Listen to my interview with Alex Shevrin Venet (transcript):

Sponsored by NoRedInk and The Modern Classrooms Project

This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

As a teacher, you probably find yourself in situations pretty often where you’re made aware of a student having needs or challenges that exceed what your school typically offers them. It might be a need for extra time or attention, a shortage of school supplies, food, or clothing, a need for transportation, a need for help with organization, structure, or time management. The list of student needs in so many schools is never-ending, and your desire to help meet them is probably pretty strong, too.

But attempting to meet these needs on your own — to become a kind of “savior” to your students — can not only lead to burnout for you, it’s also not ultimately that helpful to the student long-term.

Joining me to talk about this on the podcast is Alex Shevrin Venet, author of the book Equity-Centered Trauma-Informed Education (Amazon | Bookshop.org). This is Alex’s third time on the podcast. The first time was in April of this year, when we did an overview of trauma-informed teaching. There were two topics from her book that I thought were so important I wanted to do a deeper dive on them, so we did separate episodes for each of these. In September we talked about a concept called unconditional positive regard, a stance toward working with students that’s grounded in giving them love and acceptance without making them earn it first.

Now we’re going to talk about the danger of getting into a savior mentality when helping our students, how to tell if you’re slipping into that kind of thinking, and how to shift toward healthier and more helpful ways of thinking about and approaching student needs.

You can listen to our conversation in the player above, read the full transcript, or read some of the key points of our conversation below.

What is the savior mentality, and why is it a problem?

“The savior mentality is this mindset that teachers can get into that basically has us looking at students who’ve experienced trauma or who are struggling, and sort of taking on this feeling that our role is to rescue them,” Venet explains. “So rather than seeing that we might support them, it’s really more of this dynamic where You’re the one that needs to be rescued; I can do the rescuing. You’re the one that needs saving; I can save you.”

Why do teachers tend to think this way? And why is it so problematic?

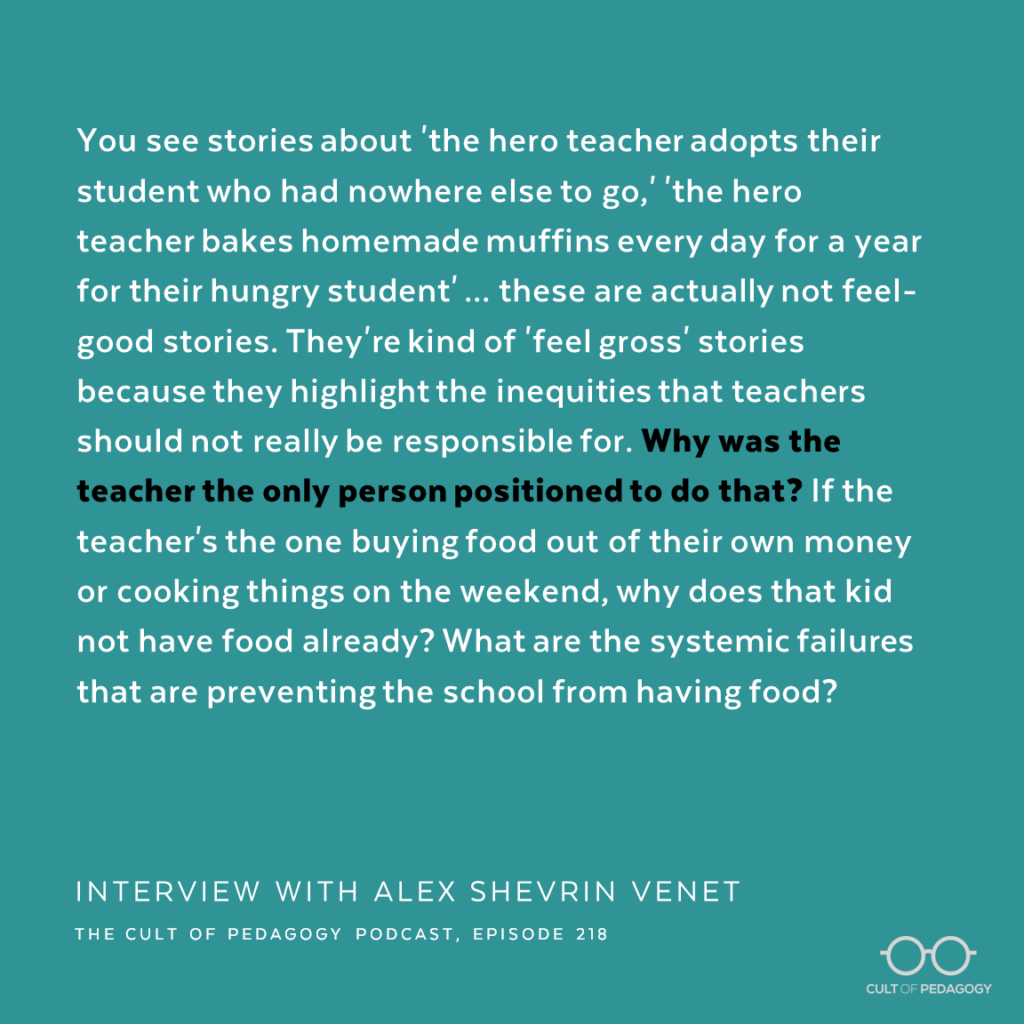

“One big reason is that our whole society tells us that we should,” Venet says. “You see stories about ‘the hero teacher adopts their student who had nowhere else to go,’ ‘the hero teacher bakes homemade muffins every day for a year for their hungry student’ … these stories are elevated but they’re actually not feel-good stories. They’re kind of ‘feel gross’ stories because they really highlight the inequities that teachers should not really be responsible for. Why was the teacher the only person positioned to do that? If the teacher’s the one buying food out of their own money or cooking things on the weekend, why does that kid not have food already? What are the systemic failures that are preventing the school from having food?”

Venet also sees the savior mentality as a way for teachers to avoid the unpleasant reality that they really can’t “save” kids all by themselves.

“When you let go of savior mentality you start to see that you’re just going to be one small piece of a student’s story,” she says. “The thing that happens in the movie where one hero teacher totally turns a kid’s life around — it doesn’t really happen like that in real life. But that’s hard because when you witness a kid who’s struggling, it’s normal to really want to help them. And to really acknowledge and sit with the discomfort that you probably are not going to fix what is harming them, it’s just really sad and hard. And so when we don’t have the time or the space to kind of feel our feelings, I think it feeds into this savior mentality because it’s just easier to go Yeah, I can fix it, I can save them. I can be the rescuer.”

What It Looks Like: Examples of “Savior” Thinking

Even if you think you don’t fit the profile of someone with a savior mentality, there’s a chance you may have had at a few thoughts that bear the hallmarks of savior thinking.

“My students with trauma are broken. I feel so bad for those kids.”

“The cultural narrative about trauma usually pushes us to one of two directions,” Venet says, “the first direction being that people with trauma are broken. You see people experiencing trauma on TV and you see them totally subsumed by flashbacks and anger and lashing out and just in a dark place. The other narrative that you see a lot is the What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger narrative, where you go through trauma and it makes you a superhero. It transforms you. But it’s really much more messy than that often. People might see some elements of growth or strength come out of surviving trauma, but they also can have a lot of struggle in a lot of hard times.”

Instead of pitying students, Venet encourages teachers to focus on getting to know them as whole people. “If we look at students and try to actually see them, then we’re not going to just feel bad for them because we’re going to know them, that they are whole and complete people, that they have skills and strengths and they’re silly and funny and they also struggle. It’s that actual building of relationships that’s the antidote to this one, rather than feeling a sense of pity, which is going to put us in a place of maybe talking down to students, lowering our expectations, not challenging them enough.”

“My students are not capable of helping themselves. I need to save them.”

This kind of thinking takes agency away from students and makes it all about the teacher instead. “People have their own strengths and capabilities,” Venet explains. “Another person doesn’t need me to survive and heal through trauma. What they do need is maybe a community of people, and if they do need something from me, maybe that’s what I can contribute to. If I’m going into that relationship thinking, I’m going to be the one to help her. I have to be this essential resource for her, I’m undermining that student’s wisdom of Who’s going to be the right person for me? What do I need from those around me? When am I ready to get help?“

“Teachers can provide the love students don’t get at home.”

“My problem with these phrases is that they make a whole lot of assumptions,” Venet says, “they often are stated when people are talking about students with behavioral challenges, students who are poor, students of color, students with disabilities, or who otherwise are the targets of bias, basically. There’s sort of this coded language around, oh, the students who aren’t getting love at home can come to school and get love. What makes you feel like they’re not getting love at home?”

There’s a difference, she says, between not loving a child and not having all the necessary resources to parent them successfully.

“There are a lot of parents who love their child so much that they work multiple jobs and therefore aren’t home to help them with their homework. There are parents who love their child so much that they come up with custody agreements to make sure that the child is in a stable place to live. And so maybe they don’t see them as much, or maybe there’s stuff around who to contact, or these things that you might see as a teacher of ‘oh, the parent doesn’t come to school,’ or ‘the parent doesn’t answer their emails’ or ‘there seems to be conflict with these co-parents’ or ‘the kid doesn’t have clean shirts that they wear.’ These are just little things, and to extrapolate and say that family doesn’t love that child is making huge leaps and bounds.”

“I alone can fix them. I can be ‘the one.'”

“People often repeat this idea that it just takes one caring adult to help a child survive and thrive,” Venet says. “And it is true that one caring adult can make a huge difference. But I think that how people sometimes misinterpret that is that any one caring adult can turn a child’s life around, or that it only should be just one person as opposed to a community. There’s sort of this individualism. Whereas what the research and experience tells us about healing is that it takes a lifetime. It takes a community. People benefit from a whole web of supportive people around them.”

She also warns against trying to provide the kind of care that we haven’t been trained to do. Even if no one else is available, she says “I still should not take it upon myself to become a counselor or a psychologist and delve into the psyche of this student. It’s not my job, it’s not my role, and I might actually be doing harm if I try, because I don’t know what you’re supposed to do as a therapist to work through that stuff.”

By positioning yourself as the only one who can save a child, you also make yourself dangerously irreplaceable. “Sometimes I ask teachers, if you got abducted by aliens tomorrow, would your school be any more trauma informed than when you were there? And if you are baking the muffins every morning, and doing a lunch group and kind of providing informal counseling for a group of students, and you are doing case coordination that really should be done by a school social worker, and then at the end of the school year you decide to move to a different school, all of those things that you are doing are just not going to happen for the next batch of students.”

“My value is in how much my students respond to me.”

When students don’t respond positively to our attempts to help them — or even push back — it can interfere with our ability to really meet their needs, because our ego takes a hit. But Venet advises us to maintain a healthy perspective on this; ultimately, it’s not about us.

“So often a person who’s going through trauma might have a response to someone that truly has nothing to do with that person,” she says. “If I’m placing my whole self-worth on Does this student trust me and confide in me and see me as their helper?, I’m already setting myself up for failure because there’s all kinds of things that are out of my control around how they’re reacting to me. If my value is about whether the student feels supported by me and healed by me and thinks I’m the best teacher ever and can come to me and confide in me, that’s placing a lot on a kid who’s just trying to live their life. I can’t look to a student to get all of my emotional needs met.

“My mentor would often say to us that whether or not your student has a good day shouldn’t determine whether you had a good day. If I had a solid plan going into the day, if I was present and responsive, if I used my tools and strategies, if I did all that I’m trained to do and used the best of my skills and capabilities, then I had a good day as a teacher, regardless of whether my students were having a hard time.”

What to Do Instead

So if we see all these pressing needs, and we’re not supposed to try to meet them ourselves, what is a healthier approach? Venet encourages teachers to put their energy into helping students find the resources they need, and when those resources are not available, addressing the systemic issues that create those scarcities.

“I encourage teachers to just be really loud about these gaps,” she says. “Your administrator might already be aware that there is a demand that’s not being met. But let them know. Every time that you want to make a referral and you feel like you can’t because there’s no availability, let them know. Write to your school board and let them know. Write to your state legislators and let them know. If teachers can collectively say, we need more mental health support, or we need food pantries that are more accessible, or whatever the need is, you’re setting that boundary and saying ‘It doesn’t make sense for me to meet this.’ If you have the time, if you have the energy, just take the little extra step and let people know we need this. We have to let folks know what those needs really are, the gaps that we’re seeing on the ground.”

Coming From a Good Place

Venet’s closing message for teachers who have fallen into a savior mentality is to be gentle with themselves.

“You didn’t create this dynamic,” she says. “This dynamic was created for you by the gross combination of cultural narratives, underfunding of schools, scattershot policies that don’t equitably meet the needs of students and teachers, and here you are in the middle of that trying to do the best you can. If you have slipped into a savior mentality because you care, don’t leave this conversation thinking that you’re doing something wrong. All you’ve been doing is trying to meet the needs of your students. What I would invite you to do is to do some critical reflection and think about, am I honoring their agency? Am I honoring their self-determination? And am I trying to make systems change so that this dynamic does not continue to repeat forever and ever?

“Caring for your students is not a bad thing. We just want to be critical about it to really support students in their self-determination.”

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

“The fact that you worry about being a good teacher, means you are already one” – Jodi Picoult

I am an indigenous learners teacher, the school is located in a far-flung area of my province, don’t have a child yet but have been babysitting my niece in any way I can. Since then I used my auntie’s instinct in dealing with my learners every day, trying to teach them the good values and behavior a good citizen should possess. And I must say in every family there is a stubborn black sheep as they say. I get mad and punish those to did bad and praise those who did right.

But as I read your blog it sank to me that those techniques were old-fashioned and very yesterday, so what I did was I let them do what they want, freely explore the world, freely say what is on their minds, and have them feel the blast. after doing do I ask them how they feel about it does it make them satisfied, do they feel fulfillment? What I did was let them repent for the consequences of every decision they made. For worrying to be one (bad/good) is what made as one (bad/good).

hope to get a reply from you Jennifer Gonzalez. I’ll be honor

Daisy, Jenn will be happy to know that the post resonated with you. I’m glad you were able to grapple with these ideas. If you haven’t already, I’d encourage you to also read the other two posts in this series on trauma-informed teaching with Alex Shevrin Venet. There are also a handful of posts about restorative justice on the site, which you may find valuable, as well. I hope you are able to continue to reflect on your stance as a practitioner as you seek to support your students.

Great episode. But, for heaven’s sake, if you suspect abuse, REPORT IT!!! It takes a child, on average, 7+ attempted disclosures before an adult clues in to what is happening and takes action. Surely we can acknowledge and address historical injustices with child protection and welfare agencies, while still protecting children from potentially dangerous situations today.