Listen to my interview with Pernille Ripp (transcript):

Sponsored by Kiddom and simpleshow videomaker

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

If I had to pick one thing that makes the biggest difference in the quality of any person’s education, the quality of their life, really, it would be reading. And I’m not really talking about basic literacy—not about the ability to read—I’m talking about reading for pleasure, to satisfy curiosities, to understand how people work and find solace in knowing we are not the only ones who think and feel the way we do.

That kind of reading.

But when I see what my kids do in school for “reading,” it doesn’t really look like reading. I ask them what books they are reading in school, and a lot of times they give me a blank stare. What they do in reading, they tell me, is mostly worksheets about reading. Or computer programs that ask them to read passages, not books, and answer multiple-choice questions.

Knowing this has bothered me a lot, and it led me to Donalyn Miller’s book, The Book Whisperer, and then to Kelly Gallagher’s book, Readicide. Both of these books show us that the reading programs and activities schools are using don’t work very well to raise students’ reading proficiency, especially if they take the place of real interactions with real books. And they certainly don’t do anything to turn our students into people who love to read.

The only thing that can do that is books. Reading actual books alongside other people reading actual books.

What baffles me is that this message still hasn’t reached so many schools. Schools are still shelling out thousands of dollars on expensive programs, putting pages and pages of passages and comprehension questions in front of our kids every day, sending them through the system without ever having them read a real book. Just excerpts. Just passages. Just reading-related “activities,” but little to no time with actual books.

So today I’m going to do what I can to get the message out there by having my friend Pernille Ripp on the podcast. Pernille is a seventh grade English language arts teacher in Wisconsin. She has been blogging for years, she speaks all over the country, and she has written several books about teaching.

Pernille Ripp

Her most recent one is called Passionate Readers, where she writes about her own journey from teaching reading through programs and activities to teaching in a way that honors books and develops a love of reading in every child. It’s an awesome book. The best thing about it is how transparent Pernille is about her own doubts and struggles in this process.

In our interview we talk about why she made the change, what her reading instruction looks like now, and how other teachers can change their own practices. The key takeaways are summarized below. You can read a full transcript of our conversation here.

What’s Wrong with the Way We Teach Reading Now?

In many classrooms that are feeling the pressure of high-stakes testing, instruction tends to emphasize what researcher Louise Rosenblatt called efferent reading, the kind of reading we do when looking for information, as opposed to aesthetic reading, which is done for enjoyment. Reading for information is a vital skill—without the ability to tackle challenging texts, locate evidence to support claims, summarize important ideas, and identify bias, students’ academic progress will be stunted.

Unfortunately, our push toward developing close reading skills has had collateral damage. In far too many schools, reading for pleasure has been treated as an afterthought, something we encourage but don’t really make time for. Instead of giving students time to read, we’re giving them activities, projects, computer programs, reading logs, and worksheets that detract from actual reading.

“We’re constantly reading for skill,” Ripp says. “We’re constantly asking kids to do something with their reading, and then wondering why they’re choosing to leave us and never picking up another book. They can’t wait to get out of school so that they don’t have to read.”

When she criticizes these practices, Ripp has no desire to teacher-bash. “I get it,” she says. “We are all kind of facing the pressure of our districts and our government and our testing and our parents and everybody’s focus on the data to show that these children can comprehend and compete with this global market economy that we’re a part of.”

“But unfortunately,” she explains, “what that has led to is just this further step away from what we know works within reading instruction.”

Even when we do have students read for enjoyment, we require evidence—reading logs, book reports, quizzes—to prove that the reading actually happened.

This was how Ripp taught for several years: “It was exhausting,” she says. “When we did book clubs, it was all about me, and I was reading five different books and coming up with all of the questions. All the kids had to do was show up, read aloud. There was no discussion about which book we were going to read or anything like that. It was just all teacher-centered, all the time, book reports just to prove they had read rather than doing meaningful work after they had finished the book.”

The Catalyst: What Caused the Change

Then one day a student said something that stopped Ripp in her tracks.

“I was doing the ‘reading is magical’ lesson that I think we all do at some point in the beginning of the year, and a kid in front of me whispered to his friends, ‘Reading sucks.’ And you know, I wanted to jump on him and be like, ‘Oh, you just haven’t found the right book,’ because how often have we said that?”

Instead, she asked him to tell her why.

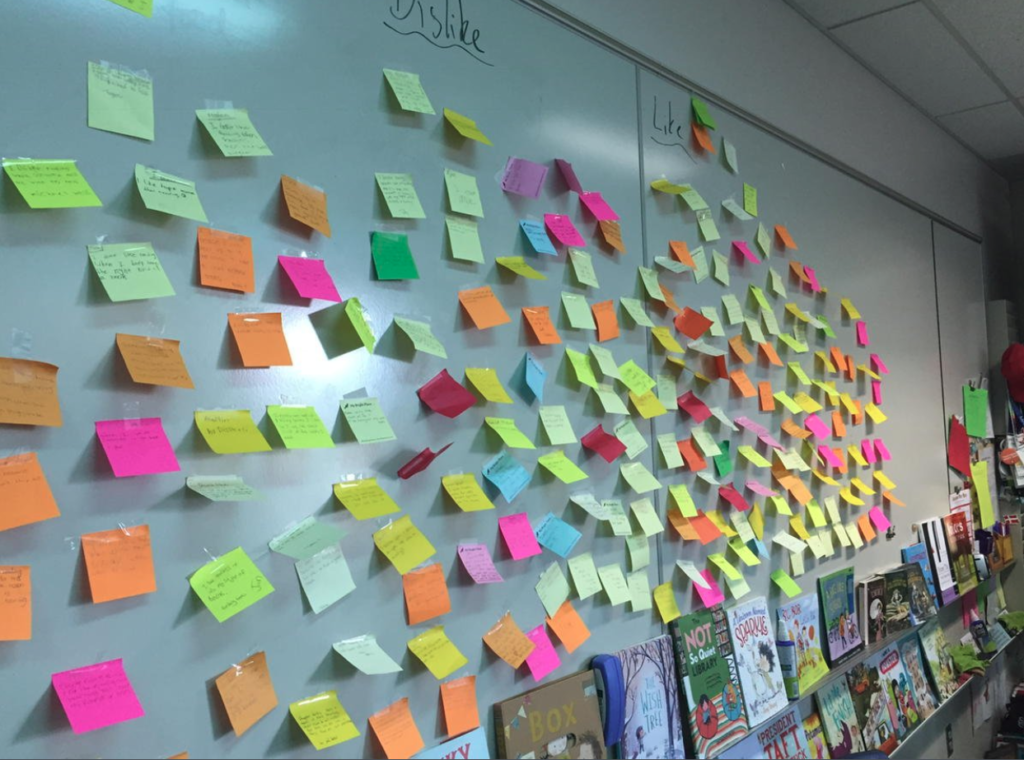

Every year, Ripp invites students to share their thoughts about what they like and dislike about reading on Post-its.

That’s when the floodgates opened: Invited for the first time to honestly share their thoughts about reading, students told Ripp that they didn’t like having to sit still. They wanted to be able to choose their own books, rather than being limited to a certain level. And more than anything, they hated the fact that every time they read something, they had to do some kind of activity related to the reading afterward.

Thus began Ripp’s journey toward what she calls a common sense approach to reading.

Returning to a Common Sense Approach

Once her eyes were opened, Ripp found herself drawn to the people she calls the “pioneers” of a type of reading instruction: Nancie Atwell, Donalyn Miller, Penny Kittle, Kelly Gallagher, Kylene Beers, Stephen Krashen, and so many others. She began to understand that scripted programs and reading-related activities—teacher-centered reading instruction—were not the way to help students become life-long readers. Over time, she shifted to a different approach.

When she talks about her current practices, she emphasizes over and over again that this is nothing new. “We have so many years of really great reading research out there, and yet it seems to be forgotten.”

Here are the most important components of Ripp’s reading instruction the way it looks today.

Time to Read

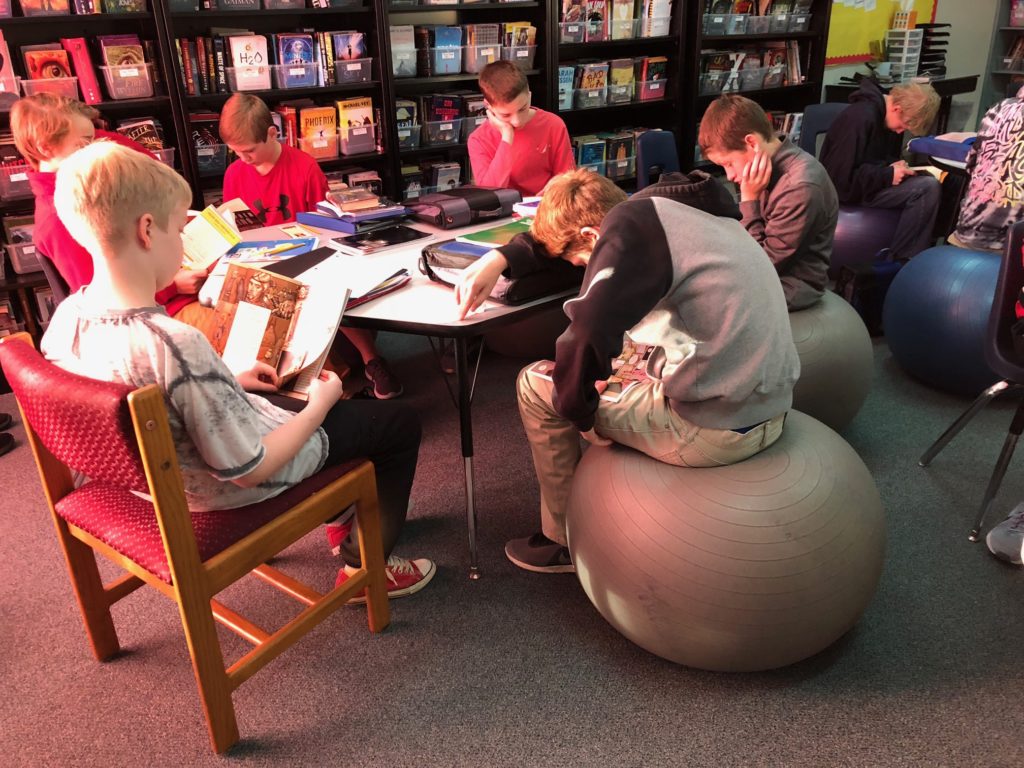

Ripp’s students are given ten minutes at the beginning of every class period for independent reading. “Every child, every day,” she says. Even though she only has 45 minute blocks with each seventh-grade class, she makes sure they get that time to read every day. “It is sacred time,” she says. When she taught at the elementary level, she was able to give students 30 minutes a day, but she no longer has that luxury.

During that independent reading time, Ripp does check-ins with students. “I’m sitting down and I’m simply saying, ‘What are you working on as a reader?’ And it gives me that two-, three-minute connection with a child if they need to book shop, if they’re not doing well, to see what their reading identity is, where are they on their journey, and then I kind of pull all this information to think about what I still need to teach them (during the other part of class time).”

Students are not graded for this reading. “We can’t actually grade their independent reading, because that’s practice,” Ripp says. So there’s no other work associated with that time: no worksheets, no logs, no written reflections. “Nothing to do except to read. I want them to fall into the pages. I want them to reach flow. I want them to be silent and in this moment of their book.”

Ripp uses the remainder of the 45-minute period to have students work on the other things you’d expect to see in an English language arts classroom. “When they come back to me (after the ten minutes), we then do a mini lesson on reading or writing or whatever it is we’re doing, 10 to 15 minutes. And then they go and do something, and that’s where I assess them.” But those first ten minutes are always, always devoted to independent reading.

Choice

“Whenever I ask kids,” Ripp says, “‘What’s the one thing you wish all teachers of reading would do?’ (they say) ‘Choice.’ And yet, what do we do time and time again? We take away choice from kids, especially kids who might not be where we would hope they would be at this time. We end up with these limited choices for them, and then we wonder why they’re the ones that distance themselves from reading the most, because they never get to develop their reading identity. They never get to go through the selection process. They never get to just read and struggle with text and have meaningful conversations and sometimes yes, make the wrong choice.”

Students in Ripp’s class always have free choice of what they want to read during independent reading time. Through lots of conversations, students practice getting to know who they are as readers so they can make choices that work for them. “They’re constantly evaluating their book choices just either through conversation or self reflection or just their habits,” Ripp says.

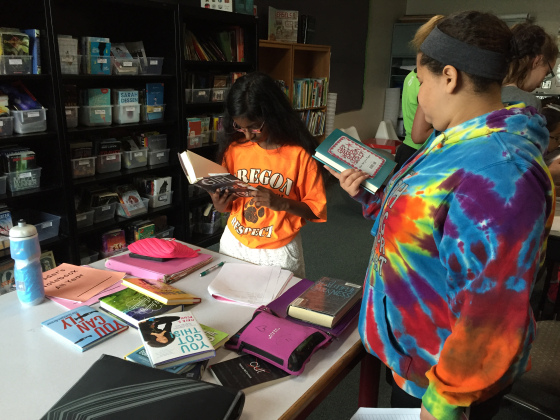

Students go “book shopping” for their next read.

If a student finds that a book just isn’t grabbing him, he is free to abandon it. “We should be celebrating when we abandon a book,” Ripp tells her students, “because we know ourselves enough as a reader to know that this will not provide us with a reading experience that will matter to us. And we need to start building up that stamina, so we need books that work for us at that time, and that’s really important for my students to remember, and to know and to recognize that what they need at this moment might be different than what they need a month from now.”

A Robust Classroom Library

Ripp’s classroom library houses several thousand books that students can check out at any time. You read that right: several thousand.

Why so many? “I need a book for every reader,” Ripp says, “and I teach kids that read from about a second grade level to a college level. I teach kids with lives that share no similarities at times and others whose lives are very much like my own. And so I need to make sure that every child has a chance of finding a book that will speak to them.”

Where do they all come from? “(At the time I had) three kids at home, you know, on a teacher’s salary,” Ripp explains. “I can’t go out and spend thousands of dollars on books, and my school didn’t have a lot of extra money, but I would rather that a child can go up to this bookshelf and find a high-quality book pretty much any time they go there rather than have to dig through the junk and hope they find something. So it just became my mission that instead of buying things to make our classroom prettier or anything like that, I bought books. I used Scholastic, I went to library sales and parents donated books, and I was always really picky. It was big for me that the books were good, and then I just purchased books.”

Why not just have students use the school library? Ripp believes students need both. “Kids need to see the books staring at them at all times, and I think that has made the biggest difference for some of my kids who would go through the motions of going to the school library and they would even check some books out, but then when it came down to actually sitting down and read it, they didn’t feel that same need or urge to read it.” Her experience has proven the research that says students read more in classes that have good classroom libraries. “I had a seventh-grader come back to me my first year at the end of the year,” she says, “and he said, ‘You know what made the biggest difference? The books were always right there staring at me.'”

Ripp’s classroom library also includes an incredible assortment of picture books. Having lots of picture books in the classroom helped remove the “babyish” stigma many middle schoolers attached to them. “If you walk into our classroom, yes there’s all those books, the chapter books and all of that, but then all around us are picture books. And it’s just a vibe, right? You feel it when you walk in that this is a classroom where you can have fun and where you get to read and you can choose whatever you want. No one cares what you’re reading in our classroom, because you can pick up picture books at any time.” To start building your picture book collection, take a look at the tons and tons of recommendations for picture books Ripp offers on her website.

Culture and Community

A constant thread that runs through Passionate Readers is the sense that a classroom culture is constantly being built, that every day, Ripp communicates how incredibly important books are to a good life, and how, if we get to know ourselves as readers, and have lots of conversations about our reading, we’ll really get to experience the true magic of reading.

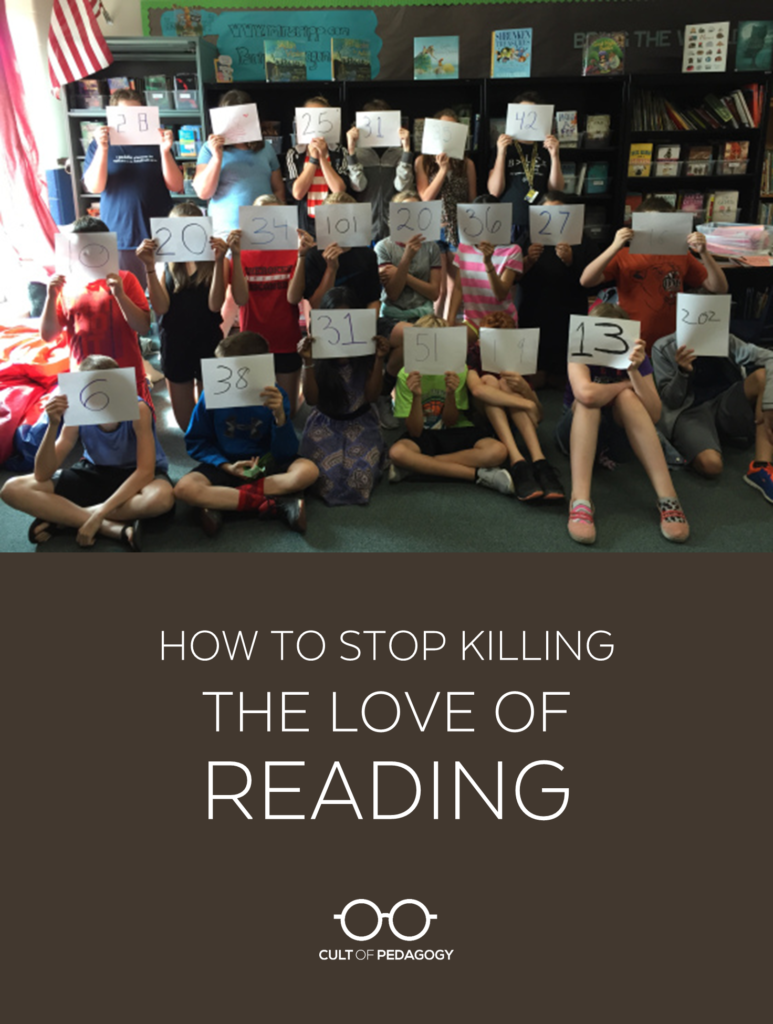

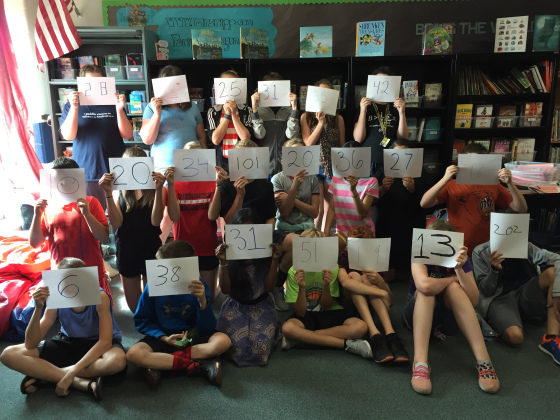

Every year, students are challenged to create their own reading goal based on their unique needs. Each student picks his or her own number of books to read by the end of the year.

The 7th Grade Book Challenge is one way she encourages students to build more reading time into their lives. This was adapted from the 40-Book Challenge introduced in Donalyn Miller’s Book Whisperer. Ripp participates in the challenge herself, just one of the ways she shares her own reading identity with her students.

Outside of things like the challenge, the culture is ultimately built on a day-to-day basis. “Teaching reading is not supposed to be quick and easy,” she says. “It’s supposed to be about human connection. It’s one conversation at a time.”

She admits that this new way of teaching is not perfect, and she’s constantly reflecting on how she can do better for her students. “We cannot go in there and expect every child to change, but we can go in there hoping that we can help,” she says. “I tell my students this: I’m not here to make you love reading. I’m here to make you hate it less. And if you already love it, then I’m here to protect it with all of my might.” ♥

Pernille’s book, Passionate Readers, goes into a lot more detail than I have room for here. It really walks teachers through how to implement a more reader-centered approach to teaching reading, complete with all the possible obstacles and pitfalls. I really encourage you to get a copy. To read more from Pernille Ripp, visit her fantastic blog at pernillesripp.com.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Come on in!!

Oh, what a wonderful post and interview with Ripp! Thank you for sharing. I have slowly made my way from the limits of reading levels and have been more open to choice and giving students voice in what they want to do. This year, I am trying the 40 book challenge, and I love it. I love being able to tell a kid “a book is a book” when they come asking if a graphic novel counts. I feel so lucky to have a school that has moved forward as well in terms of reading, but we have so much farther to go. I look forward to more of your posts.

There is a creative way in which works in the classroom, to get students to read extracurricular books outside of the classroom. Just create a book club in which the students encourage each other to read more.

Penny Kittle’s book, Book Love, is a must-read for any high school English department looking to reignite their sustained silent reading and responding program.

Thank you for this article! I teach 3rd grade and have always believed in the power of reading. I have hundreds of books in my classroom and give time every day (first thing in the morning) to read the books of their choice (admittedly within a range of levels so a 2nd grade level reader is not reading a kindergarten or 6th grade level book). Often times it is the only reading time some of these students get. This article validated the actions I’m taking to try and teach children the love/power of reading. Seeing a child reach the point where they are successful at reading a book they never thought they could read is the most rewarding experience.

I am a 9th grade teacher at a “priority” school in Nashville, TN, and, in my 8th year of teaching, I have finally been able to consistently carve out time for independent reading in my classroom. It is amazing, and I have clung to it, then worried about it, then reaffirmed my stance every week of the semester. So… Thanks for the additional affirmation! I do have a question: I feel like I am failing at reading conversations with my kids. When it seems obvious that a student is lost, how do I get him/her to go back without killing their love of reading? How can I learn to support their comprehension before they are staring vacantly at page 85? What books should I read to learn more?

I would start with asking them how they are lost and trying to find out why they are lost. They are many reasons kids get lost and sometimes they are not even aware of it. So getting them to tune into their reading and also pushing kids to have great reading experiences helps a lot. My students start wanting better reading experiences and not wanting to be lost and so often that goes back to book shopping again with them. Remember, the point is for them to start independently monitoring their own reading lives, not just rely on us every step of the way. I discuss this more in Passionate Readers but Book Love by Penny Kittle is a must read as well.

Pernille, I am wondering if you have them read on their own beyond the 10 min per day in class — like, at night. In the past, I have done that — independent reading (w no packets) for homework — with some good results, I think. I am at a new school that generally has a no/low HW policy, which I like. I’m just wondering if 50 min per week is enough time to build that love of reading we are all looking for, esp since it takes most readers, including me, several min to ‘fall into’ the book, at which point in the 10 min window, we’d be pulling them back out. Or is your experience that this 10 min per day is enough to get kids reading on their own by choice?

Hi Steven,

Yes! Reading outside of class has always been a concurrent goal, albeit some students never quite reached out. I asked them to read 2 hours or more outside of class in a week and we checked in through their goal setting and conferencing. There were no logs or reading responses attached to it. When I moved to a longer block (90 glorious minutes) I upped their reading to 20 min a day at the beginning of class but kept the 2 hours the same. I think the 10 minutes is enough to plant a seed and to also study kids and their habits in order to support them further but they definitely need more time to further develop their reading and their relationship to reading..

I have been reading No More Fake Reading, which also addresses this topic but talks about modeling how to read with excerpts from classic literature and then giving kids time to practice those skills with their independent choice books.

I am a mother of a 2nd grader who takes time to process and has struggles with reading. I want to motivate her more to still have a love of reading inspite of challenges. The school assigns reading comprehension questions with passages every night and asks them to read. What can I do to encourage her to love reading more? She wants to read Decendents 2 books which are over her head . I would rather read the chapters with her rather than those passages – any thoughts . And she wants to start a book club

Read aloud at home, do everything that you can to foster the love and then have the passages be homework. here are more ideas of what parents can do to help at home https://pernillesripp.com/2016/05/23/parents-how-to-help-your-child-keep-reading-over-the-summer/

You have mentioned a whole bunch of great resources that are for primary or middle school level. Is there a source to support reading at the high school level? I have been looking for help with implementing a reading program that also acknowledges SAT, AP testing and other kinds of standardized testing and curriculum requirements that are unique to high school.

I would start by reading Penny Kittle’s Book Love; she faces the same pressures and has been a fantastic advocate for how to do this with all of the high school components. Also, Kelly Gallagher’s books are phenomenal too and he teaches high school as well.

I really liked the point about the value of noticing when you don’t want to keep reading and giving students (or yourself) the permission to abandon a book. You probably still have enough information to say if a friend might like it, so even an abandoned book still has a lot of value, in addition to seeing what choices go into developing your “reading identity.”

Also, sampling and abandoning texts is a lot of what those of us who are researchers do! You need to make sure you choose texts that help answer your research question.

When my son was six he loved to play baseball. We would go outside every day and throw, catch, run the bases, and learn the game. Someone suggested he join the peewee league in town. He was thrilled. After a few Saturdays on the team, he no longer wanted to throw the ball or play outside. I asked him why. “Grown ups ruin everything,” he said. He also said he didn’t want to stay for two hours every Saturday, and play on Wednesdays after school. He didn’t want to get yelled at for not “playing” right…and that was the end of baseball. When I was a kid I could not wait to get my library card…I felt it was a privilege, because my parents made it that way. We left with stacks of books in our arms, excited we got to choose.

I feel sorry for kids these days–no free time, endless tests, and now forced to keep a reading log…grown ups took away one of the last vestiges that kids had…their own magical space to read.

What do we do if we are required by our district to use a basal reading program. HELP!!! I teach first grade and it is so hard for me to copy of a set of worksheets to have my kids respond to reading in writing. I feel like a terrible teacher and I am in my 21st year of teaching!

I am so sorry to hear this, I think you “sneak in” other reading opportunities for the kids whenever you can so that it is just not the basal. I also would encourage you to start reading the research on reading instruction so that you can start conversations about the programs being implemented. A great place to start is with this one from Allington because it leads you to more research http://www.readingrockets.org/article/six-ts-effective-elementary-literacy-instruction

These are great reminders of what is essential in reading: time, ownership, and response (as Nancie Atwell named them). My students grow in their skills and see themselves as readers with specific tastes when we give reading and readers time, ownership, and response.

As a reader and lover of books my whole life, it is so strange to me that parents aren’t carving out time for reading at home. We always have, starting as early as 6 months…bedtime stories every night. Now he reads to us and he will often go grab a book if he’s bored because we’ve spent so much time showing him how fun books are. We check out 30 books at a time at the library and he LOVES new stories. Maybe we need to work on this with parents too!

It’s not so much reading, but how much students hate writing that’s an issue.

This is definitely an issue as well and something I work on with all of my own students. Just last week they came up with the reasons when writing is trash or magical and so much of it boils down to them feeling like they have no choice and no real purpose. It is definitely something I am focusing on with kids as well.

I teach in NZ and we have used these practices for many years. You need to read for pleasure as well as information. I think it is so important to give kids time to read what they like in order to make it worthwhile for them. There is a place for reading more formally but reading books they enjoy helps to create positive reading habits.

Children are to be encouraged to read for meaning and for pleasure. I have used this method over the years but not extensively as it was used in this discussion. A well managed mini classroom library in all the classes in our schools would enhance children’s interest in reading for pleasure and also for meaning.

This is a thought provoking commentary. Ripp’s experience is quite helpful. This being said, I love reading because I can read for information. Choice is a great idea, but sometimes we have to read or do things we may not be as excited about, so how does that fit into this scheme? I think reading is not just something the ELA teacher does and should be expected to do. I think we are always doing “something” with our reading. I do not think it is necessary to do worksheets and such, but we are always doing “something” with our reading. In my opinion and experience, having students read “texts” they would not normally read has opened up their world to new ways of knowing, doing, and expressions, especially in Math, Science, and Social Studies as well as culture and language. So how does this work then when choice seems to take precedence? Just curious.

We make room for both. My students have to have self-selected choice reading so that they can have pleasurable reading experiences and then we also do things with what we read whether fiction or nonfiction. That comes after our independent reading.

I am always struggling with teaching skills versus analyzing a book to death such that a student never wants to hear its title again! This year I think I have struck a balance but I have a vague sense of guilt because I’m not analyzing novels, stories and poems as much as my teammates. Still growing! I look forward to translating this great information above to what I can use at the 7/8th Grade level. I love Pernille’s work. Thanks for posting this.

You’re so welcome!

I love this yet am concerned that we are preaching to the choir here. We need to get the word out, we need to talk with our elected officials, we need to get INTO the schools as parent voices and volunteers.

A well written article, but a crucial piece is missing—a parent’s role in their child’s « love of reading ». My daughter’s teachers did exactly what they were (and are) expected to do. They taught her how to read! How to decode, use context clues, read for meaning, infer, make predictions etc… It was (and continues to be) MY role to foster my child’s love of reading. She sees this by watching me read, by having discussions with me about her reading and book choices, by discussing stories with her friends, and by making book purchases/exchanges a regular family outing. I always chuckle when I read articles that simply want to point fingers at schools and teachers rather than work with them! Come on parents—read with your kids!

Hey, Shelley! I couldn’t agree more — the role parents have in their children’s lives as readers is undeniable. Parents need to be reading to kids and with kids all the time; as a teacher, it pained me when I’d have parents of kids who wanted to stop reading with their kids once they could read independently. As a mom, I read every night with my kids, I think up until middle school. Great conversations. Great bonding time. I saw the article a bit differently; I didn’t see that it was pointing fingers at teachers. I really thought it was more about making sure that whatever teachers are asking kids to do in the classroom, is authentic. We want to make sure kids have some time in class to simply immerse themselves in a book without always having to “do something” with it. My goal as a teacher was for my kids to be able to transfer what they learned in the classroom to life out of the classroom — so if I wanted them to be readers, real readers when they walked out my door, I needed to make sure I gave them opportunities to practice that. With parent support.

I think some finger pointing is needed — when practices are harmful, that harm needs to be pointed out and the problems identified in order to do better. Of course the influence of parents is crucial to reading, but there are kids who don’t have that luxury and the teachers can’t control it, however, they can control the practices in their own classroom. And for a blog called “cult of pedagogy”, it makes sense that it addresses pedagogy and not parenthood.

This makes me cry! I have been teaching for 20 years and this year we have been forced to teach from a program that only allows for excerpts, passages and worksheets. IT IS AWFUL! Your article really hits home.

Why such a negative heading of the article?

It’s written so well…but to be honest very disappointing title…

Hi Mit. Well, I gave it this title for two reasons. One, I do believe our current practices ARE killing the love of reading, and that this is a serious problem, and that many teachers who are being forced to teach reading with passages and computer programs know deeply that these programs are killing the love of reading, so I wanted to speak to those frustrations. And two, I needed to title the piece in such a way that people would actually read it. If I had called it “How to Help Students Love Reading,” it would have been largely ignored. I’m addressing a problem here, not just celebrating something good, so I felt the title needed to reflect that.

With all of that said, I’m so glad you came over and read it anyway, and that you found value in it.

Great post. As a former early childhood educator who worked with parents in their home, we constantly pressed the importance and love for reading with kids, and I honestly think even the most high risk groups “got it.” Truly, I think kids enter school feeling great about books and reading, and yes, somewhere along the way it’s killed. Not a stretch to use that term, and I applaud you. I think even more alarmingly it’s happening with boys, in particular in regard to the skill of writing. Every single resource I read about these topics echoes the need for choice for kids, and it seems like such a no-brainer to me since it’s the magic thing that works in every area regarding kids. Sadly, that concept is getting whittled away in today’s educational climate. Hurray for you teachers fighting the good fight.

I’m pretty new teacher and currently I am working with children who have significant reading challenges and at times behavior too. In prior years, they have received programs that were Orton Gillingham inspired along with computer programs focused on phonics and decoding instruction but they are still at a basic reading level despite prior interventions. The children I work with are in the 4th grade and several should be in 5th. When I first started in August these students were pulled out for a 30 min reading intervention that used a computer program targeted at their level. The program was a huge turn off to me as teacher and I had to work my tail off to keep them logged in and engaged with the program – it felt so meaningless to me. I have started to sneak away from the computer program and give them engaging storybooks that are more at their level with a theme in mind. So for example, now I have them reading really beautiful picture books about kindness with the idea that we will read them to the younger kids at the school. I did give them a bunch to choose from and they are practicing to read fluently with a partner. My inspiration was to focus on giving them a purpose for their reading – I feel this was very important to me as a child when I was a struggling reader myself. My next plan is to have them choose a special book and have them practice reading this book with partner so we can take a trip to the Nursing home down the hill from school. I don’t know how long my principal will allow me to deviate from the computer program and I believe his new push is to figure out shorter (15 min) Orton Gillingham inspired sessions with these kids despite the fact that I’m not trained in this approach yet. His main question to me about the storybook approach is how are you going to measure progress. It comes down to that for him. If I can show progress I might be able to get away the computer program and meaningless reading passages. These students also participate in 4th grade general education instruction by the 4th grade teacher and it’s focused on worksheets, reading passages and finding voc words in their book, etc. The instruction is not very inspired in my opinion.) So my question is what about struggling readers (who often have behavioral challenges) and the approach you talk about? How does your approach work with students who have a disability impacting their progress, keeping them below grade level at reading?

Hi, Gina,

You bring up some interesting points! I taught 5th grade for many years, and then 1st grade for many more after that. When it comes to reading, first and foremost, we always want our readers to understand reading is all about making meaning. When talking about a struggling reader, we’re typically talking about a student who struggles with decoding, which will likely affect fluency and comprehension. I became familiar with the Orton-Gillingham approach to teaching phonics when I tutored a 10 year-old who’d been diagnosed with dyslexia. Although I wasn’t an expert by any means, I did find there were great benefits from using a very direct and systemic approach like this one. Phonics instruction is just a part of literacy instruction. When kids are actually reading, we want them to be reading books they can read with independence, books they are working on with guided instruction, and books they pick of choice. I’m wondering if you can start planting some seeds or start some conversations with a couple colleagues around this post and its resources. You’ve already got some changes in place which sound awesome! Get their thoughts about other ways you all could still implement direct phonics instruction without all the drill and kill of reading worksheets. Here are a couple of other resources to check out: Catching Readers Before They Fall K – 4 by Pat Johnson and Katie Keier (don’t let the K – 4 throw you off; it’s a great resource) and Teaching with Intention by Debbie Miller. Because your principal sounds open to trying new practices, while monitoring student progress, you may also want to check out the post Hate PD? Try Voluntary Piloting. I hope this helps in some way!

I do give my 10th and 11th graders independent reading time. But many of my students who read at a high level (post 12th grade) will choose books that are written at a 4th or 5th grade level. I think they just want to choose the easiest way to spend as little time as possible reading. Granted, most will usually be absorbed during independent reading time. But research does suggest that some challenge (syntax, vocabulary) is important. With that in mind, I can’t help but feel that I am doing them a favor to require them to read The Catcher in the Rye (for instance). And the truth is, we can’t do both.

One of the simplest ways for teaching kids the joy of reading is to read to them. Back in the ’60s when I was in grade school, our teachers always had “story time,” even in 6th grade, our teacher would read books aloud to us as a class. Combine that with encouraging personal reading and you have a winner.

Another issues is determining if there are reasons that are hindering a child from reading. New science is finding some kids have difficulty reading with words on a white background. Their brains respond better with a specific color background.

Yes! Kids of ALL ages not only LOVE being read to, but we need to remember that listening comprehension is critical to increasing reading comprehension – not to mention so much modeling naturally takes place during a read aloud. I’ve also found that reluctant readers tend to seek out books which have been read to them, reading them with greater confidence and engagement.

Personally, I think the comment of the books “staring at” the students plays a huge role in this issue. Growing up, there were always books at my house. My dad read a lot and I could pick any book in my house. Also, my mom let me choose my book at the bookstore. Fast-forward many years and I now teach English literature at a college. I live in a Spanish speaking country so my students don’t read much, (in Spanish or English). It is a struggle. A lot of them didn’t have opportunities as the ones I had in regards to reading, or they only read what they had to in school, never for enjoyment. This post has been very motivational. Thanks!

Excellent reading for teachers to reflect on.

I am concerned that students are leaving their school library and not reading the books they checked out. How do you address making the school library part of the students reading identity and school reading culture? I hate to see students just depend on the books in the classroom and never visit the library. With so many cuts to her school libraries and school librarians iacross the country, how can we support these programs and make sure students include the library is part of their reading identy and lives?

If you haven’t already, check out How a School Library Increased Student Use by 1000 Percent. There are some really great innovative ideas in this post that you might be able to put into place.

“I am not here to make you love reading; I am here to make you hate it less.” My takeaway from this podcast. Fostering a love of reading doesn’t need to be limited to language arts classrooms. Bryce Hedstrom (on his website) has great guidelines for world language teachers. I have been developing a classroom library for years but independent reading has played a marginal role (at best) in my curriculum. This podcast has strengthened my commitment to putting whole books and student voices more at the center of instruction. Thank you!

This article really hits home for me, I’m finishing my BA in English and plan to be teaching in a few years. It’s important to me that I can go above the basic curriculum and help students “hate reading a little less”. I understand that parent involvement is important, but so many adults don’t like to read either, so they are going to be less likely to encourage reading at home or to help their children find something that interests them. I love the idea of stacking the classroom library with books of all levels so we can meet the child wherever they are. I also want to be able to spend some time reading aloud from a book that we can enjoy as a class and not have to necessarily analyze.

Hey, Jen — thanks for sharing and bring up reading aloud, my favorite time of the day! If something had to give, this just wasn’t gonna be it. Because reading is thinking, and because all good readers choose their books with some kind of intention, I just encourage you to make that read aloud time intentional and instructional in some kind of way. Here’s an article that features one of my favorite writers, Lester Laminack, and his book, Unwrapping the Read Aloud: Making Every Read Aloud Intentional and Instructional. Have fun!

I am a huge fan of you, Pernille Ripp! It’s hard for teachers to embrace a new philosophy about what we’ve been doing. IMHO, one of the biggest roadblocks to reaching kids is what we experienced as students at the grade level we’re teaching. So many of us instinctively feel that the way it was done to us is the way we need to do it to our kids.

I read #passionateReaders this summer, and I was extremely fortunate to participate in Ripp’s Facebook book study of her book. (Side note: Twitter is such an awesome resource because authors are accessible!!!)

I took a leap that I don’t usually take. To be honest, I take leaps all the time. But my “thing” is writing, not reading.

I work at a high school and have students in grades 9 and 11. I redid my classroom library using bins and genre. I gave my student a challenge: 16 books/year for my college prep classes and 24 books/year for honors classes. We start almost every class with 10 minutes reading (20 minutes for my block-scheduled classes). I pretty much embraced Pernille Ripp’s suggestions.

In my district, in NJ, we started 9/6. I have multiple students who are on their 2nd book. I have one student who is on book 6! No logs, packets, or worksheets. No grade attached to this reading! Holy crap–Ripp is on to something!!!

I can go on and on–and it’s only been 3 weeks. I have students who prop open their Chromebooks and “sneak” reading behind the screen!

My advice to anyone who will listen. Read this post. Listen to the Podcast. Get Pernille Ripp’s book Passionate Readers. Do everything Ripp suggests! Because it will make such a difference in your kids’ lives.

Reading has always been the number one skill I impose on students!

It makes me smile to know that you and Pernille are friends! Dynamic duo!

I’m a science teacher, and I think a lot of the points here could be said about science, too. Many young children LOVE science. They love bugs, or making slime, or dinosaurs, or leaves, or rocks, you name it. I’ve met a five-year-old kid who could tell me more about dinosaurs than I learned as a biology major in college.

But a lot of older students hate science. And I think we too often make science a chore rather than something to enjoy. Rather than let kids’ curiosity drive them, we say “do this worksheet on this topic you don’t care about.”

The more I let my students choose their topic, the more they care about it. And I think that’s no accident.

I do think it’s hard when all the pressure is on us to prepare them for the ACT or whatever other tests they have, or to check off boxes in the school’s curriculum. But there are still ways to put choice and enjoyment back in!

Anyway, even though English isn’t my content, this post has still given me a lot to think about!

I taught a high school elective called Reading for Pleasure for ten years before I retired in 2013. All these resources you mentioned are important for any teacher who wants to truly inspire independent reading. We read together, wrote together, talked together. Now my former students tag me on social media on pics of THEIR children reading. So happy to see this article.

After reading the article, particularly the emphasis on having a rich and wide assortment of reading material, I am wondering what the author thinks about reading books on a device. Our school has a subscription to Epic, which essentially provides our students with a library of 100s of books. I have mixed feelings, but confess that I read many books on my device.

I am completely fine with reading books on devices as long as there are access to other choices as well, and it is a choice for the individual. I know many would dislike to read on devices and there are also issues surrounding eye strain and screen times effects on the brain. There is research coming out that shows that e-reading can lead to less stamina and not as in-depth concentration, however, for some it can definitely be a bonus. What I miss though when kids read on devices is that it is hard to have the physical connection to a story and all that entails.

If the device is a true e-reader and nothing else, there shouldn’t be an eye strain issue. Many though unfortunately read on devices such as tablets and cell phones and other ‘e-readers’ that are backlit. I love reading physical books, but I also read on my Kindle that is strictly an e-reader checking out e-books from the library and whatnot.

I do 100% understand where you’re coming from though.

Great article and I am happy to see it is still going strong and being shared by teachers years later! I am the librarian at an elementary school that recently started pushing accelerated reader. I am feeling increasingly discouraged as it starts to impact student book selection and removes true choice. And it is so sad that I can’t recommend amazing books to kids because they need to be reading something at “their level”. “Their level” is based on an arbitrary numeric value attached to a book depending on page count and big words. But more and more schools are going this route and it is hard to be a book-loving librarian or teacher and have to play along with these systems. 🙁

As a future teacher, I absolutely love the idea of having a classroom library for students. Years ago, I remember checking out books from my teacher’s library and it was a great way to engage me in reading. I think it is so important that students are also free to choose their own books that they read. Forcing students to read a book that they don’t enjoy will kill their love of reading! Thank you so much for this article!

Glad you enjoyed the article, Lucas!

Thank you so much for sharing how to get readers excited about reading. I have fallen prey to the pressure of getting students ready for testing, and my students spend more time than I would like on the computer reading passages and not reading authentic text. I want to get back to letting my students read for the sake of reading and then taking time to confer with my students about their books. I am so excited to try Donna Miller’s 40-book challenge this year. In addition, I can’t wait to read the book, Passionate Readers. Thank you for reminding me of the importance of developing a love of reading and writing in my students and that I need to provide time every day for my students to read self-selected books.

Hi Denise,

We agree that reading and discussing authentic texts is crucial to the development of a love of reading in young people. Sounds like you’re on a great track for the coming school year- all the best!

Oh my goodness, I’m so inspired. I struggled to get my fifth graders to read, and now I will be teaching third-grade. It is my goal to get them excited about reading by helping them find what book fits for them. I will definitely use the ideas that you shared like the 40 book challenge, choice, and independent time to read. I will also continue to build my book library.

Thank you so much for sharing this post and interview with Ripp!s

Jenn will be so glad to hear you enjoyed the post. Thanks for reading!