Listen to the interview with Emily Kircher-Morris (transcript):

Sponsored by foundry10 and SchoolAI

I didn’t realize how much executive functioning teaching required until I ran out of it. The lesson plans, remembering when to send kids to their individual support programs, and trying to keep up with the never-ending pile of graded papers seemed like it wouldn’t be a big deal when I was a new teacher. But underneath, I was constantly juggling, improvising, and frantically trying to stay above water. At the time, I didn’t realize how much my ADHD was impacting me; I just knew that what seemed easy for other teachers sometimes felt like an insurmountable task.

I was “lucky” in some ways that I was diagnosed with ADHD when I was a kid. I was actually diagnosed in fifth grade, back in the early 90s (which for women my age was pretty rare). But that didn’t mean I had much self-understanding or support. As more conversations about adult neurodivergence have surfaced in recent years, I began connecting the dots and realizing it wasn’t just me — being an educator can be really hard for neurodivergent people.

Neurodivergent educators, like those with ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and other forms of cognitive diversity, are essential voices in our schools. We bring innovation, empathy, and authenticity. Yet we often work within systems that weren’t built with us in mind. Recognizing and supporting the needs of neurodivergent teachers doesn’t just benefit those individuals … it strengthens entire school communities.

The “Lost Generation” of Neurodivergent Educators

Many teachers in their 30s, 40s, and 50s grew up in a time when conversations about neurodiversity simply didn’t exist. ADHD was often associated only with hyperactive boys. Autism was narrowly defined and usually diagnosed in early childhood. Girls, high achievers, and those whose behaviors weren’t outwardly noticeable were frequently overlooked.1 2

For many educators, the realization of their own neurodivergence comes later in life. Sometimes this is after their children receive diagnoses, or it might be through finding social media posts or podcasts that have brought more awareness to the diversity of how ADHD, autism, and related profiles can present. This “lost generation” of neurodivergent adults suddenly has language for lifelong patterns of overwhelm, inconsistency, and burnout.

For those who’ve spent years inside schools, the irony is striking: We were trained to spot these traits in our students, but not in ourselves. We learned to collect data, document behaviors, and write interventions, yet rarely paused to wonder why we were staying up until midnight reinventing lesson plans or struggling to follow through on paperwork deadlines. For many, the moment of recognition arrives with equal parts relief and disorientation.

The awareness can bring immense relief (“Oh, that’s why…”) but also grief surrounding the decades spent self-blaming or wondering why things felt harder, and for the unnecessary exhaustion that came from trying to keep up with expectations designed for different brains.

That process of reinterpreting your own story can be both liberating and destabilizing. It changes how you view your work, your students, and the systems you’ve been operating within.

At the same time, these realizations collide with systems that still expect educators to be endlessly adaptable and organized. Despite increased awareness, stigma remains. Admitting difficulty with executive functioning, attention, or sensory regulation can feel risky in environments where “having it together” is equated with professionalism. Even today, many teachers remain quiet about their neurodivergence, afraid it could be misinterpreted as incompetence.

The Strengths Neurodivergent Educators Bring

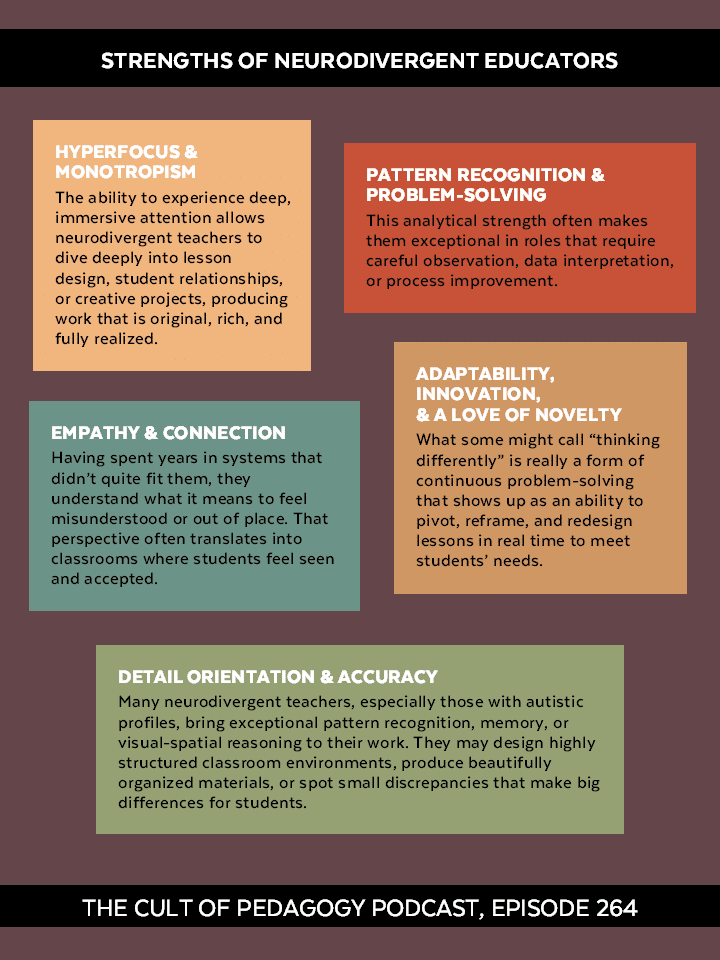

Neurodivergent teachers are often among the most creative, empathetic, and passionate educators in the building. The very traits that make us different are often what make us effective. When we stop viewing neurodivergent traits as deficits and start recognizing them as variations in how we think, process, and engage, we begin to see just how much these educators contribute to their schools and communities.3

- Hyperfocus and monotropism: Neurodivergent educators often experience deep, immersive attention, sometimes described as hyperfocus or monotropism. Hyperfocus, often associated with ADHD, refers to intense concentration on a single task or idea for extended periods, often to the point where time and surroundings fade away. Monotropism, a term used to describe a common cognitive style in autism, involves focusing one’s attention on a limited number of interests or topics with exceptional depth and sustained engagement. In the right environment, both forms of focus become incredible assets. Teachers with these traits can dive deeply into lesson design, student relationships, or creative projects, producing work that is original, rich, and fully realized.

- Pattern recognition and problem-solving: Neurodivergent educators may excel at noticing patterns and inconsistencies, whether in student behavior, curriculum design, or systemic routines. They can detect underlying causes of problems rather than just surface symptoms. This analytical strength often makes them exceptional in roles that require careful observation, data interpretation, or process improvement. What might look like “rigidity” from the outside is often precision and a deep drive for consistency that keeps classrooms running smoothly.

- Empathy and connection: Neurodivergent teachers frequently bring the empathy that comes with lived experience to their interactions with students. Having spent years navigating systems that didn’t quite fit them, they understand what it means to feel misunderstood or out of place. That perspective often translates into classrooms where students feel seen and accepted. These teachers can build strong, trusting relationships, especially with students who struggle with behavior, attention, or social connection, because they understand those challenges from the inside.

- Adaptability, innovation, and a love of novelty: Years of developing coping strategies and creative workarounds can make neurodivergent teachers remarkably resourceful. Many thrive on novelty and the spark that comes from trying something new or approaching a familiar problem in a different way. That curiosity often leads them to experiment with tools, routines, or technologies that make learning more engaging and accessible for everyone. What some might call “thinking differently” is really a form of continuous problem-solving in the form of an ability to pivot, reframe, and redesign lessons in real time to meet students’ needs. Their willingness to embrace change and explore new ideas often brings fresh energy to their classrooms and to the teams they work with.

- Detail orientation and accuracy: While not every neurodivergent teacher thrives on details, many, especially those with autistic profiles, bring exceptional pattern recognition, memory, or visual-spatial reasoning to their work. They may design highly structured classroom environments, produce beautifully organized materials, or spot small discrepancies that make big differences for students.

These are only a few of the strengths that neurodivergent teachers bring to their work. When educators feel safe to show up as themselves, these traits flourish rather than get buried under masking and exhaustion. They model authenticity, self-awareness, and creative problem-solving for their students, reminding everyone that there isn’t one “right” way to learn, think, or teach.

When Systems Don’t Fit Neurodivergent Teachers

Still, those strengths exist within structures that can easily drain them. Schools are built on routines and expectations created for the neuronormative majority, including an ability to transition quickly, multitask seamlessly, and tolerate a constant stream of sensory and social input. For neurodivergent educators, these same environments can quietly chip away at energy, focus, and confidence over time.

- Executive function overload: The cognitive load of teaching is enormous. Lesson planning, grading, emails, hallway supervision, meetings, and parent communication all compete for mental bandwidth. For ADHD teachers, who thrive in bursts of novelty and urgency, the ongoing demand for sustained organization and follow-through can be exhausting. What looks like inconsistency from the outside is often a byproduct of a brain working overtime to juggle competing priorities without enough recovery time in between.

- Sensory and environmental stressors: Schools are not quiet places. The hum of fluorescent lights, the echo of the cafeteria, the unpredictability of fire drills, and the constant motion of students in transition can become overwhelming for educators with sensory sensitivities. Autistic and other neurodivergent teachers may spend a significant portion of their energy simply filtering sensory input enough to function. By the end of the day, the fatigue from that invisible effort can rival the exhaustion of running a marathon.

- Social expectations and masking: Beyond the classroom, teaching involves navigating staff dynamics, parent interactions, and unspoken workplace rules. For educators who find social nuances challenging or draining, this can feel like performing a second full-time job. Many neurodivergent teachers learn to camouflage or mask their differences by consciously imitating social behaviors or communication styles that don’t come naturally in order to fit in or avoid judgment. Masking can be protective, but it’s also exhausting, leading to disconnection and burnout over time.

- Perfectionism and burnout: Neurodivergent educators often hold themselves to impossibly high standards, a trait fueled by years of internalized messages that they must prove their competence. The drive to overperform and be the “organized one,” the “dependable one,” the “creative one,” can keep them running long past healthy limits. Eventually, that overcompensation gives way to burnout, where even a teacher’s favorite parts of the job begin to feel impossible.

- Systems that don’t fit: Individually, each of these challenges is taxing. Together, they create a mismatch between the neurological realities of neurodivergent teachers and the systems they’re asked to operate within. Schools often celebrate innovation and dedication but rely on rigid structures that punish variability in focus, energy, and communication. Without intentional redesign, the system quietly weeds out the very educators whose strengths could transform it.

Neurodivergent educators show many of the very qualities schools say they value most. Yet those same traits often exist in tension with the rigid structures of school life. When flexibility and understanding are missing, strengths become stressors. The paradox isn’t in the teachers themselves, but in the environments that celebrate differences in theory but struggle to support them in practice.

Practical Tools and Strategies for Neurodivergent Educators

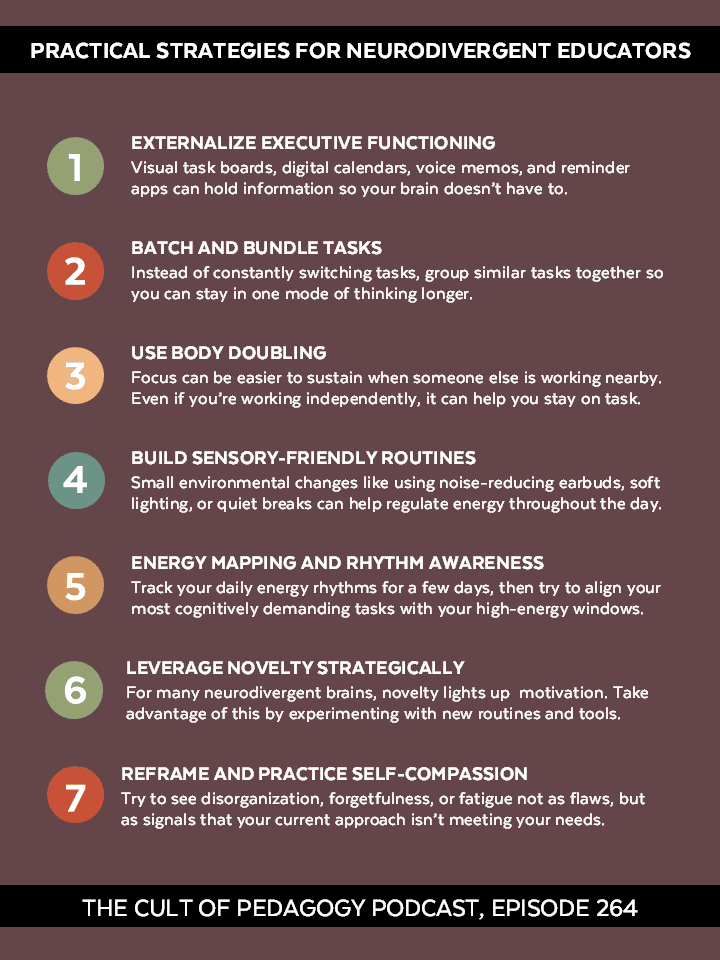

While systemic change is essential, there are strategies neurodivergent educators can use to protect their energy and make the job more sustainable. None of these approaches are one-size-fits-all, and what helps one person may not work for another. However, experimenting to find the right combination can make a meaningful difference in daily functioning.

1. Externalize Executive Functioning

Teaching requires juggling hundreds of small decisions every day, and relying on memory alone is a recipe for overwhelm. Offload those mental tasks onto systems you trust. Visual task boards, digital calendars, or reminder apps can hold information so your brain doesn’t have to. Some teachers use voice memos to capture ideas on the go or automation tools like If This Then That to streamline routine tasks (for example, automatically filing certain emails or setting recurring reminders). The goal is to make the invisible visible and to move mental clutter into tangible, manageable form.

2. Batch and Bundle Tasks

Neurodivergent brains often lose momentum with constant task-switching. Try grouping similar tasks together so you can stay in one mode of thinking longer. You might set aside a block of time to grade all short-answer responses at once or write lesson plans for the entire week in one sitting. Reserve another time for communication tasks like emails or parent updates. This reduces cognitive “gear-shifting,” which can be one of the most draining parts of the job.

3. Use Body Doubling

Focus can be easier to sustain when someone else is working nearby, a concept known as body doubling. Partner with a colleague for shared planning periods, or hop on a virtual co-working session. Even if you’re working independently, the accountability of another person’s presence can help you start and stay on task. Some teachers use this strategy for grading or report-card season, while others find it helpful for daily planning.

4. Build Sensory-friendly Routines

Small environmental changes can have a big impact. If noise is a trigger, use noise-reducing earbuds or soft background sound. Adjust lighting when possible. Lamps or natural light often feel gentler than overhead fluorescents or LEDs. Incorporate short movement breaks, stretching, or grounding activities between classes. Many teachers benefit from having a small “reset ritual,” like stepping into the hallway for a few breaths or sipping water between transitions. These small, intentional resets can help regulate energy throughout the day.

5. Energy Mapping and Rhythm Awareness

Every brain has patterns, including times of day when focus and energy peak, and times when they fade. Try tracking your daily rhythms for a week or two, noting when tasks feel easiest and when you tend to hit a wall. Then, as much as your schedule allows, align your most cognitively demanding work (like lesson planning or feedback) with your natural high-energy windows. Save lower-energy times for tasks that require less focus. This awareness can also help you plan recovery and know when to pause before you crash.

6. Leverage Novelty Strategically

For many ADHD and autistic brains, novelty lights up motivation. You can harness this by introducing small variations to routine tasks, like experimenting with new lesson formats, rearranging your classroom layout, or trying a new digital tool. The key is to use novelty as fuel, not distraction: Rotate in new ideas when you feel stuck, then return to familiar structures when you need grounding.

7. Reframe and Practice Self-compassion

When the system isn’t built for your brain, it’s easy to internalize frustration as failure. Try to see patterns of disorganization, forgetfulness, or fatigue not as personal flaws, but as information; these are signals that your current approach isn’t meeting your needs. Self-compassion creates space to experiment without shame and to recognize that “professionalism” doesn’t have to mean perfection. Sustainable teaching starts with honoring your humanity.

Together, these tools aren’t about doing more, they’re about doing differently. The most effective strategies are the ones that reduce friction, preserve energy, and let your strengths take the lead.

What Schools and Administrators Can Do

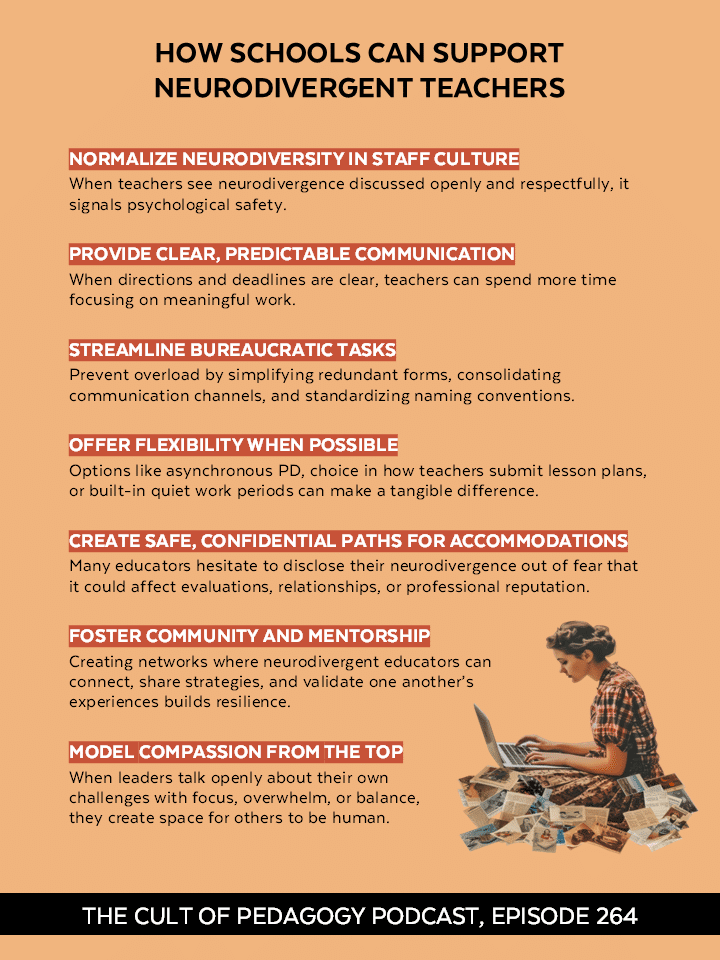

Supporting neurodivergent educators isn’t about special treatment; it’s about equitable access to the profession. Just as we differentiate for students, we can differentiate support for teachers. The goal is not to lower expectations, but to create working conditions where every educator can bring their best self to the classroom without burning out in the process.

- Normalize neurodiversity in staff culture: Inclusion efforts often center around students, but educators benefit just as much from a culture that recognizes and values neurological diversity. Incorporating neurodiversity into professional learning could occur through book studies, PD sessions, or even informal staff discussions with the goal of dismantling stereotypes and stigma. When teachers see neurodivergence discussed openly and respectfully, it signals psychological safety. It gives permission for self-reflection and, for some, the courage to seek support or accommodations without fear of judgment.

- Provide clear, predictable communication: Ambiguity is a major source of stress for many neurodivergent educators. Simple structural supports (such as providing written follow-ups after meetings, sharing agendas in advance, or clarifying expectations in writing) make communication more equitable for everyone. When directions and deadlines are clear, teachers spend less time decoding tone or trying to infer priorities and more time focusing on meaningful work. Predictability doesn’t limit flexibility; it creates stability from which creativity can grow.

- Streamline bureaucratic tasks: Administrative overload drains all educators, but it disproportionately impacts those with executive functioning differences. Schools can help by simplifying redundant forms, consolidating communication channels, and clearly defining who is responsible for which tasks. Digital workflows that automatically organize information or prompt reminders can be a huge relief. Even small tweaks, like consistent naming conventions for shared documents or fewer email threads, can save hours of cognitive energy each week.

- Offer flexibility when possible: Flexibility is one of the simplest and most effective supports schools can offer. Options like asynchronous professional development, choice in how teachers submit lesson plans, or built-in quiet work periods can make a tangible difference. Some neurodivergent educators may need sensory breaks or opportunities to step out of overstimulating environments built into the day. Others might benefit from having input into when to schedule meetings or what time of day they use for planning time. It can be tricky to work some of these logistical changes into the typical school day, but when administrators model flexibility, they communicate trust, and that trust often translates into higher-quality work and stronger relationships.

- Create safe, confidential paths for accommodations: Many educators hesitate to disclose their neurodivergence out of fear that it could affect evaluations, relationships, or professional reputation. Schools can counter that fear by ensuring that accommodation processes are transparent, confidential, and rooted in respect. Train administrators and HR staff to respond to disclosure with curiosity and support, not skepticism. This might include helping teachers identify practical adjustments, like modified communication expectations, lighting changes, or planning space, rather than focusing narrowly on medical documentation. Equitable support should be proactive, not reactive.

- Foster community and mentorship: Isolation amplifies burnout. Creating networks where neurodivergent educators can connect, share strategies, and validate one another’s experiences builds resilience. Mentorship programs that pair early-career teachers with experienced, affirming mentors can make a powerful difference in retention and well-being. Even informal affinity groups or online spaces for neurodivergent staff can cultivate belonging and normalize conversations about working differently. When teachers feel seen and supported, they’re more likely to stay, grow, and contribute authentically to their school communities.

- Model compassion and sustainability from the top: Administrators set the tone. When leaders talk openly about their own challenges with focus, overwhelm, or balance, they create space for others to be human, too. Building a neurodiversity-affirming workplace isn’t just a policy decision; it’s a cultural shift toward valuing transparency, flexibility, and empathy as professional strengths.

It’s Not About Fixing Us. It’s About Fixing the System.

When schools intentionally support neurodivergent educators, everyone benefits. Teachers who feel safe to work in ways that fit their brains are better able to model that same acceptance for students. The classroom becomes a place where difference is understood as part of learning, not something to conceal or correct. Students see adults who use visual schedules, take sensory breaks, or talk openly about their attention patterns, and realize that these strategies aren’t signs of weakness, but tools for success.

The same is true for school leadership. When administrators approach neurodiversity with empathy and flexibility, it builds trust across the staff. Clear communication, reasonable expectations, and genuine openness make it easier for all educators to stay engaged and innovative. A culture that values sustainability over perfection tends to retain its best people, because they’re not burning out trying to meet impossible standards.

As more educators recognize their own neurodivergence, the conversation is shifting. Awareness alone isn’t enough. We need structures that turn understanding into action. Schools that design for flexibility, clarity, and belonging don’t just make life better for neurodivergent staff. They create environments where every teacher and every student can show up fully, knowing they belong as they are.

- Holden, E., Kobayashi-Wood, H. Adverse experiences of women with undiagnosed ADHD and the invaluable role of diagnosis. Sci Rep 15, 20945 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04782-y ↩︎

- A. S. Russell, T. C. McFayden, M. McAllister, K. Liles, S. Bittner, J. F. Strang, and C. Harrop, “Who, When, Where, and Why: A Systematic Review of ‘Late Diagnosis’ in Autism,” Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research 18, no. 1 (2025): 22–36, https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.3278 ↩︎

- Doyle N. (2020). Neurodiversity at work: a biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults. British medical bulletin, 135(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa021 ↩︎

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

LOVED this podcast. Honestly, I’ve been looking at this for a while without naming it. My question, and one area that was not mentioned, is how to help parents be more understanding with their child’s teacher. I’m an administrator, and I love what our neurodivergent educators bring to our community. That being said, not all parents understand the rigidity, or the lack of organization, or “she’s being so neurotic about noises,” or… Any suggestions for how to address this with parents, as I want to respect privacy, but wondering about ideas in that regard. Thank you for sharing your insight!

Such a great question! I think a proactive approach works well: talk early and broadly about how teachers, like students, bring different sensory, organizational, and communication styles to their work. Then, when parents have concerns, scaffold their understanding by connecting what they’re seeing to the purpose behind the teacher’s choices (“this routine keeps the environment calm,” “this structure helps students stay regulated”). It reframes the behavior through a student-centered lens without disclosing anything personal, and helps parents understand the nuance with more empathy. Thanks so much for listening and thinking about this important aspect!

As a neurodivergent administrator, this shed so much light on my struggles as a teacher. Technology has provided tremendous executive function support, but I find that as I age, the masking becomes so much harder.

Such interesting work, and so important. Supporting neurodiversity in our adults improves schools for our learners.

If you’re interested in this topic, read more about how this plays out in a series of articles about neurodiverse leaders in international schools:

Better Together: Neurodiversity in International School Leadership – April 2025: https://www.tieonline.com/article/7640/better-together-neurodiversity-in-international-school-leadership

Diana Rosberg Connects The Dots (Autism) – May 2025: https://www.tieonline.com/article/7649/diana-rosberg-connects-the-dots-autism-

Richard, Deb, and Dyslexia – June 2025: https://www.tieonline.com/article/7648/richard-deb-and-dyslexia?nid=84

Mare Noble Pays Attention (ADHD) – July 2025: https://www.tieonline.com/article/7731/mare-noble-pays-attention-adhd-

Eryn Harnesses Creativity and Passion (Bipolar) – Aug 2025: https://www.tieonline.com/article/7745/eryn-harnesses-creativity-and-passion-bipolar-?nid=86

Bengt Rosberg Senses His Way Forward (Hypersensitivity) – September 2025: https://www.tieonline.com/article/7796/bengt-rosberg-senses-his-way-forward-hypersensitivity-?nid=91

I wanted to bring attention to another type of neurodivergence for teachers: OCD, it is a very complex disorder and very multifaceted. Some struggle with contamination OCD and avoid any staff food days, wash their hands obsessively, and fret about every cough, sneeze, and more. Others struggle with perfectionism OCD, which is different from regular perfectionism in that constant rumination can overtake a mind very quickly.

Here is a quick overview of some different subtypes of OCD.

I personally struggle with OCD focused on norovirus. Some ways it’s impacted my teaching both in the classroom and now as an educational tech coach:

I once sprayed a permission slip with lysol and it ended up so glued to the floor that the custodians had to strip it and rewax it.

I have often avoided staff food days and always throw out any leftovers from any items I contributed to the meal

I have hidden in my office when I know norovirus is in the school and avoided drinking anything so I didn’t have to use the bathroom.

After getting norovirus, I washed my hands obsessively in an effort not to pass it to anyone else. They ended up with raw skin.

I also struggle with perfectionism OCD.

I always worry about how people will perceive me and consider me a failure for most everything I do.

I will ruminate over conversations and their meanings.

I spend extra time to make sure everything is perfect, but mostly so I’m not judged.

I can easily feel shame for so many reasons like “Did I say the right thing?” etc

Keep in mind that OCD affects people in myriad ways. Those of us in treatment are often dealing with Exposure Response Prevention (ERP) and medicine.

It can take years to diagnose and those who aren’t diagnosed might feel that their experiences are “normal” which leads to a lot of stress and coping mechanisms that can actually make OCD worse. Additionally, OCD can flare up, so a person can be managing pretty well and then *boom* all the stress and compulsions start again.

Thank you for sharing this, RC. It may be difficult for people who don’t have these experiences to understand the impact on our lives. Testimonies like yours are rare glimpses into the realities of coworkers we may not even know are dealing with these things. Hoping you are getting the support you need from your school community.