and have already put it into action. Perfect fit for my class.

Thanks, Jenn!

I just used the one sentence strategy for my first observation of the year:

Students will be able to categorize their current knowledge of the brain by building a class concept map, so that we can address misconceptions and establish a framework upon which to build new information on how our brain learns.

It really helps me see the level I am asking students to tackle.

Kristin, that is a great 1SLP–esp your HOW and your WHY. Concept maps are way underutilized and students really get engaged with it. Thanks for sharing.

How can school apply it effectively having a completely inexperienced staff without compromising the teaching level and students’ performance? Any hints? Please!

Hi Juliana! I’m Holly, a Customer Experience Manager for Cult of Pedagogy. We suggest not implementing it as a school right off the bat. Consider starting with the more experienced staff, a smaller group of people who would be able to model it for others. That core group could then model it in a PD staff meeting and practice it together. Hope this helps!

I agree with Holly. My original purpose in creating the one sentence lesson plan was to help busy and veteran professors, who just need a focus for their lesson. So experience knowing your curriculum and teaching in general would help. Train a small group (such as coaches) who can implement it in a classroom or two and then spread the 1SLP once they feel comfortable with it and see it’s helped teachers.

Hey Norman!

Really like your ‘one sentence lesson plan’ . It’s versatile and can be adopted across grades and subjects!

Thanks for sharing the examples!

Hi. I like the organization of the one sentence lesson plan. I teach PreK, ages 3-5 years old. I have core curriculum, state standards for ELA & Math to follow. Your examples are for High school lessons. Can you give an example for Preschool aged students and teaching alphabet knowledge?

Gayle, I’ve mostly used this in the secondary/tertiary level, so I invite teachers at the early childhood level to please respond if you’ve used these in your classroom! Thanks.

Hi,

We recently reviewed your approach to lesson planning at a faculty meeting. I am interested in knowing if you’ve had colleagues, or know of teachers who have used your approach in the art classroom. I’d love to see some examples!

Hey, Audra! I work for Cult of Pedagogy. Thanks for leaving this question.

Alright, art teachers–what do you think?!

I am a high school Spanish teacher who is currently starting an art unit. It is toward the end of the school year, and I have decided that I am going to pilot this in one of my preps to see if it does in fact simplify things.

Here’s my first reaction: It is harder. Why? Because it’s different. But, I am excited to see if I can do it.

I am replying, because I wanted to share my first lesson plan. Students will be able to list different forms of art by discussing in small groups possible definitions of art so that they can determine if art can in fact be defined.

The hope is that their lists will match many of the terms on the vocabulary list that they are going to receive. I understand that language goals are different from art goals, but the way I see it, if you try doing this occasionally, you will be providing a meaningful purpose for some of the things that you already do.

Hey Lauren,

Good for you — so excited to hear you’re giving one-sentence lesson plans a try – it looks like you’re on your way, and I think you’re gonna love it!

Lauren, I’m the author of this post. I love this 1SLP! It is specific and focused. Would you post this on Twitter (if you can) using #1SLP? I’m collecting a bunch. Or let me know if you have more!

Hi Audra, I am collecting 1SLP from teachers all over–if I see any from art teachers, I will pass it on!

I just saw this and I think it will suit my unique art planning needs- I do traditional teacher directed lessons eg or PK-2nd, and TAB/CBAE in 3rd-5th. I’ve been looking for a format that would work for both, and I think I just found it! I will use each question as a heading, and provide specific details, both to keep me on track as I switch between different levels throughout the day, and to make it easy for substitute teachers to teach as I would have taught when I am absent.

I’ll post links when i have some complete- maybe next week.

This also a great structure for framing goals on an IEP.

Trevor – you’re absolutely right! Truthfully, this can be used to structure almost anything that require goals–meetings, workshops, lessons. Love it.

Hello Educators,

I feel like I’m behind the eight in discovering this seamless, but educator-friendly practice. So as an educational leader, I’ve observed during discussions and reviewing teacher lessons plans that the “why” or the “so what” is omitted. Knowing the “what” (the program or curriculum said to do this), then using your bags of educational tricks

and hooks to ignite the “how” (not program, YOU), and then the “why” tells our critical thinkers where to look, but not exactly what to look for because we have a variety of thinkers. Boom! I can see this lesson plan working already. So for my early childhood educators out there here we go:

What: Students will be able to recognize how numbers are used around the school environment and outside the community.

How: We will walk around with our notepads as math practitioners and write down numbers that we discovered how they were used.

Why: So that students can recognize how numbers are used and seen in everyday places and in their everyday lives.

I hope this was helpful. I might do another post for reading, lol!

Enjoy Educators

Joy, this is great! The 3 parts are so succinct, focused, and clear. Feel free to share (and read other 1SLPs) on Twitter using #onesentencelessonplan!

Have you considered adding a language objective piece to this approach?

Hi Jamey! The great thing is that this 1SLP can be modified for different audiences. If you feel the “what” can contain a language objective other than a content objective, that’s fine. For example: “Students will be able to orally describe the properties of a polygon using at least three vocabulary terms by…”

Ms. Gonzalez,

You’ve done it again! Thank you for sharing great insights and for collaborating with such excellent teachers as Norman Eng.

Much success,

-Mr. P.

Mr. Eng my school has added to your One Sentence Lesson Plan. We now have the What, the How, the Which and the Why. The Which is was assessment tool are we going to use to measure this What. I personally struggle with this component. I prefer just the x, y and z, and leave out that additional w. Yours makes more sense, and my school’s is “confusing”. What’s your opinion on this?

Hi Carol! That’s a great question. I’ve had some people bring up the assessment issue. First off, I agree with you about the simplicity of the 3 parts–the what, the how, and the why. At the same time, assessment is important, so I understand the desire to add to the one-sentence lesson plan (1SLP). One solution is to think of the “how” as two parts: 1) “How do we reach this goal?” and 2) “How do we measure students’ learning?” However, I wouldn’t add the latter as part of the 1SLP. It simply becomes too cumbersome, which undermines the whole point of having one easy sentence.

Carol, I’m open to hearing people’s arguments otherwise, if it’s compelling. For now, I would keep that fourth element as a separate part. Do me a favor, bring back my above comment to everyone; if they can come up with an elegant solution, let me know!

I can see how this benefits teachers with planning, but what are your thoughts on having these written on boards for elementary students. Do you think this would be a valuable addition to the practice? My principal is requiring us to write 1SLP for each subject on the boards daily. Since I am new to this practice, I was hoping you could help me see the benefit to students.

This Scholastic article talks about the learning objective needing to be more than just something you write on the board and have students copy down. I think the benefit in writing a learning objective on the board is that it brings clarity to teachers and students about the purpose of the lesson. It can also serve as a springboard for discussion. Adding in language objectives can also have a tremendous impact on English language learners in content classes, as this Colorin Colorado article points out. ELL students not only hear you talk about the goal of the lesson, but also start to make associations with the words written on the board.

I love this and plan to use it with my teacher candidates as we create lesson plans. I attended one of your workshops and you shared a hard copy of the One-Minute Lesson Plan. Would you be able to share (or I could

purchase) a digital copy as well? Thanks!

Hi Rachelle! Would you email me directly? Norman@educationxdesign.com and I’ll do my best to help. Thanks.

Thanks for the logical and informative suggestions. We currently use a model that shares similarities, but it was nice to see that these methods are being encouraged.

Oh my God! This was breathing clear air! I’m an EFL teacher in Guatemala and I had many concerns about doing the planning, but now that I read and reflected on your insights, they gave me hope, thanks for that! 🙏🏻

So glad the post helped alleviate some concerns, Andrea!