Listen to the interview with Kareem Farah:

Sponsored by Hapara and Kiddom

Most teachers can relate to that sinking feeling you get when you forge ahead to a new lesson even though many of your students aren’t “getting it.” The pacing guide says it’s time to move forward, there is a planned assessment just a week away, and you feel compelled to keep pushing through. But you know that isn’t what’s best for kids. Skills build on each other. Kids can’t sprint before they walk. They can’t write a paragraph before they write a sentence.

Ultimately, every educator wants to create a classroom that honors the fact that students must first master foundational skills to access more complex content. But we don’t provide them with a blueprint for how to do it. We expect mastery from students, but don’t create the conditions that give them the time and support to achieve it.

The good news is, the final frontier of the blended, self-paced, mastery-based model we have created at the Modern Classrooms Project addresses this very challenge. In this piece, I’ll lay out the structures and systems you need to cultivate a mastery-based classroom of your own. With the growing diversity of academic and social-emotional needs as a consequence of the COVID pandemic, a mastery-based approach is not just valuable, it is necessary.

The Value of Mastery-Based Grading

Before you make the leap into transforming your classroom around mastery-based grading, it’s critical to understand why it is so valuable. At its core, mastery-based learning refers to the notion that students must meet a certain level of competence for a task or skill before moving on to the next. Aside from it sounding quite sensible, there are some core reasons why mastery-based grading is truly valuable for students:

- Prevents lingering skill gaps: Every teacher knows what it is like to start a lesson, only to realize a few minutes in that a number of students aren’t ready for it. This is the consequence of sustained skill gaps. Kids have been pushed through class after class and lesson after lesson without achieving actual mastery. We collectively sweep foundational skill gaps under the rug, knowing that eventually it is going to create challenges for students when presented with more complex skills. It also leads to enormous variability in learning levels within the same classroom, school, or district. It is no surprise that when mastery-based grading is implemented effectively it is associated with a decrease in the amount of variability in aptitude between students (Anderson, 1994; Kulik, Kulik, & Bangert-Drowns, 1990). Moreover, it leads to a substantial increase in students’ ability to retain their learning long-term, thus ensuring they are set up for success when they leave your classroom (Kulik, Kulik, & Bangert-Drowns, 1990).

- Builds student confidence: Mastery-based grading is integral to building students’ sense of self-worth in the classroom. Kids are not oblivious to the fact that they are being moved on from one lesson to the next without actually fully grasping the skill. In fact, every time they do get pushed forward without achieving mastery, they question whether or not they are holistically “good” at a particular subject. When this happens over and over, they question whether they are even capable of academic success. In a mastery-based setting, where students are given a true opportunity to succeed, they develop more positive attitudes toward the content being taught. (Anderson, 1994; Kulik, Kulik, & Bangert-Drowns, 1990). More importantly, they start to believe in themselves as young scholars and ultimately improve their academic self-concept (Anderson, 1994; Guskey & Pigot, 1988).

- Prepares students for the real world: In my first few years as a classroom teacher, I thought the best way to support my students was to just give them everything they needed. I shielded them from productive struggle, I didn’t require mastery, and I conditioned them to believe completion and effort were sufficient. At the time, I thought I was doing what was best for kids, only to realize later I had let them down. I misrepresented how they would be treated when they left my classroom and traveled on to college or the workplace. In these settings, they felt blindsided when suddenly they were held to mastery. They needed to show competence and were expected to be self-aware enough to identify when they needed to engage in further learning or seek out additional support. When we don’t hold our students accountable to mastery, we fail to prepare them for what’s next in life. We sell them a false reality that will only hurt them in the long run and sometimes when it is too late.

Setting the Conditions Needed for Mastery-Based Grading

It can be hard to imagine how to implement mastery-based grading when you have never done it before. The core limitation is the attachment most educators have to fixed-pace learning. To implement mastery-based grading you have to challenge the status quo of traditional systems where all students have the same amount of time to achieve competence. Instead, in mastery-based learning each student continues to spend time on a skill until they achieve proficiency (Dick & Reiser, 1989).

For that to become a reality, educators need to infuse elements of self-pacing in their classroom so they can let some students work on one lesson while others move on to the next because they have achieved mastery. Instead of looking at a unit and saying students NEED to learn lesson #1 on Monday and lesson #2 on Tuesday, we need to honor the fact that learning just isn’t that rigid.

Now I could write a whole piece discussing how to build a self-paced classroom, and the good news is I have! To learn how, explore our free online course* or read my previous piece here on How to Create a Self-Paced Classroom.

The Two Stages of a Student’s Journey Towards Mastery

Once you have established the conditions necessary to grade students on mastery, then it’s time to design the systems necessary to make it happen. Reaching mastery is a journey and typically involves two stages:

Stage 1: Developing Mastery Through Practice

As soon as a student is exposed to a new skill, they need to practice that skill. The practice stage should be where they spend the majority of their class time. It is when students are truly developing their understanding of the material. Designing effective opportunities for practice should include:

- Application of the Material: For practice to be productive, it must include applied learning. This can be done through discussions, labs, readings, worksheets, and other activities. Some of the best forms of practice are driven by inquiry and constant questioning. The experience should be scaffolded so students are systematically engaging in more challenging work as the lesson builds, bringing the student closer and closer to mastery.

- Opportunities for Collaboration: Ideally, practice time is collaborative. Students should be able work together to understand new content and ask questions to peers who may have already mastered the skill. In an effective mastery-based environment, educators are also working to build students’ ability to be self-regulated learners. Instead of running a teacher-centered classroom, students should be at the center and teachers should serve as a guide as students lean on each other through the journey to mastery.

- Constant Revision: One of the most important elements of building an effective mastery-based grading classroom is cultivating a culture of revision. Students need to internalize that to achieve mastery you should EXPECT to revise your work. This is a novel concept to many students and will result in some pushback, which is a good thing. During this practice time, students should be submitting assignments and receiving feedback from their teacher on areas that need improvement. Unlike a traditional setting, where students turn in assignments and never see them again until they are “graded,” in a mastery-based classroom, students are constantly revisiting their assignment until they understand the material enough to demonstrate their mastery. To revise effectively, students should receive clear feedback on what they do and do not yet understand. They should also receive actionable suggestions for what they should do to progress to the next phase of the learning process where they will demonstrate mastery.

Stage 2: Demonstrating Mastery Through Mastery Checks

Once a student has practiced sufficiently, it’s time for them to demonstrate that they truly are a master of the skill! To provide students with this opportunity, educators need to design effective assessments that allow students to prove their understanding of a given skill or concept.

We call these assessments “mastery checks,” and students take them at the end of each lesson prior to moving on to the next one. They emulate the function of an exit ticket but aren’t administered at the end of a class period. Instead, mastery checks are administered when a student has practiced the content adequately and feels ready to show their understanding of the content in a controlled setting. Designing effective mastery checks is integral to running a mastery-based classroom. Here are some important characteristics to consider:

- Administered Individually: Unlike the collaborative practice stage, students take mastery checks independently. It is students’ opportunity to show that they can execute the skill without the support of their peers. Mastery checks are taken whenever students are ready for them, so you will often have a number of students demonstrating their mastery on different lessons at the same time. To manage the workflow and reduce the chances of cheating, many educators create a “Mastery Check Zone” in their classroom. That area of the classroom is completely silent and reserved for students who are demonstrating mastery.

- Easily Assessed: At this point, you can probably tell that a mastery-based learning environment requires a fair amount of grading. The key is the grading is purposeful and leads to real data-driven instruction. To help manage the flow of work, it is important to build mastery checks that are easy to assess. These are ideally bite-sized and do a nice job of balancing depth of understanding with efficient assessment. We encourage educators to use a mastery check template to keep a consistent structure. Keep in mind that mastery checks do not all need to be the same format or be delivered in the same medium. They can look like a mini-quiz, a sorting activity, or verbal assessments. As a teacher, you will know best what a student needs to do to demonstrate their understanding of a skill.

- Opportunity for Reassessment: The heartbeat of an effective mastery-based grading environment is reassessments. Students and teachers should all come to the collective understanding that part of the journey to mastery is frequently falling short on assessments, reflecting on why, and then re-demonstrating mastery. To do this effectively, teachers develop a clear understanding of what constitutes mastery and then hold students to it. To support this process, a number of educators build rubrics for their mastery checks to ensure the grading process is as efficient as possible and the evidence is clear when a student needs to be reassessed.

Many educators build multiple forms of each mastery-check to allow for easy reassessment. This is highly contingent on the content area. For example, in math classes where students are learning about factors, it is quite straightforward to build multiple forms of the same mastery check. Alternatively, in an English class where students are learning about character and theme, it may make more sense to simply have students revisit the same mastery check if they did not achieve mastery.

Bear in mind that there is no one universally accepted method to executing a mastery-based grading system. You are the expert in the room and understand best what will work for you and your students. Once you have a plan, make sure to articulate it clearly to your students. Nothing should feel like a surprise.

Preparing for Pushback and Challenges

As with any important and innovative shift you make in the classroom, you should expect pushback and setbacks. Traditional practices in teaching and learning have remained in place because they are comfortable and often convenient. Don’t be surprised if students, parents, colleagues, and admin express hesitation about your vision. More importantly, expect to have your own doubts throughout the process. Prepare yourself for these common transition challenges:

1. Student Frustration

Most students have spent their educational career in environments that did not expect mastery; they are used to moving on to the next lesson regardless of competency. So when they enter a mastery-based environment, they will inevitably be surprised and quite frustrated. The first time they are asked to revise or be reassessed, they might ask why and in some cases express anger that you aren’t simply just moving them on. This type of reaction is all the more reason we need to move forward with mastery-based grading. This is good pushback, an indication we are truly changing students’ perception of learning in a way that has long-term positive impacts. The key is not to be surprised by it and to be prepared to articulate the rationale for the shift. The more frustrated your students get, the more they likely need to learn this shift before it is too late.

2. Working with Traditional Gradebooks

Often at the Modern Classrooms Project we field questions regarding whether a mastery-based grading approach can work with a traditional gradebook. I can assure you the thousands of educators who have implemented our blended, self-paced, mastery-based approach do so in traditional schools and districts that require A-F grades quarterly. The shift you are making is largely centered around how you actually treat grading each individual assignment and mastery check.

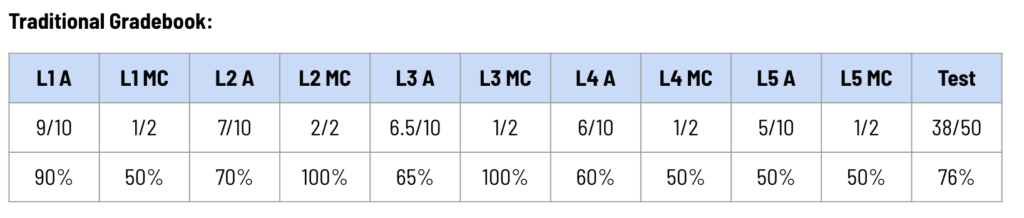

Take the example of a unit with 5 lessons and a summative assessment. Let’s assume each lesson has an associated assignment (scored out of 10 points) and mastery check (2 points) and the summative assessment is a test (50 points). In a traditional fixed-paced classroom where students aren’t graded based on mastery, a student might get the following grades:

The problem with a structure like this is students and teachers alike don’t actually know what lessons have been mastered. The partial credit grades tell us very little about a student’s competence of skills. It ultimately leads to a letter grade that is hard to explain.

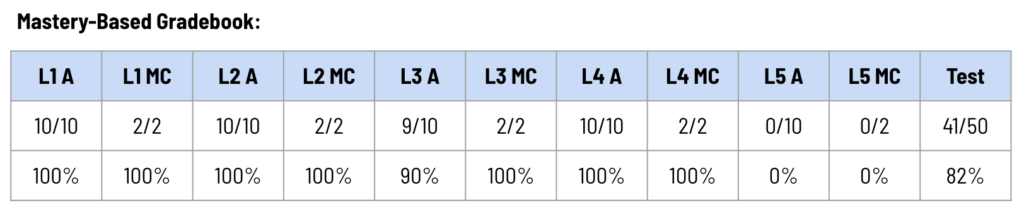

Alternatively, in a mastery-based grading system, you can use the exact same grading structure, but simply only award students with credit if they have achieved mastery. Therefore, a student might get the following grades:

The beauty of this approach is both students and teachers know exactly what skills kids do and do not understand. In this example, the student mastered Lessons #1-4 but not #5. Naturally it will also be reflected in the summative assessment where the student scored an 82%, which is expected given they mastered 80% of the lesson.

One thing to note is that most educators we support through our model only self-pace within each unit of study and still give summative assessments at a scheduled time. They usually grade those “traditionally” and use them as an opportunity to reflect with their students and craft a plan for addressing students’ gaps in understanding.

3. Keeping Up with Grading

As an educator who spent my first 3 years in the classroom teaching traditionally, I HATED grading. It was certainly mundane, but worse, it didn’t feel purposeful. I wasn’t using the information to drive my instruction. By the time I passed back work, my students had already forgotten about what they did. It felt like busy work that took up way too much time.

In a mastery-based grading environment, there is a fair amount of grading. Teachers often express that keeping up can be challenging. But the grading actually matters. It drives the discussions you have with students in small groups and individually. It triggers revisions and reassessments where students use your feedback to revisit skills to build competence. There isn’t a silver bullet to reduce the grading load. Some teachers leverage tech-based assessment to accelerate the grading. Others spot check assignments and focus their energy on mastery checks for efficiency. Ultimately, you will strike the right balance, and will derive relief and excitement from the fact that grading actually feels purposeful! (Listen to our podcast on managing grading here.)

Where to go to learn more

Creating a classroom built around mastery-based grading is challenging! It requires thoughtful planning, detailed grading and a commitment to doing what’s best for kids even when there is pushback. I can assure you the benefits outweigh the challenges. Both I and the teachers we have trained at the Modern Classrooms Project can attest that the transformation to a mastery-based grading approach has lasting impacts on students’ perceptions of learning and their sense of self-worth. For students to believe in themselves, they need to be given the time and space to truly demonstrate their excellence.

If you’re interested in launching a mastery-based classroom of your own, a great place to start is our free online course. The course provides an in-depth overview of our blended, self-paced, mastery-based instructional model packed with templates, tutorials, exemplar units and other useful resources. Additionally, you can hear from real Modern Classroom teachers and mentors as they share about their experience by listening to our Modern Classrooms Project Podcast.

Finally, if you’d like more structured support as you make the leap into mastery-based grading, consider enrolling in our Modern Classroom Mentorship Program. As part of the program, you’ll be paired with a mentor and receive 1-on-1 coaching, feedback on instructional materials and plans you create, and ongoing support from the broader Modern Classrooms community. Most importantly, you’ll leave the program ready to launch a mastery-based learning environment of your own.

Regardless of your next step in your professional learning journey, challenge yourself and the many assumptions we have made about grading practices in education that don’t contribute to learner understanding. More importantly, work to hold your students to mastery because they deserve nothing less. When we hold students to high expectations, they rise to the occasion.

References

Anderson, S.A. (1994). Synthesis of research on mastery learning. Information Analyses (ERIC Reproduction ED 382 567).

Dick, W., & Reiser, R.A. (1989). Planning effective instruction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Guskey, T., & Pigott, T. (1988). Research on group-based mastery learning programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Research, 81(4), 197-216.

Kulik, C., Kulik, J., & Bangert-Drowns, R. (1990). Effectiveness of mastery learning programs: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 60(2), 265-299.

* Cult of Pedagogy has an affiliate relationship with the Modern Classrooms Project. Although the Modern Classroom Essentials course is free, if you purchase one of their paid offerings through the links on this post, Cult of Pedagogy will receive a percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

When discussing mastery grading, you often refer back to proficiency. In my experience, mastery is rarely if ever attained by a student. To reach mastery infers that there is nothing left to learn; that you are now an expert. I suppose this is true if you define mastery that way. But to me mastery is a lifelong journey. proficiency on the other hand suggest that you have learned the skills and can in fact apply those skills in various situations. So, most of us should be content at the attainment of proficiency, the ability to move forward with a level of comfort in the concept in skills.

Danny, you make a very valid point about the distinction between proficiency and mastery. In our model, we believe deeply in teacher customization. So an educator may consider mastery of a lesson as achieving 4/5 on a rubric. That doesn’t necessarily mean they have learned everything possible on the skill, just means they have meet the level of mastery outlined by the educator.

It is not uncommon for educators to use “proficiency” or “competency” instead. Thanks for your thoughts!

Kareem,

After listening to your podcasts with Jenn and reading the accompanying blog posts, I have started the Modern Classrooms free course. For the last three years, I have been using design thinking as the problem-solving methodology my students use to create solutions for genuine challenges faced by non-profit organizations in marginalized communities across our city. This approach is grounded in both learner-centered and problem-centered curriculum designs, and I see a great deal of synergy between it and the Modern Classrooms approach. Given your expertise, I’m hoping to get your feedback on the soundness of my rationale.

To provide a little context, the Leadership course I teach is for Grade 11 students and in an effort to provide them with experiential learning opportunities, I have partnered with a number of local, non-profit organizations who are experiencing various challenges. The students work in collaborative groups and are positioned as consultants and use design thinking to develop their solutions to these challenges. The framework of the course is a blend of learner-centered and problem-centered curriculum designs and this is where I see a great deal of similarity with the Modern Classrooms project. I would like to incorporate your approach into my current pedagogy, and before I get too far down the road, I want to make sure I have an understanding of your design.

Using the Understanding by Design framework to work through the planning, assessment, and instruction for the course, I think there are a number of points of intersection in our programs. The planning is designed around the needs and interests of learners with lesson plans based on creating learning experiences for students. The kids are encouraged to actively construct their own understanding of the course content. This seems to align well with your application of the material phase as it is self-paced and iterative. I also think the learner-centered approach is depicted through the role of teachers as awareness makers and facilitators in classrooms that are collaborative, social environments. Furthermore, your assessment seems to fit this design as it uses self-assessment and peer assessment to develop concept mastery through the use of formative and summative assessments as well as mastery checks (this is a component I would like to add to my class). If I understand the Modern Classrooms practice correctly, I also believe that assessment guides curriculum and instruction. The challenge I see here is that the teacher has already created the video lessons. While this aids with predictability, does it also promote rigidity in content delivery? Other than students examining the coursework in a self-paced manner, how does the teacher account for different learning styles?

As mentioned, my course also uses a problem-centered design and as such relies heavily on using contemporary social problems and positions the teacher as a facilitator or guide to help students by providing instruction based on the problem and social context. The ideas are studied in depth within a unit and then transferred to subsequent units, and I am curious how the flipped classroom approach can be transferred to this design. I try to avoid whole class lectures so I really see the value in your hybrid model, focusing more on individual discussions with each student group. I think the self-paced component works well as I use the design thinking cycle (immersion, ideation, and implementation) to delineate three distinct units and within each there are formative and summative assessments. I already use a blind, iterative assessment practice in which students receive feedback on their rubrics, but no marks. This encourages deeper engagement in their learning as they have to actually read the feedback and determine what needs to be revised. They can resubmit their work when they feel they have mastered (I will now be using this terminology) the activity, but it has to be completed by the end of that unit. Do you view this assessment practice as being in the spirit of self-paced learning? I use it to guide curriculum iterations and instruction and I use the “practice, practice, practice, graded assignment” framework you talk about on the podcast.

I am also looking to build out a Grade 12 course that is an open-source, interdisciplinary class in the model of Don Wettrick’s Innovation and Open Source Learning class. Have you used the Modern Classroom Project’s approach in this manner? From what I have read, it seems it is being incorporated into subject-centered curriculum designs that focus on comprehending and conceptualizing content. I understand that this approach is more manageable, but is it is not also counterintuitive given that it doesn’t allow for individualization and deemphasizes the learner?

I look forward to your insights and suggestions.

Everything you have described is certainly in line with our model. We believe deeply in teacher customization. Every lesson doesn’t require a video. Every unit doesn’t need to be linear. Every assessment can be evaluated and delivered in different ways. As long as students aren’t listening to live lectures, are given the flexibility to spend more or less time on a given skill than their peers and you are providing feedback through the lens of mastery then you are making it happen.

Thanks for this article, Kareem.

How does the Modern Classrooms project determine the order of skills it assigns for students to progress through?

Do you find any challenges in assigning a linear path for students to achieve and demonstrate mastery? This has been one of our stumbling blocks in the past.

Hi Adam,

The Modern Classrooms Project doesn’t make that determination, the educator does. Plenty of educators we support use non linear approaches to implementing our model. Instead of requiring students to master one lesson before the next, the teachers requires students to master a set of skills (in any order) within a given timeframe. Hope this helps.

Best,

Kareem

Good morning,

I read this post and chewed on it overnight. I noticed a few issues of concern that perhaps merit consideration. After all, when making systematic changes in complex systems it is common that a new problem, greater in negative outcomes than the original problem, is inadvertently created. We have a LONG history of such outcomes in education!

The article pointed out powerful contributing factors that hamper optimal student performance. The author cites, but doesn’t name, social promotion as a key problem. The author then suggests that changing the grading structure will correct social promotion. I think this should be considered carefully. Is our current grading system what causes social promotion to occur? If the answer is no, then how does changing a grading system address the root causes of social promotion? If it fails to, then social promotion will still exist. The positive end of the trade off on this account might not exist at all.

The second issue is the claim that we teach to mastery. That’s what we say we do, but it is entirely untrue. We teach to a level of proficiency, not mastery. Mastery, even academic, requires years of practice and review. Our goal has never been to develop mastery. This is not merely a semantic argument. I’ll not get into that right now. However, it is fair to say that if we don’t carefully articulate our direction and goal, then we cannot succeed. We have never aimed at mastery, so to cite failures of achieving mastery as the impetus for change is ill-founded. Again, as with social promotion, the author correctly describes a problem but then promotes solutions that likely fail to address the issue cited.

The author further claims that resistance to this new protocol is rooted in two things, comfort and convenience. To me this is a dirty statement rooted in arrogance. It is the voice of a bad actor. It categorizes those that might question or push back as being stodgy and lazy. This does not foster the type of civil disagreement that needs to occur when considering large changes. Further, teachers are very ready for meaningful changes in education. What veteran teachers are tired of is the rebranding of stale ideas that don’t work.

Solutions that don’t address the root source of problems are bound to fail. Maybe I misunderstand his direction and perspective. I’d be glad to hear other views and reconsider my own.

Philip, everyone is entitled to their opinions. I personally think Kareem and the Modern Classrooms Project are really on to something, and I chose to feature his ideas on my site three different times this year as a result. All educators have been having conversations about what’s wrong with education for years and years, but very few schools make any big changes. If the method presented here has flaws or you take issue with the way Kareem is describing it, that’s your prerogative, but calling someone arrogant or characterizing their ideas as “stale” is counterproductive. I featured a similar method years ago from another teacher, so clearly I’m a big believer in the self-paced method, as are many of the teachers who have since adopted this same approach in their own classrooms. But what I try to do on my site is share ideas that are working, not push them out as the end-all-be-all. If it’s not for you, then feel free to share what IS working.

Philip,

I just had the conversation with my mom tonight who just had her last day of school in a 40 year career in education. We conversed about the rookie-veteran divide in schools. She, as a veteran, has talked about programs coming, going, and rebranding. She gets frustrated about new teachers coming in and seeing veteran ideas as outdated. However, just like a good parent does for their child, we should strive to do even better for the next generation. These techniques provided are so modern and not possibly a rebrand. This type of learning has only been made possible within the last decade! 1-1 students devices, powerful wifi, and the research to accompany is all brand new. It is not a stale, rebranded idea!

Regarding the comfort and convenience, in my classroom, I can think of numerous times I resort to comfort and convenience. My education and teacher training reflects ideas that served at one time, but now need change…but they are comfortable! I also have 30 minutes of prep, a class size of 28, IEP meetings, more social/emotional problems than ever before, 6 preps plus small groups, and a huge range of student ability. I am forced to choose convenience. When I heard that comment, I did not choose to feel offended, but rather I identified with the necessity to choose comfort and convenience. I encourage you to listen to Jennifer’s most recent podcast 170: No More Easy Button. She gets it! Often, we have no choice but to choose convenience. Unless we interrupt what isn’t working.

I am so grateful to have this tangible method to try a truly innovative new class format that can best serve today’s learners. The best part is that Kareem provides the research and data along the way, so I can trust in the process.

No we do not teach to mastery even though we say we do, but we should. It is so important especially in the elementary level to ensure that students are mastering the standard for their grade level in all foundational skills. That meant the standards that end with that grade level or ended the grade level before. The reason for that if because it is a skill they need to understand in order to make sense of the standards and skills that follow. If the students does not have that mastered then they will be struggling with every related standard until that hole is filled. That does not mean that you only teach the foundational skills to mastery those are just the absolute “must know” standards. All grade level standards should be taught to mastery in a perfect world. Even if the students do not reach mastery of all standards they should at least be on their way towards mastery.

I explain to my students that it is like playing a sport there are very few people who can just play a sport without any instruction and be to join a team and win a game; it takes dedication, practice and a lot of failure in order to become a good player in any sport. Education is no different from learning a hobby, sport, or other skill. You start with the basics and you do it until it is automatic then you push forward to the next step and you practice until it is automatic and fully understood, then keep doing this until mastery is reached. Mastery is reached when a student can successfully demonstrate the standard or skill and they can also teach that standard or skill to someone else. Just because we say we teach mastery based learning it does not mean that it is actually done in a way that is successful to students learning. I can say i have flexible seating because I moved a desk into the hallway, but does that really help that student?

Jennifer & Kareem,

I was sent your podcast by a former colleague with whom I collaborated often at an international school. I haven’t stopped listening to your podcasts! I am hoping to look at this year of distance learning and covid as much needed disruptor. Our world is changing, and we need to make progress in education. The mastery, self-paced classroom is a tangible way to make this progress. It also leads us to more equitable classrooms. I find myself excited to start SY 2021-22 (I’ve never said that in June before!). I just want to say how grateful I am for the willingness from both of you for sharing your platform and making it incredibly accessible (Jenn, for your podcasts and blog…Kareem, for your Modern Classroom course that I started today!). You are change-makers! I found myself left with the question, “Should I plan units separated by content area, or should I go big and try self-paced thematic units based on units of inquiry?” I should note I am an elementary teacher! Keep up the incredible work, you are being heard!

Ty

Ty, we’re so happy to hear you’re enjoying the podcasts and finding value in Cult of Pedagogy resources. I’ll make sure Jenn sees this!

Hi, Kareem!

What a refreshing view and form of instruction. I have been on a bit of a mission lately to discover new ways of instructing students that align with a more student-centred approach. I have come to realize that I can’t keep waiting for the system to change, but rather I have to change in ways that allow for innovation while meeting district and provincial standards.

I really appreciate that this method allows for flexiblity and deviation. I have one question in regard to the four Curricular Conceptions which are: Society-based (focus on social reform), Academia-based (revolving around specific subjects) , Student-centred (focuses on the needs and concerns of the individual students) and Technological-based (more concerned about the systemic delivery of content than the content itself). Regarding these conceptions, would you say that the Mastery-Based approach is still based on Academia, since there is not much deviation in the content itself, just the way that it is being delivered?

As for assessment, I appreciate the incorporation of self-assessment and consistent feedback in this model. The instruction itself would be more about facilitating and checking-in, making sure that students are progressing adequatly, and creating resources and lessons that they can move through. This question may sound silly, but what if a student just simply doesn’t master a skill? For example, I have students that may need to work on fractions for an entire year before mastering the grade-level skills. How would you approach this issue keeping in mind the state or provincial-wide expectations for student learning over the course of a year?

Thank you so much for such a thought-provoking article, and a method for teaching that made me ask “how and why haven’t all educators heard of this?”

As a paraprofessional, I follow in the teacher’s footsteps when he implements everything learned in this module, thus helping students in the progress of the knowledge acquired in the classroom.

It appears that our district is headed in this direction. I have several questions and concerns, but here are two that I find pressing:

1) If students are moving at their own pace, how do you prevent having to write 65 different lesson plans per day?

2) If students are to keep practicing a particular skill until mastery, how do you come up with potentially 180 ways to test the same skill?

(BTW: I am a high school ELA teacher; 20 years experience.)

Jason, these are great questions. If you scroll up and take a look at the end of the section Stage 2: Demonstrating Mastery through Mastery Checks, Kareem has some helpful suggestions for managing assessment and reassessment. You may even find it helpful to check out the ELA mastery check example he’s hyperlinked.

Also, I would recommend reading Kareem’s 2020 guest post, How to Create a Self-Paced Classroom if you haven’t already. If the post itself doesn’t fully answer your questions about planning for a self-paced classroom, Kareem links to his free online course near the end of the post, as well. I hope this helps!

Thanks for the reply Margaret. I checked out the linked post, and I ended up with even more questions. For example, most of the graphics seem elementary-based. Is this a single that this is a program meant for younger learners that is being shoe-horned into secondary?

Also, reading the description of how the classroom works sounds like the teacher just runs around from student-to-student trying to keep them on task. (educational whack-a-mole) I cannot imagine that kind of chaos is conducive to learning. How is that handled?

The idea of self-pacing within units makes sense, but you would still have students falling further behind when they have to move on to a new unit without being exposed to all the material in the previous unit? At what point do you hit diminishing returns?

Jason, these are all interesting questions. We will reach out to the guest author, Kareem Farah, and see if he has a moment to chime in and help you out!

This was a wonderful post to read. With a little over a month away from the beginning of the new school year, I find myself questioning how I will implement my universal rubric for projects in a way that promotes mastery and real-world applications. I was wondering if there are any recommendations on how to introduce this concept in a way that would be conducive to project-based learning?