Listen to the interview with Marcus Luther:

Sponsored by EVERFI and Listenwise

At the end of the 2021-22 school year, I sat down to complete my annual reflection on both the successes of the year as well as the walls I encountered.

The “wall” I was most fixated upon?

Making students better writers.

It was not that I felt students had not grown as writers per se, but rather that I did not feel as if I had a strong relationship with students around their growth as writers. In other words, had I asked students how they were different as writers at the end of our course, I honestly would have no idea what they would have said.

Rereading this reflection in my planning for this past school year, then, I made a commitment to make a simple, important shift in our classroom: I was going to ask students about how they saw themselves as writers more often.

Much more often.

In this post, I want to lay out the system we built, the “Story of Your Year as a Writer,” to make this asking much more embedded into our writing process and how this practice was interwoven throughout the year — not just pigeonholed at the end.

And while in our ELA classroom this asking centered around writing, I’d make the case that this could apply to any type of student learning for middle and high school, as the goal with this system is to support and prioritize student reflection on their own growth as learners as a regular, meaningful part of the classroom experience.

Setting Up The Reflection Documents

One of my frustrations thinking back to previous years of teaching has been how so much of the learning felt very much fragmented. There would be four to six weeks between formal writing opportunities, and even if we managed to have a good individual reflection process on a performance task, much of it would fade away before the next opportunity.

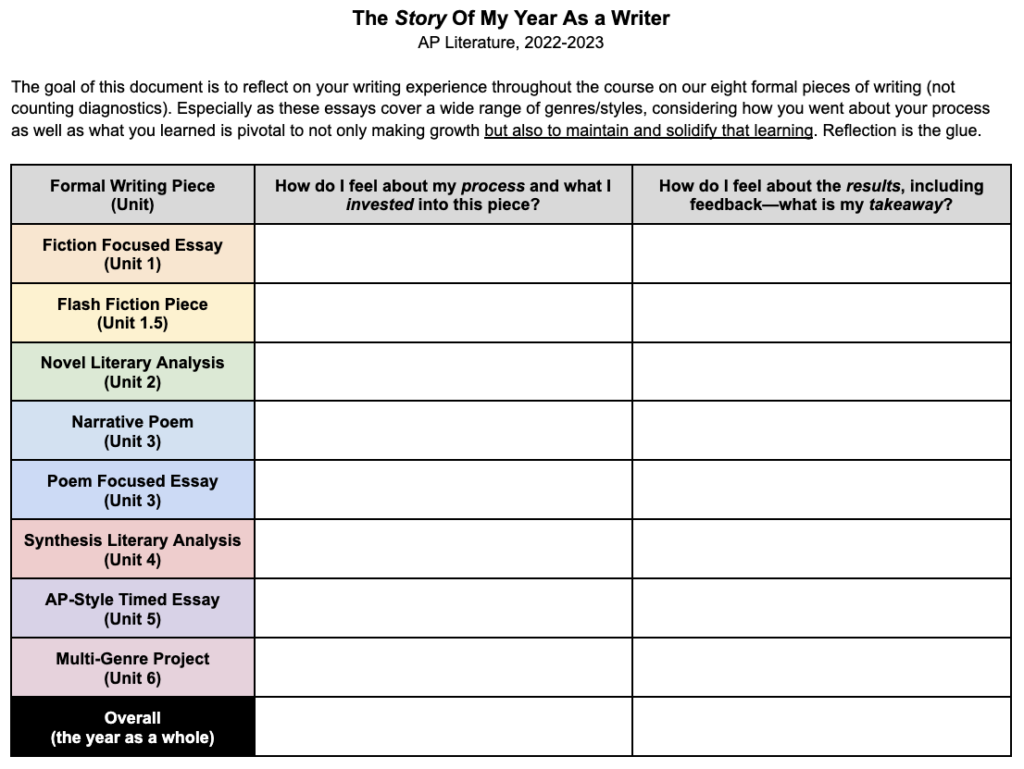

For me, this meant that it was a priority for all the reflections to live in a single place, so I created a template designed to do just that: a “Writing Story” document for each student (see image below). This is the foundation of this system of reflection, then, as students became quite used to walking into the room with the simple instructions projected on the board to “have your Writing Story document open by the bell.”

Though of course this document can look different for any given classroom — and could be more broadly called a “Learning Story” — the three priorities I’d recommend in getting it set up in your classroom are as follows:

- Provide reflection space for process as well as results. Too often reflection mixes these two together and there is something lost, I’d offer, in not handling them individually. The two category names for our document’s columns were as follows: a) How do I feel about my process and what I invested into this piece? and b) How do I feel about the results, including feedback — what is my takeaway?

- Include all the assessments on the same document. Thinking back on my own frustration around fragmentation, the purpose of this document is to have everything available in a single space, which allows students to observe and reflect upon not only individual learnings but also patterns and shifts. (Tip: You could do one of these documents for each semester if planning out the whole year’s worth of assessments in advance is too much.)

- Make sure you have access to the document. A driving purpose of this activity is to help students understand their own growth but also for you as a teacher to understand how students see their growth. This means you need access to the document from the get-go, which can be done a) by having each student share theirs with you and creating a “Writing Story” folder in your Google Drive or b) by you creating the document for each student and sharing it out to them individually. (Another tip: I found it helpful to also have editing access so I could add activities to complete on the documents themselves as the year progressed.)

On the set-up day for these documents, it also is a really important time for you to frame the purpose behind them for the class. In our room, this began with me admitting that I didn’t feel like I had the grasp I needed of each student’s writing growth the previous year, especially in their eyes, and also the practical goal of creating a “one-stop-shop” where all their key learnings and feedback could be accessed in a single space.

Does this take time on the front end? You betcha.

Is this time worth it? Yes, yes, yes, in my opinion.

Unequivocally, yes.

What “Reflection Days” Look Like

As much as I cared about setting up this new system of reflection well and navigating all the logistics smoothly, I knew the document itself would matter very little if it did not change the way I created space for reflection in our classroom.

So after our first formal writing opportunity, rather than diving forward into our next unit as I had in previous years, I planned out an entire “feedback lesson” in which reflection would be centered rather than tacked on last-minute.

This lesson — which you can see via the slide deck here from our first experience this past year — included the following activities:

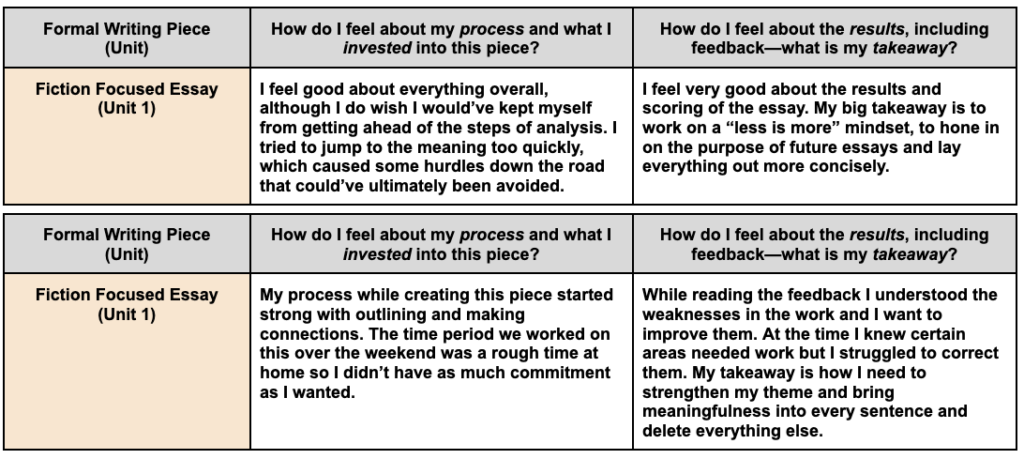

- Students reflecting on their process prior to getting their results and sharing those reflections with a small group

- Students getting a chance to walk through “feedback trends” as an entire class, anticipating which whole-class trend might apply to their individual writing and once again sharing their thinking in a small group

- Students spending individual time to read through and process their results and feedback, including their own reflections on their “Writing Story” document about what they took away from the feedback that was offered. (They also were asked to hyperlink their actual essay to the document so it would be one click away in case they wanted to review it at any point going forward.)

All in all, this was at least thirty minutes of class time built around reflection — and not just individual reflection, either, but also intentional conversation with peers about their writing process and learnings. The latter part of this lesson also created a great opportunity for me to circle around to answer individual questions they had about their results and feedback during the independent reflection time.

Ultimately, though, the important shift for me was creating this dedicated time for reflection in the classroom rather than just crossing my fingers and hoping it would happen individually outside of class. This also meant not releasing results to students individually while I was grading and giving feedback, as that would have prevented the whole-class experience around reflection. (For me, this means I create the Google Docs for students myself, rather than the other way around. I give students editing access so they can write their pieces, then remove sharing access while grading, though others may have different tools for this!)

I did want to offer two other brief notes about these days based on questions I’ve received from other teachers:

- What about students who did not complete the essay? Depending on the class, this might just be one or two students (who may have had extenuating circumstances) or it could be larger cohort — in which case I shift seats so that they aren’t in a group with anyone else who finished — and they get this period for a) work time to hopefully get this completed as soon as possible and/or b) a chance to conference with me about questions they still might have.

- What about students who are absent? The nice thing about everything being organized digitally is that it technically can all be completed independently — they can reflect on their process, look through the “feedback trends” (see previously-linked slide deck), and then read through their results and update their Writing Story documents on their own. However, I make it a point to check in with them about this once they’re back, as I don’t want them to fall behind on our year-long path of reflection.

How The System Evolves Over The Year

As all teachers know, it is one thing for any system in the classroom to get off to a strong start; it’s another thing entirely for that system to not only sustain but evolve meaningfully.

One of the best surprises of this past year was how our Writing Story reflection document did just this: evolving into an increasingly important part of our classroom community.

The first, most-logical evolution? How individual reflections became enriched by comparing them to past reflections. For example, after the third writing opportunity of the year, students were asked to reflect on their “process” over the first three experiences and to share the patterns they saw along with any shifts. In this way, the reflection was no longer fragmented — and students were talking with each other about how they were changing as writers not just as far as results but also the process that led to them.

Another nice surprise that I hadn’t initially foreseen? How impactful these documents were during in-person family conferences.

In our fall conferences with families this past year, it was an incredible experience to be able to immediately pull up the Writing Story document and have the student read their own words about their growth to their families. Of course, student-led family conferences are an important, increasing priority for many educators, but in this case I think what made them so successful was the substantive, system-aligned way that a foundation was built for them.

Students were not just sharing a last-minute reflection the week before conferences — they were walking their families through their own “story” as a writer over the year thus far.

How cool is that?

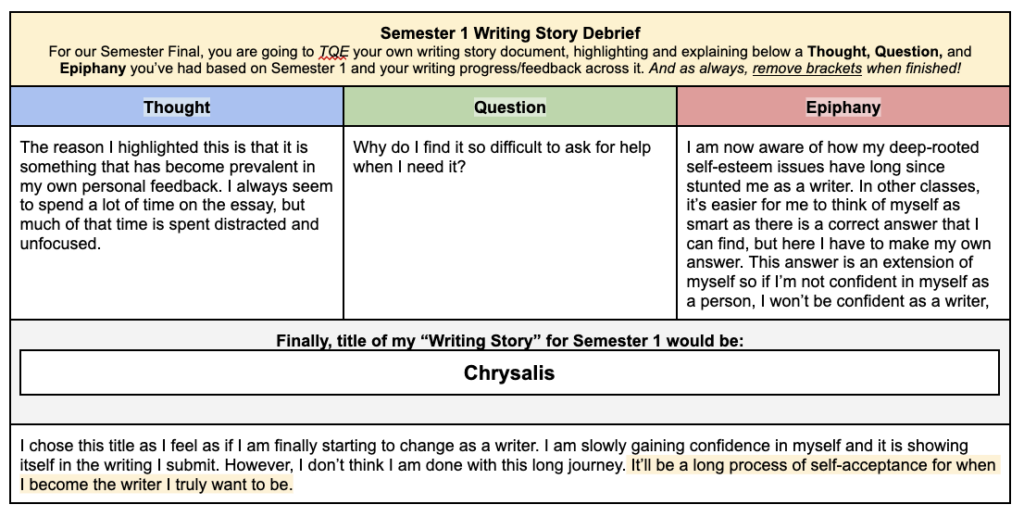

Speaking of cool (and yes, I’m quite enthusiastic about this system, as you can likely tell at this point!), I want to also brag on what students did at the end of the first semester. With a major assist from Marisa Thompson’s TQE system that is now core to our classroom, students spent the final lesson of the semester going back through and annotating their own reflections, identifying a Thought, Question, and Epiphany they had about their own journey as a writer at that point in the year. Then after sharing these out in a small group, they were asked to also come up with a title of their Writing Story so far — which they then went around the room full-circle and shared with an explanation.

To repeat: Our semester ended with every student sharing aloud whole-class, “This is the title of my journey as a writer and here’s why.”

To repeat: How cool is that?

One additional note: the document was really helpful in communicating with families outside of conferences about their student’s progress and effort — including one instance when a family insisted that a student had invested all weekend on an essay and was disappointed with the results, when on their Writing Story document the student admitted to rushing to get it done last-minute. Easy clarification on my end to pass on to the family that was only possible because of this system.

Closing The Year With Reflection Meaningfully

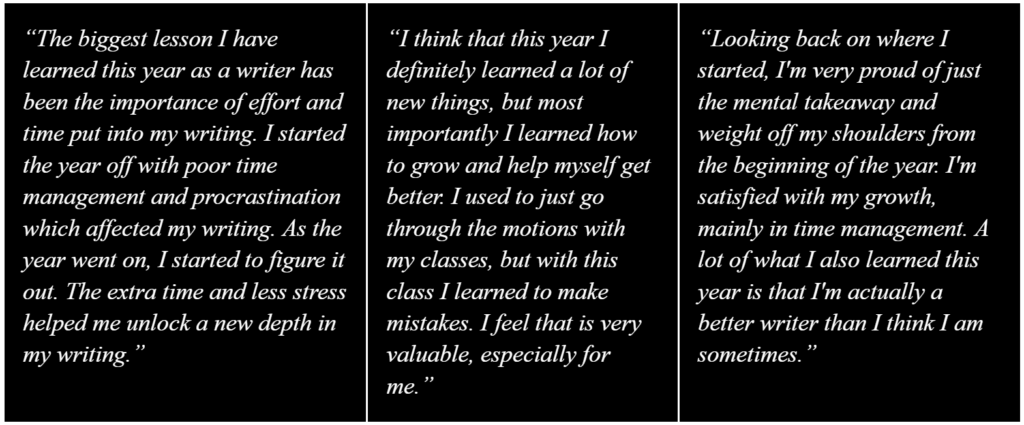

By the time we got to the end of the year, then, these originally-quite-blank documents were, well, quite full — as you can see from three different students here. (Note: hyperlinked student essays were removed from samples.)

We continued much of what was established in the first semester into the second, too, with students reflecting on patterns and shifts across the document, bringing them into conversations with families at spring conferences, and then completing culminating reflections that were then shared with small groups.

This interwoven system of reflection was also key, too, as we shifted towards centering student feedback on my own choices as a teacher in our classroom. I regularly try to create spaces for conversation with students about how they feel about what I’m doing, and the quality of their feedback is directly tied, I believe, to the quality of their own reflection — including on these Writing Story documents.

For me, nevertheless, the most important thing was that I now had a confident answer to the “wall” from the previous school year: I had a much better understanding not only of how students had grown as writers but also how students felt about their own growth as writers.

Collectively and individually.

Reading through some of their closing reflections on the document, I came across sentences such as these:

- “As a writer, I learned to trust myself.”

- “I have learned I don’t do things fast and I prefer freedom in my work.”

- “My biggest takeaway is that I deserve to celebrate my work.”

- “The most important thing I learned about myself as a writer was to give myself time.”

- “I’m more confident as a writer now.”

I’m more confident as a writer now.

What a thing it is as a teacher to read those words.

Of course, reflection is not the entire story. Students did a considerable amount of work throughout the year to achieve the growth they did, and I don’t want to pretend in this post that a better system of reflection by itself fixes all other issues in a classroom space.

However, the takeaway I’d offer is this: Never in my career have I felt this confident in my own understanding of the journey students made in our classroom as learners, and more precisely as writers — and never before have students spent more time in a given year talking about their own journey not just with me as a teacher, but collaboratively with our classroom community.

I know on my end as a teacher, too, that creating this system of reflection held me accountable to the value of reflection, even as so many other competing priorities found their way into the room, as they always do. This system made me better at giving individual feedback as a teacher and also helped me reflect more meaningfully on the patterns I was seeing across the classroom.

I believe reflection is a value we all hold as educators and one that we see as important for our classroom communities in every context. Yet I also believe that reflection is one of the easiest elements of any classroom to get rushed through, consolidated, or even shoved aside over the school year — and establishing a system to immerse it within the classroom is the best way we can all hold ourselves accountable to making it an ongoing priority.

I’m more confident as a writer now.

What reflection do you think you could read from your students at the end of the year?

It begins by giving them a space to do just that: reflect.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

I’m still listening to the interview and it inspired me!

Idea: create a template doc and copies for all but here’s the kicker!

In the header you link rubrics and instructions for all reflections so they always see it at the top of every page!

For example:

Link to rubrics

1. New reflections, always write at the top of the document, not the end

2. Title each reflection in this format “Unit 2”

I will be using this in my theatre class, perhaps in choir and typing. Have to think on it more.

Thanks for sharing this idea, Rachel! Jenn will be so glad to hear that the interview inspired you to make a shift in your practice!

Thank you for this podcast! Highly recommend checking out LEARNING STORIES: CONSTRUCTING LEARNER IDENTITIES IN EARLY EDUCATION by Carr and Lee for some amazing research and ideas in doing reflection with our youngest learners. I read the book over the Summer and am experimenting with how to build in time for learning reflection in my new TK classroom.

Thanks for sharing this, Allia!

I started doing these in my classroom this year after every assessment, and I really like how it shifts the focus of the assessments from the grades to the feedback. And the presentations I do on reflection day give me and the students great insight on what went well and what was challenging for us. Thank you!

Thanks for sharing this, Andrea! I’m glad this has been such a beneficial practice for you and your students.