If you think school psychologists spend most of their time counseling students, think again. Guest blogger Angie McIntyre shadowed three school psychologists at work and shares the details of their days.

Caroline

Caroline works in a wealthy suburban school district, at an elementary school that houses grades 3 through 5. For the current school year, she has been assigned to work as an intervention specialist, with an intended focus on supporting students in the general education setting.

She arrives at work on time, but every last parking space in the lot is taken. A quick glance at the dashboard clock reveals two choices: She can be late to her meeting, or she can park around back in an area deemed off limits. She yanks the wheel hard to the right and takes the off-limits space, deciding it’s worth suffering the custodian’s wrath.

She hustles inside the school, hair wet, eyes tired, and throws her bag down as she greets her first customer of the day, a special education teacher. After a brief moment of niceties, they launch right into it: Two of the teacher’s new students are struggling. Not struggling in the sense that they are a little behind in reading or math, but struggling in the sense that they have severe cognitive impairments and their highly specialized programming isn’t meeting their needs. The skilled, caring teacher is out of ideas, and she needs Caroline’s help. Statements of frustration like “I shouldn’t have to deal with this,” and, “This kid should know better,” escape the typically sunny teacher’s mouth.

For the next ten minutes, Caroline’s morning continues as planned. She and the teacher discuss creative ways for keeping the students engaged, encouraging socialization and improving motor skills. It is a productive conversation, in which Caroline carefully walks the fine line of trusted adviser, sympathetic colleague, and pep-talk deliverer. The meeting will create hours of additional work for Caroline—she will have to conduct observations in the students’ classroom, make the necessary changes to their daily schedules, and follow up with multiple service providers—but she feels good about the small amount of progress the students have made thus far.

Time to make some phone calls. Caroline has been asked to start some new social skills groups, but difficulty in getting parent permission has delayed everything by a few weeks. Most parents won’t be available for phone calls at this time of the morning, but she has to give it a shot—she loves teaching the groups, and she wants to make sure they actually happen. Caroline is not naïve—she knows that teaching social skills is a daunting task, that behaviors practiced in small groups often fail to translate to the classroom. But she’s excited about a new curriculum she’s piloting, and she hopes she can teach the students how to make a friend or two.

Before Caroline even cracks the family directory, however, a second special education teacher stops by; she wants to follow up regarding a very intense meeting that took place earlier in the week, one about a student on the autism spectrum whose actions have been endangering himself and others. Although Caroline has never met the student, she was tasked with leading the meeting. Because the special education teacher has a caseload of students to manage, they agree that Caroline will take care of the administrative fallout from the meeting. After the teacher leaves for her own classroom, Caroline sighs and pulls out her laptop. It is now up to her to fix the student’s schedule, to direct the adjustments to his behavior plan, and to ensure the myriad staff members understand the changes and follow through on them.

So much for the social skills group.

Caroline’s office mate—a counselor who spends much of her time playing the role of social worker—reflects that things are particularly crazy at the school right now, due to the sharp increase of new students with highly intensive needs. In a twist of irony, another teacher arrives in Caroline’s office just then to discuss an acceleration case. The student’s family is convinced she is too bright for her classroom, and they are demanding she be moved ahead a grade. Caroline will need to call the family and remind them of the team’s decision not to accelerate the student the previous year, a decision based on extensive data.

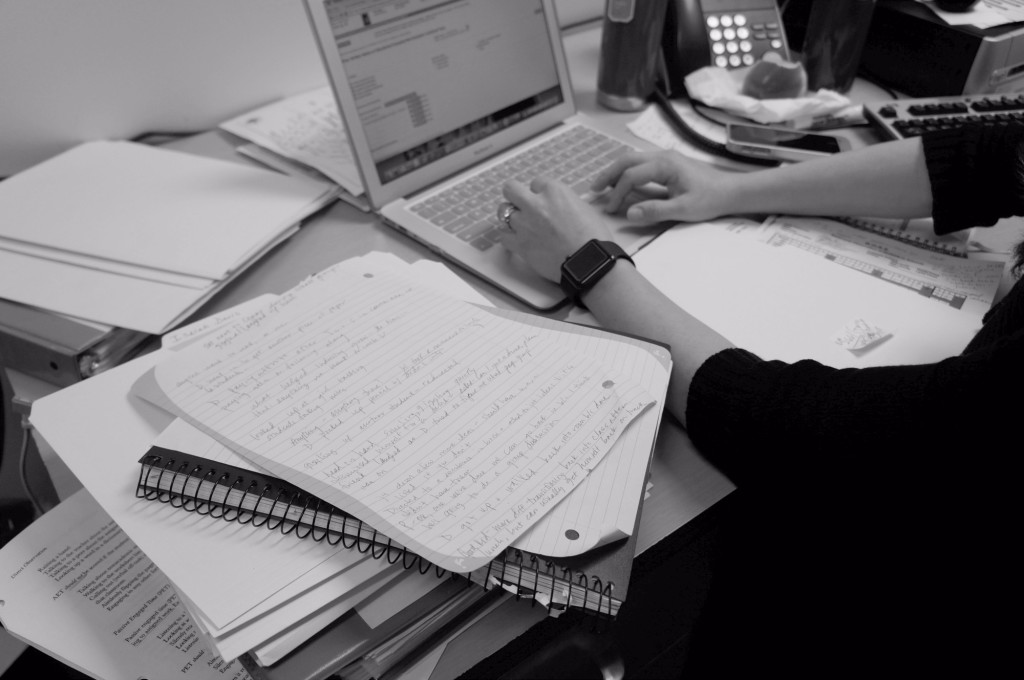

Over the next hour, Caroline hammers away at her laptop, attempting to cobble together an email explaining the plan for the ASD student she’s never met. The email should only take ten minutes to write, but Caroline is constantly interrupted. A third grader wanders in and begins rummaging through Caroline’s office, mumbling something about a broken water bottle. Teachers continue to stop by to discuss students, to search for sensory fidgets and paperwork, to ask quick questions. A student comes in to give Caroline a hug, which she readily accepts.

By the time Caroline finishes the email, she has lost a significant part of her day, as well as her opportunity for calling parents about the social skills group. But she has also accomplished a great deal—she has calmed an anxious student and set her up for a positive day. She has developed and communicated a streamlined plan that will help another student be safer and more productive at school. She has supported her friends and colleagues in their efforts, working her magic in the background so they can help the students on the front lines.

And—at the behest of the custodian—she has moved her car to an acceptable parking space.

Allison

Allison is a school psychologist in a large, urban school district whose students come from a wide variety of socioeconomic, cultural, and racial backgrounds. She splits her time between an elementary school with close proximity to a major university, and a high school located in a low-income neighborhood with a historically high rate of violent crime.

She takes a deep breath as she sifts through a thick folder of notes and assessment protocols, silently scolding herself that she hasn’t finished the report in time for the meeting. She had hoped to arrive earlier, but daycare drop-off was a bit bumpy; the baby had a blowout in her carefully selected first-day-of-daycare-ever clothes, just as her two-year-old brother melted down at the prospect of getting dressed. But like so many educators, she will have to shut out the needs of her own children and focus on other people’s kids for at least the next eight hours.

Thank goodness the elementary school is still relatively quiet. She can prepare without interruption, review the results of her testing and search for research-based interventions for anxiety. She will be meeting with a team of educators and a student’s mother to discuss the results of a complex special education evaluation. The team would like to dismiss the child from special ed and support her in other ways, a process that can be terrifying for parents. Allison has rearranged her entire schedule to be at the meeting, knowing it will require the perfect balance of data-sharing, empathy, and encouragement. She practices what she will say, checks her notes one more time, and arrives at the conference room only to discover the mother has cancelled the meeting at the last minute. Argh.

So back to her regularly scheduled day.

Allison grabs her bag and forces herself not to glance at her baby’s empty car seat as she sets off for her other building. She spends the next thirty minutes driving to the inner-city high school where she works, the one that recently made headlines when a loaded gun was discovered there. The building has no metal detectors, but Allison hopes her office’s basement location will protect her from the violence and gang activity that have been a serious problem in the school this year.

The basement locale doesn’t keep her safe from mice, however, and she shrieks as one crawls out from behind her computer. She seeks out a colleague for support, a speech/language clinician who reassures her by doing an “anti-mouse dance” and extolling the virtues of rat poison. Allison is now two-and-a-half hours into her workday. She hasn’t accomplished as much as she would have liked, but at least her adrenaline is flowing.

Next, she ventures upstairs to help monitor the hallways between classes. At 5’3” in heels, Allison is shorter than most of the students, but she does her best to seem tall and authoritative. After an incident-free passing time, she stops by the office and quietly rejoices when she finds completed checklists awaiting her. (School psychologists have to walk a fine line between gentle encouragement and outright harassment for completed questionnaires from teachers and parents; reminder phone calls, cheerful notes, verbal threats, and leftover Halloween candy are all employed regularly with varying degrees of success.) Jealously guarding the prized forms, she heads back to the bowels of the school to catch up on some email.

For the next half hour, Allison engages in an incredibly boring phone discussion about how to score an adaptive behavior assessment. It’s the kind of phone call psychologists put off because they know it will take forever and the short-term payoff will be minimal. But in the long run, the conversation will inform decisions about whether or not students qualify for extra support. And as the “gatekeepers of special education,” psychologists like Allison are expected to have this kind of arcane information at their fingertips.

Allison spends the next few minutes multi-tasking—she checks her email, keeps an ear out for emergencies on the school walkie, and gets out the old breast pump to take care of new mother business. (Allison is lucky in this regard—her basement office affords her privacy for pumping that many classroom teachers would die for.)

So far, Allison’s day has gone uncommonly smoothly. She hasn’t been called to any crisis situations, no one has popped by her office with urgent questions, and she has generally stayed on schedule. She attributes her good luck to the fact that she only recently returned from maternity leave, and her colleagues haven’t gotten used to relying on her again. She admits to herself that she wouldn’t actually mind a little urgent interruption; urgent interruptions tend to keep the job exciting and fresh.

Now Allison clicks open an email she’s been avoiding, one from a special ed teacher who works with students with significant cognitive delays. The teacher is concerned about the plan Allison helped develop for a student whose problem behaviors include swearing, threatening, and hitting staff and students. The teacher doesn’t think the expectations for the student are high enough, and says the plan isn’t fair to the rest of her students. Reading between the lines, Allison infers that the teacher is sick and tired of dealing with the kid, and she wants him out of her classroom for good. Situations like this are one of the toughest parts of the job because they force psychologists to play the bad guy. While she knows the teacher is stretched and stressed, Allison has to advocate for the student.

After consulting with one of the school’s social workers, Allison writes a carefully worded response to the teacher, validating her concerns, thanking her for her help and patience, and explaining that it will take time for the student’s behavior to improve. Taking the utmost care not to upset the hardworking, overtired teacher, she asks another psychologist to review the email before ultimately sending it off.

Because Allison’s day has been a calm one, she allows herself fifteen minutes to eat lunch away from her desk. As she scarfs down a turkey sandwich, she chats with the school social worker—her closest ally and sometimes therapist—about life outside of work. Then it’s back to her dark, educational overlord, the personal computer. In some sense, the opportunity to respond to email and work on reports during the school day is a luxury; still, Allison would rather spend her time working with kids and teachers, and she wishes she didn’t have so much pressing communication withering away in her inbox. Most of the duty day has come and gone, and she has yet to make contact with an actual student.

Next, Allison opens Google Docs to view a professional development plan she recently drafted for the team she leads. The group has adopted the lofty and potentially frustrating goal of improving interventions for failing students. Staff members at the school—like those at most schools—are frustrated with the intervention process, and continue to see it as a waste of time, a hurdle between struggling kids and special education services. If Allison’s team can solve this problem, they deserve a medal.

Allison has a few spare minutes, which she uses to write up a last-minute evaluation report. The report is a sixteen-page document chock full of data detailing a student’s strengths and difficulties, data which she and the special education team have collected over the previous six weeks. While her job includes a heavy load of special education evaluations and reports, Allison often puts such tasks off in favor of more urgent ones. As she types, she briefly wonders whether this particular report will make any difference in the life of the student. Then she shakes her head and reminds herself that all the data collected, all the progress monitored, and all the time invested are a psychologist’s way of ensuring students get the service and support they so desperately need.

Allison’s heavily administrative day ends on a positive note, at a staff meeting where the principal addresses the difficult climate at the school. While she expects this meeting to be depressing and frustrating, Allison is struck by the new principal’s willingness to listen and respond to staff concerns; she also appreciates his admission that he has made mistakes in his handling of the situation.

The meeting ends, and Allison takes a moment to reflect that she has just finished a pretty good day’s work. She has laid the groundwork for the next few weeks: Now reports can be written, interventions implemented, and the school may even be a little safer. Still, she wishes she had gotten in some face-to-face time with students and teachers.

Before packing up and heading out, Allison takes a quick peek at her schedule for the next day, and she smiles to herself. Tomorrow, she sees, will be a people day. Tomorrow, she will chat with a favorite student about his post-high school plans. She will help another student address some problems she’s been having with anxiety. She will consult with her favorite team of teachers about building bridges between school and home for struggling students.

Tomorrow is the reason she became a school psychologist. Tomorrow will be a good day.

Justine

Justine practices school psychology in a medium-sized school district in a first-ring suburb. She splits her time between early childhood education and an alternative high school (AHS), both of which are housed in the same community building. Justine’s students are representative of the school district, which includes a wide range of socioeconomic, racial, and cultural backgrounds. The AHS also houses a large population of recent refugees with limited English proficiency.

Justine throws open her office door at 7:30 am, barely registering the creepy, life-sized doll perched on a chair and half-covered by a stack of files awaiting review. The doll sports a hooded sweatshirt, jeans, and a castoff pair of tennis shoes, and Justine’s office mate—a special education teacher who uses humor to stay positive in a tough work environment—has taped a picture of his own face over the doll’s. Justine would like to return the favor with a prank of her own, but today’s schedule won’t allow for it.

Justine supports two very different populations from this office: young toddlers and preschoolers just starting on their educational paths, and near-adult students hoping to eke out a diploma. Today is technically an AHS day, but Justine will likely engage with both settings, as she usually does. The only thing separating Justine’s babies from her big kids is a flight of stairs, which doesn’t provide much of a buffer between the two worlds she serves.

She begins by answering a few emails, items that have piled up overnight. As she scans her inbox, Justine reflects on a recent NPR article about the healthy work/life balance in Denmark, and briefly contemplates moving her husband and two young children to Copenhagen. Maybe next year.

Leaving a few unanswered emails for later, Justine heads to a meeting for one of education’s hottest initiatives—Positive Behavior Interventions & Supports (PBIS). For most school employees, PBIS is both a blessing and a curse—it requires a great deal of work up front, but it can do wonders for school climate and morale when implemented correctly. As the psychologist for the alternative high school, Justine leads the PBIS team. At today’s meeting, she presents her colleagues with the data for office discipline referrals. The purpose of the data is to celebrate successes and target areas for improvement, but the teachers—battle-hardened and stretched thin—are struggling to stay positive today. Instead, they use the meeting as a venting session about student behavior. Justine gives them some time and space to share their frustration; then she tries valiantly to get the meeting back on track. During her ten years of practice, she has learned that admiring a problem rarely solves it.

After the meeting, Justine finds a student waiting for her in her office. The student says she is pregnant, and claims she is bleeding because her mother kicked her that morning. Concerned for the student’s health and safety, Justine calls the police and explains the situation. When the police and ambulance arrive, the student makes excuses for her mother and declines to press charges. However, Justine informs police that the student has been in similar situations before; this will ensure that a domestic violence counselor meets with the student when she arrives at the hospital. After the emergency workers leave with the student, Justine updates her colleagues and completes the paperwork required by the district in such situations. By the time she finishes the work, she has invested two hours of her day into the unexpected crisis. While student emergencies happen with lightning-fast speed, responding to them is often slow and grueling work.

She attempts to get her day back on track, but is quickly thwarted by an early childhood special education (ECSE) teacher who needs help. Justine listens as the teacher describes a student who has been hitting, kicking, and biting her peers, and suggests a team meeting with the child’s service providers and family. Justine spends most of her early childhood-related time engaging in these types of conversations, or in evaluating children for special education eligibility. She would like to engage in more proactive work with the early childhood students, families, and staff, but crisis management always trumps prevention.

There is never enough time in Justine’s workday. To deal with the time constraints, she plays a little game called “Move the stuff around on my calendar.” Staring hard at her computer screen and clenching the mouse, she gives a caustic giggle and murmurs, “Drag, drop! Drag, drop!”

Justine begins her designated period of processing, during which she talks with AHS students sent to the office for low-level offenses such as work refusal and technology use. The period ends abruptly when a teacher calls for help with a student who is screaming curse words at her in the classroom.

Justine coaxes the student into her office and talks through the situation with her. Because the student is a recent refugee with limited English,

Justine calls a cultural liaison for additional support. With the help of the liaison, Justine manages to calm the student enough for her to finish her day at school, avoiding suspension. Justine reasons that the AHS classrooms would be virtually empty if the students were suspended every time they swore.

At 1:45, Justine finally manages some time at her desk, reviewing one of the files perched on the creepy doll’s lap, responding to email, and cramming in a little lunch. The rest of her day is a mix of dealing with office referrals, supervising the hallways, responding to emails, and filling out forms.

Justine admits to herself that her workday never goes as well as she wants it to, that her work rarely rises to the level she expects from herself. In addition to time constraints and the bureaucracy of special education, Justine and her colleagues face near-insurmountable obstacles like racism, poverty, disability, and chemical use.

But during the course of her jam-packed, unpredictable day, Justine knows she has actually accomplished a great deal. While the payoff may not be obvious today, her hard work and dedication will make a difference. Because of today’s efforts, a vulnerable young woman now knows that someone cares about her safety. An angry, marginalized student has managed to finish her school day instead of being kicked out once again. A team of specialists has made plans to come together in support of a young child crying out for help.

Though she forgets it sometimes, Justine is passionate about school psychology, and she’s pretty darn good at it.

Copenhagen will just have to wait. ♦

Join the Cult of Pedagogy mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration — in quick, bite-sized packages — all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. To thank you, you’ll get a free copy of the e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading!

This was great! I’m our district’s SLP and our school psychologist is such an important part of our team. This article sounds a lot like our psych’s day. This article is a great response to people who think that all school psychologist’s do is test kids. Well done!

Thanks, Christine. I think Angie did a wonderful job here.

Does it occur to anyone else, that we spend more time documenting than doing?

Yep. This definitely illustrates that, doesn’t it? I wonder if anyone out there is working on streamlining the documentation process so more ‘doing’ can happen!

As a School Psychologist for over 15 years this blog made me laugh as I seen the reflection of my own days and often nights at home working but it also made me cry!! Cry as I know there are so many of us out there doubting our career choice… I often wonder if I do make a difference?!?

Great article. As a special education teacher in Australia, this is a similar process for those in positions such as Head of Special Education Services in schools. Special education teachers will also take on some of these roles within schools, such as writing behavioural intervention plans, leasing with mainstream teachers to support students with special needs in their mainstream classes. It is an extremely important role within a school and without all the hard work that school psychologists put in each day, most of the students wouldn’t have anywhere to turn.

I was a School Psychologist for over 20 years, in three different states. I had responsibility for many of the functions described, but the majority of my time involved teacher consultation, student observation, student evaluation and conferences with parents and teachers. It didn’t leave much time for writing comprehensive reports. This had to be done in the evenings. It was pretty demanding, but I loved every minute of it, and have never regretted making that choice as a career. Since retirement, I have missed it greatly!

Hello, my name is Courtney Murphy. I am interested in becoming a school psychologist. Since you have a lot of experience several states, I was wondering if I could get your email to ask you a few questions?

I am a retired SLP (30+ years working in public schools). Over my career, I have counted the school psychologist as one of my best friends. He/she has been a confidant, a highly appreciated colleague, and often a shoulder to lean on. This article demonstrates the extremely valuable but often under-appreciated role that the psychologist plays in our schools. Thank you for a great article that should remind us to thank our co-workers for the important work they do each and every day!

Thank you for your positive comments, as a school psychologist I sincerely appreciate the acknowledgement of being there for colleagues as well.

I feel the same way about my SLP’s…we must be cut from the same piece of wood 🙂

This should be required reading for every graduate student in school psychology AND every classroom teacher! The author so respectfully nailed both the “what we do” and the “how we feel about it”, including tough daily choices about how we spend our limited and stretched time–and the bigger thoughts about whether we should continue in this field at all. Thank you both so much for sharing!

This was a great read! I just got accepted to a school psych program for the fall, and I’m both excited and very anxious about what the future holds!

We are in the same cohort ! How are you handling it so far ?

Not to be a downer, but if “Caroline” arrive at work and all the spots are taken, is she really “on time” and why is her hair wet? I am a person who struggles with time management, but I have found as a teacher, if you are at school “on time” you are late. I actually did get my Master’s in School Psychology, but I ended up using it as a starting off to get a Special Education certification because I think the most rewarding part of education is actually seeing students every day. In my opinion a lot of school psychologists are spread too thin to make a real difference and i\end up doing just what the articles said, crisis intervention, and waiting around for meetings that never happen. I found that to be quite frustrating.

Penny, you nailed it. The article was indeed very *creative*. There isn’t much accuracy in what any of their average day is like, and if one of them can’t get it together enough be truly be “on time” in order to get a parking spot, and not be behind everyone else who has already begun working, well, it sounds like that someone might be a bit of a slacker.

A school psych’s job is primarily paperwork (*administering* tests and providing the Behaviorist with the results so the BCBA can create a plan). That’s why several folks here have mentioned that “there’s more paperwork than doing”. There’s very little, if any, clinical skills being used, unless you get your license and do private evals, which is the direction I would urge anyone obtaining any degree in this field to head in.

This article is unfortunately, a fairly inaccurate picture of their job. However, it’s on the Internet, so it must be true, right? 😉

this is awesome! i’m a second year student in a school psychology program and seeing this post has made me more excited to go into this field! thanks for sharing!

I’m so glad to hear it, Alexandria. Good luck with the rest of your program!

Hello,

I’m a undergraduate student looking to get into this career path as well. I was just wondering, since you’re a grad students (or were), what kind of steps did you take to get into a psychology program ?

The articles are fairly accurate. I’ve been “psyching” for 25 years. In the beginning I was basically a psychometrician, then came ADHD and now Autism. Evaluations are more and more comprehensive and of course time-consuming – if you perform a thorough evaluation. Trouble is admin may listen to your additional work demands but unfortunately not much gets done in terms of hiring additional resources. So as demands increase something has to give… and that means some of the quality of the evaluation is going to be negatively affected. The number of evaluations are increasing and the time to perform each is increasing more and more as additional investigation, assessment, parent interviews, report writing and educational planning. This was the first year I was “blamed for not doing enough” and I wasn’t the only one. Test and consult all day, write reports at night and on weekends as the demands continue to grow and grow and the numbers… they increase. Don’t get me wrong, I like my job it’s just that the expectations are becoming unrealistic and the level of job satisfaction is decreasing for me and many others I talk to. A few years ago I started a “blue collar” business of my own and within 3 years I was making more money in a month than an entire school year as a psychologist. Honestly, the job demands of psyching far exceed those of my side business and it pays considerably less. Why do I stay? Because I feel like I make a difference and believe I am good at my job. How long will I continue to stay? That depends on how thin admin stretches me, blames me for not peddling faster in lieu of actually with the situation as a resource allocation issue. I’m quite certain admin doesn’t realize the money we are paid for our skill set isn’t commensurate with our level of education and job responsibilities. IMHO, the profession needs more school psychologists in order to serve students and families better and not be constantly rushed through evaluations, reports, consultations, etc. Would I recommend to myself 25 years ago to choose this route again?

The articles are fairly accurate. I’ve been “psyching” for 25 years. In the beginning I was basically a psychometrician, then came ADHD and now Autism. Evaluations are more and more comprehensive and of course time-consuming – if you perform a thorough evaluation. Trouble is admin may listen to your additional work demands but unfortunately not much gets done in terms of hiring additional resources. So as demands increase something has to give… and that means some of the quality of the evaluation is going to be negatively affected. The number of evaluations are increasing and the time to perform each is increasing more… and more as additional investigation, assessment, parent interviews, report writing and educational planning are required. This was the first year I was “blamed for not doing enough” and I wasn’t the only one. Test and consult all day, write reports at night and on weekends as the demands continue to grow and grow and the numbers… they increase. Don’t get me wrong, I like my job it’s just that the expectations are becoming unrealistic and the level of job satisfaction is decreasing for me and many others I talk to. A few years ago I started a “blue collar” business of my own and within 3 years I was making more money in a month than an entire school year as a psychologist. Honestly, the job demands of psyching far exceed those of my side business and it pays considerably less. Why do I stay? Because I feel like I make a difference and believe I am good at my job. How long will I continue to stay? That depends on how thin admin stretches me, blames me for not peddling faster in lieu of actually dealing honestly with the situation as a resource allocation issue. I’m quite certain admin doesn’t realize the money we are paid for our skill set isn’t commensurate with our level of education and job responsibilities. IMHO, the profession needs more school psychologists in order to serve students and families better and not be constantly rushed through evaluations, reports, consultations, etc. Would I recommend to myself 25 years ago to choose this route again? I’ll let you answer that question.

What location did you do most of your work (city, state)? I ask because I’m about to enter a Master’s program for school psych in SoCal and I’m having a lot of second thoughts on it because of like the things you mentioned, etc. Thanks.

Don’t do it. And if you do make sure you have a back up plan like MFT or clinical psychologist. Every year the demands increase but the resources don’t.

Thanks for sharing this. Seeing how school psychologists move from school to school and have to adapt their work for different students and situations is interesting. It really shows how hectic and strenuous day-to-day work in school psychology can be.

As an aspiring school psychologist, this post really helped me gain some perspective on the various types of work school psychologists engage in. The profession is not simply about counseling students (although that can be an integral part), it’s about creating a healthy, goal-oriented, and success driven learning environment for all students, whether they are struggling or not. Thank you for sharing these stories!

I stopped reading after ‘Allison’s’ story for a number of reasons. The most important reason is implicit bias. The simple fact that she works in an inner-city school seems to have her act on stereotypes and not on substantiated evidence of danger. Given the current culture, mass school shootings happen more in suburban schools and the individual behind the trigger is often a white male. Allison’s walk in an authoritative manner will not win her any points with the youth. I’m certain they know she does not want to be there. I really hated how the story made it seem like her life was in danger and that life as a school psych can be stressful simply for having to take on the duties in the inner city. With attitudes such as Allison’s are you truly there for the youth? Or is it a particular group of youth who share similar physical features and socio-economical background that receive genuine professional care?

Reketta,

You’re absolutely right. This article is complete fiction unfortunately. I’m more concerned than most at it’s depiction of the position. Many schools have discussed outsourcing this position because of their claimed “limited value”. Unfortunately, that limited value is because most school psych’s are handicapped by the school system, where we’re relegated to having kids take tests, and we practically hand over the results for others to interpret and configure a plan.

If you’re in or going into this field, for some reason, get licensed, and do private evals. If you just want to push paper all day, but still get a pension and benefits, but no respect, then this is a great place to be.

MtM

My comment will not be popular here amongst the positivity for School Psychology. I recently resigned from my position after 15 years. And a total of 30 years in public education. I’m nowhere near retirement age yet the work of a School Psychologist isn’t something I can do any longer. I am a cash cow for writing reports that bring in federal funding. With a shortage in my state, I have little time to do mental health work, curriculum development, classroom interventions. And even if I tried, the push back from administration and department heads to allow me to have a voice feels like a hostile work environment.

I have an NCSP and other specialized certificates and so much training that I feel like a walking encyclopedia of school reform. And yet I’m not utilized for anything but testing and placement for Special Education. NASP recommends a 500-700 case load. I have 1200.

I’ve served on my state board, presented at conferences, tried to do inservices for my own staff. But it’s like beating my head against a brick wall. Best practices aren’t even something people want to discuss. And so the stress of trying to be more that a tester has really done me in.

Trisha, ugh…this made me really sad, especially since I’m sure you’re not alone. The demands of testing and written reports are taking away from much of the real meaningful work that needs to get done and it’s absolutely draining. It sounds like you went to bat for as long and as hard as you could.

I deeply regret becoming a school psychologist. Our district has a 1:900 ratio, but it covers the district, not the individual school psychologist. While I serve a high school with 1300 students and the alternative high school with 100 students, other psychs in the district serve one elementary school with 400 to 500 students. They get to go home at the end of the day. I am usually at work until 7 or 8 PM. Admin doesn’t care. The union doesn’t care. It’s awful. I would quit if I could, by my circumstances don’t allow it. In addition to the traditional test and write duties of a school psychologist, I have so many other duties, and I seem to be the only one in the building who knows anything about special ed. However, if admin or teachers don’t like what I tell them, they basically attack me and then go to our director to try for a different/better response. If she says the exact same thing I said, they accept it totally and completely. Yes, it’s a horrible job. Maybe it’s just the district I work for. I don’t know.

Sandra, This is really disheartening to hear. I’d like to think it’s not like this everywhere — it shouldn’t be this way.

I deeply regret it too. My current ratio is me to 1700 kids. Can’t do it anymore.

Trisha,

I am only on my 6th year of being a school psychologist and I am finding the same exact thing. There is a huge disparity of what we are trained to do and what we actually do. I am tired of it all. We are spread so thin. How it is possible that I am feeling burnt out after only 6 years?? In my spare time I am finding I’m looking for other jobs or masters programs in a different field. It’s so frustrating.

I appreciated this article and reading through the comments of experienced School Psychologists. It’s something I am/was considering studying as I’m enrolling in my first year of community college now, but this gave me more insight into what it’s actually like. I know I’m deeply passionate about advocating for mental health, but I’m thinking teaching or becoming a school counselor may be more aligned to what I’d feel more fulfilled by at the end of the day. We’re lucky to have you all, I wish the situation was different. I don’t know if it’s making me feel driven to try to go into this field and help advocate for change or feel like I could be better off pursuing something else…

I hear ya! There’s a complete lack of respect for the school psych position, and honestly, that’s what burdens folks more than any workload. If you even had a 1:2000 ratio, it could be fine if the system respected the potential value of the position enough to allow it to be even slightly clinical. However, without a license, that just won’t happen. So, you push paper all day, and hope for retirement day, and that in between, you’re never forced to utilize the skills you’ve now lost from lack of use.

I’m about a year from becoming a school psychometrist. Knowledge is power.

I’ve been trying to figure out what I want to do with my life. Even though I’m not even technically a tenth grader yet, I know I really want to go into psychology, and ever since I found out school psychology was a thing, I was really interested in the field. I was doing some research and I found this, and I’m really glad I did. It offers a realistic perspective on what being a school psychologist is like and I know what I want to do with a potential psychology degree now. Thank you!

The blog post “Confessions of a School Psychologist” is a great read for anyone interested in learning about the challenges that school psychologists face in their work. I appreciated the honesty and transparency of the author in describing the complexities of their job, from navigating bureaucratic systems to helping students with mental health issues. It was interesting to learn about the various roles that school psychologists play in schools, and the importance of their work in supporting the academic and emotional needs of students. Overall, this was an insightful and informative read that sheds light on the vital work that school psychologists do every day.

It’s inspiring to see how Caroline is dedicated to making a positive impact on the students she supports. Her role as an intervention specialist is crucial in ensuring that all students, regardless of their needs, receive the attention and assistance they require to thrive in the general education setting. It’s evident that she not only brings her expertise to the table but also her compassion and commitment to each student’s growth.