Listen to the interview with Blake Harvard:

Sponsored by Listenwise and Khan Academy Kids

Please allow me to describe an all-too-common situation that has occurred in probably every teacher’s classroom: You teach your heart out. Really just knock it out of the park: explaining, describing, providing examples, modeling … you know, all the things we’re taught to do during instruction. Then you ask what you believe is a simple question all students should know the answer to … and … nothing. Absolute crickets. You sheepishly look out into the abyss that is your classroom and you see it.

The blank stare.

It can be momentarily debilitating. What to do? Just restate the question again? Maybe they didn’t hear the question. I’ll just say it again. Yeah, that’s it. (That, in fact, isn’t it.)

Why aren’t they answering my question?

Why don’t they know this content?

I just taught it to them.

They should know this.

Any of this sound familiar? I think, if we’re being honest, all teachers have experienced a very similar scenario. What went wrong? Why don’t they know this stuff I just taught? It can be very frustrating, sort of spinning your wheels and getting nowhere with student learning. Below are four possible explanations from cognitive psychology to explain this occurrence, followed by some possible solutions.

Explanation 1: Inadequate Schema Development

The students in your classroom are, more than likely, novices when it comes to this new content. Novice and expert learners experience and process information differently. Novices probably do not have a lot of background knowledge on the subject and, therefore, have a poorly developed schema for the content being taught.

I like to think of schema development like a spider web: The more connections to the information being taught, the more complex the spider web of knowledge. And, just like a real spider web, the more connections to the information, the easier to catch bugs (or, in our case, new information). Basically, it is much easier to add information to already established and understood information in memory. But when novice learners experience new information, they have a minimal spider web, so they struggle to ‘catch’ new content. So, even though you may have introduced the new material well, students may still struggle to process all of that new information.

Solution: Access Background Knowledge and Relevant Schemas

It always helps to access background knowledge in class. This is especially important when beginning a new topic. Any activities attempting to relate the content to the students is also an effort at accessing their ‘spider web of knowledge’ and gives them a better chance of ‘catching’ the new material. Unless students have direct knowledge of the information, they probably won’t unconsciously or consciously think to themselves, “Oh, this directly/indirectly relates to a similar topic that I do know something about and I should view this new material through a lens of what I already know and understand.” Explicit attempts in class to access that background knowledge and, consequently, the spider web will help with schema development and a better understanding of the new material.

I mostly do this in class through a quick pretesting of information, usually either a few questions or prompts about the content to get the students thinking about what they already know. I emphasize to the students that this pretest assessment isn’t for a grade and is much more of a way to prime your memory for the new information. I invite any and all discussion and questions from students during this time. It appears pretesting prepares the brain for the upcoming lesson and accesses the spider web of knowledge they may already have in memory.

Explanation 2: Limited Working Memory

Following the same line of thinking as above, novice learners’ working memory (which is a necessary but insufficient aspect of memory processing for long-term retention) is very quickly overloaded with information. When working memory is overloaded on the path to long-term processing, memory suffers greatly.

It’s a bit like someone being given five tennis balls to carry across a room to place them in a box. Just five tennis balls? That may be fairly easy. But if I gave you fifteen to carry, you’d probably lose most of them while crossing the room. When the novice student is required to ‘carry’ multiple bits or chunks of content in their working memory at any one moment, it can become very overwhelming and they may not even process any of the information. More practically, this may show up in a math teacher showing students how to solve a problem with multiple steps. If the students are unfamiliar with the first steps, they will be overloaded with that information, probably become flustered, and either give up or have no chance of processing the steps further into the problem.

Solution: Chunk the Learning

Again, since the novice learner’s working memory is easily overloaded with new material, it really helps to break down new content into much smaller chunks of information for cognitive consumption. And, while teachers certainly already know this to be true, I know I sometimes underestimate just how small those chunks may need to be. Research by Cowan in 2010 showed evidence that four chunks are about all we can process in working memory at any one time. That is quickly depleted, however, if we don’t have well-established schemas for the material. So make sure those chunks are small and, with multistep problems and/or concepts, make sure students are assessing their progress on the first steps before attempting to move to the next steps.

Explanation 3: The Curse of Knowledge

Teachers are the best/the worst at displaying one particular cognitive bias: the curse of knowledge. Basically, the curse of knowledge rears its ugly head when someone assumes that others should know the same information they know. In the classroom, this occurs when teachers assume students should know and understand the content because they just told them about it in class or they discussed it yesterday in class. Even if they understood it yesterday, a lot of forgetting can happen in twenty-four hours.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I have been in the classroom for eighteen years, so I completely sympathize and understand that students do not always pay attention in class and this will definitely lead to them not understanding material. However, I know that in the past, I have been guilty of thinking to myself, “Why don’t they know this stuff? It makes sense to me.” That is the curse of knowledge. Now, whenever I start to feel this way, I think about how many times I’ve taught this material and how sophisticated my schema is for this content. Most of my students are hearing this material for the first time. Of course, it seems logical that they would struggle a bit more than me.

Solution: Empathize with Students

The best way to overcome the curse of knowledge is to empathize with students. It helps to try to put myself in their shoes and think about how flustered and how foreign I would feel as a student if they were teaching me something that they care deeply about, like some new dance on social media or the nuanced meaning behind Taylor Swift’s latest dis track about one of her ex-boyfriends. I wouldn’t remember most of it and that’s okay. It should also be okay for our students to not know or understand information in class after coming into contact with it for the first time. That empathy often helps me with being much more understanding with my students and I become more patient with reviewing material before moving on to newer content.

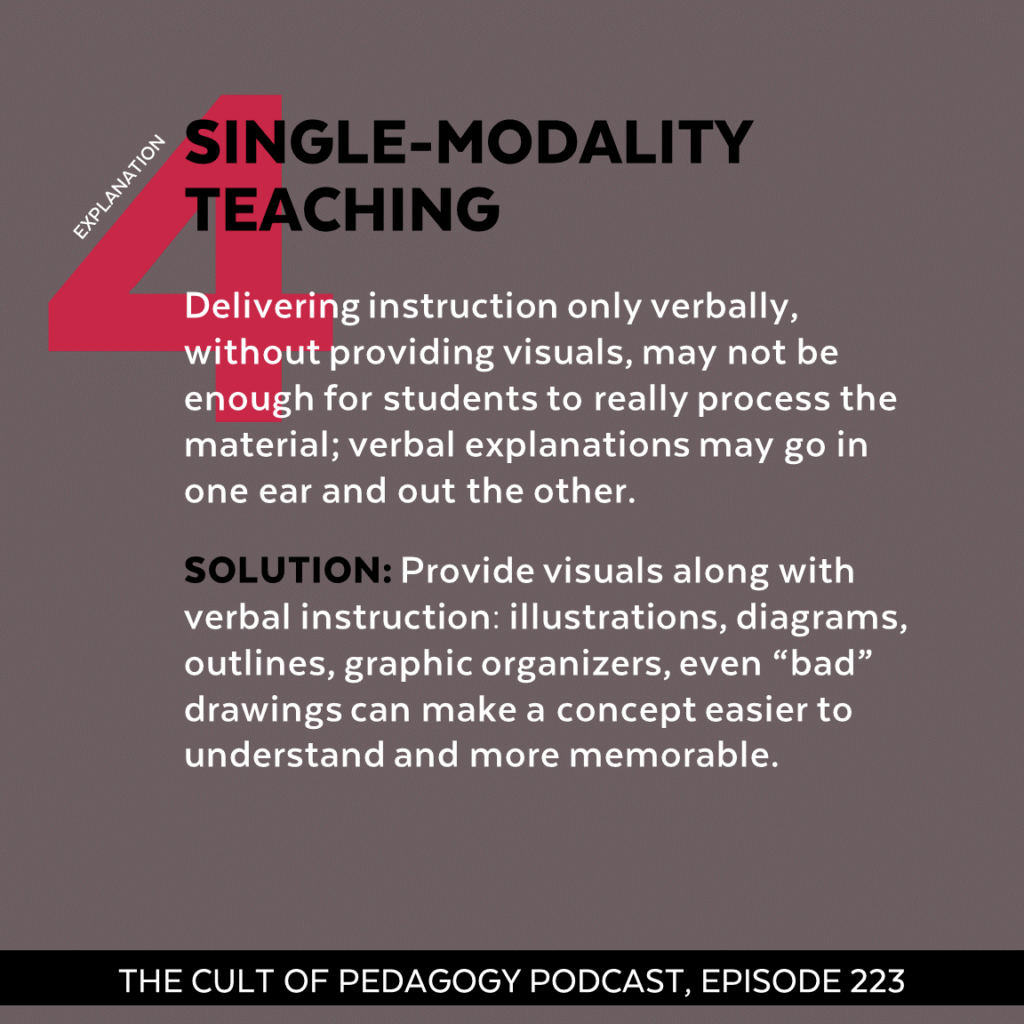

Explanation 4: Single-Modality Teaching

Probably, as a result of experiencing the curse of knowledge, teachers then also forget to provide instruction in multiple modalities for easier processing of information. (This is absolutely not a nod to teaching to preferred learning styles … don’t do that.) Again, if it seems easy to me, maybe a verbal explanation of the topic or concept will suffice for my students? That may not be the case. Spoken words may not be enough for students to hold that information in working memory long enough to really process the material. The content may need something to latch on to or it is in one ear and out the other.

Solution: Anchor Information with Dual Coding

Rather than simply talking through a lecture of new content, providing visuals is a fantastic way to assist learners with a kind of anchor for the material. In cognitive psychology, this is a kind of dual coding of information. Dual coding adds to the context of the material. Generally speaking, the more context that can be added to the instruction, the more connections can be added to that spider web of knowledge.

And whether the teacher provides a simple illustration or the students provide their own, don’t worry with the ‘but I’m not a good artist’ excuse. The quality of the drawing or picture has nothing to do with its ability to help with processing. In fact, I tell my students that sometimes the drawing that is humorous in its execution can be better for remembering. I’ve heard students say that they remembered a concept because their drawing was so bad. That made it stick out in their memory and aided in the processing of the information.

And it doesn’t necessarily have to be a drawing or illustration. Other memory aids — such as graphic organizers, mind maps, and hierarchies — all allow students to visualize the content and add context to the material, making it easier to mentally organize information in memory.

Are these solutions foolproof? Will they always account for every experience of ‘the stare’? Of course not. As you well know, there are no silver bullets in education. Nothing works all the time with all students, and anyone who tells you so is either quite misinformed or is trying to sell you something. But understanding that learners are novices when experiencing new information and that impacts their ability to process that material is important. And knowing that just because the content is easily understood by myself does not mean it is comprehended and remembered by my students is also important.

The stare isn’t fun for anyone in the classroom. Teachers don’t like feeling like they’ve wasted their time with instruction and students do not like to feel like they’re not learning the material. Identifying possible reasons for this happening and working to remedy them should decrease ‘the stare’ and help to create a more efficient, effective, and motivating classroom.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Can’t help remembering the reverence with which “learning styles” were proselytized in the ’80s. My school at the time even invited the Dunns, the author couple of the original book, to speak at a p.d. day. Not all the ideas are bad and should just be considered more tools in your toolkit, but every new idea is said to be research-based and the methods are often imposed on teachers across the board to the detriment of our lessons.