Listen to the interview with Laurie Rabinowitz and Amy Tondreau (transcript)

Sponsored by Alpaca and The School Me Podcast

This page contains Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

Over the past few decades, significant strides have been made in the field of special education to make every classroom a place where students, regardless of ability or disability, can reach their full potential. Most of that work has been driven by a focus on access — working to ensure that students with disabilities aren’t left behind academically. And while this is obviously an important goal, it has sometimes been viewed through a deficit lens, where there is one default way of doing school, and then there are strategies for helping students with disabilities fit better into that default way. While these efforts have succeeded in improving access, they still position disabled students as lacking in some way.

What’s been missing is an approach that affirms and sustains disability as a source of identity and pride.

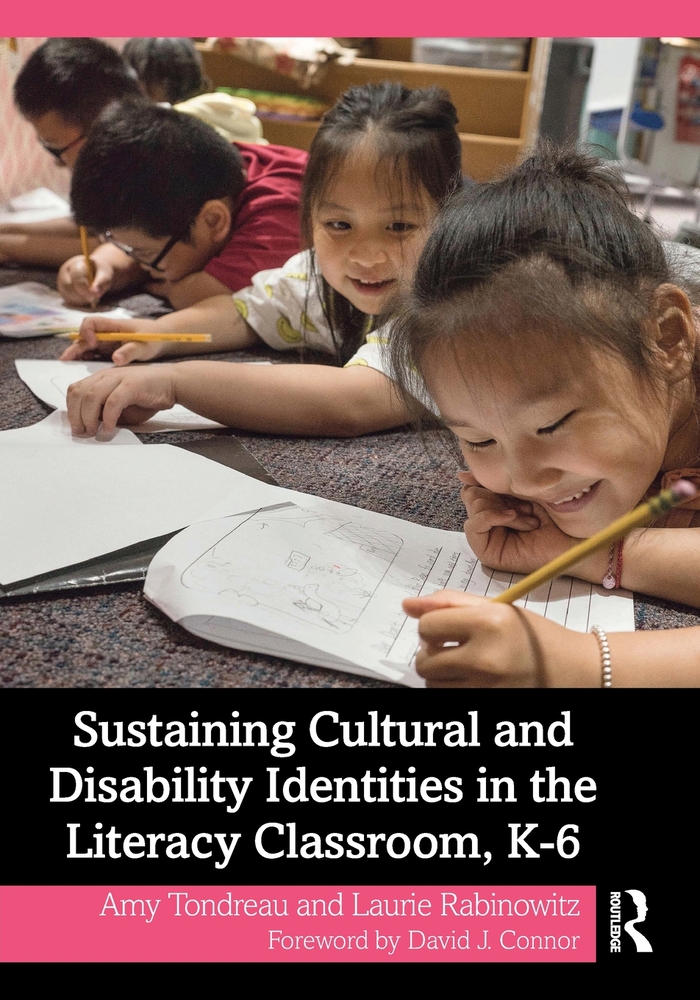

That’s the focus of my conversation with Amy Tondreau and Laurie Rabinowitz, authors of the book Sustaining Cultural and Disability Identities in the Literacy Classroom, K-6. Drawing from their own experiences as educators, as well as the voices of over 20 classroom teachers, their work explores the concept of disability-sustaining pedagogy, an approach that goes beyond access to help students with disabilities take pride in who they are. While the book focuses primarily on literacy instruction at the elementary level, it offers valuable insights and practices for anyone who teaches or works with disabled students.

On the podcast, we talk about how this idea builds on the framework of culturally sustaining pedagogy, what it means to treat disability as a cultural identity, and the specific things teachers can do to create classrooms where disabled students feel, as Tondreau puts it, “fully seen and fully known.” You can listen in the player above, read the transcript, or take a look at the summary below.

Background and Overview of Disability-Sustaining Pedagogy

The framework for disability-sustaining pedagogy builds on the work of Gloria Ladson-Billings, who introduced the idea of Culturally Relevant Teaching, and Django Paris and Samy Alim, who expanded that into Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies.

Culturally sustaining pedagogy, Tondreau explains, “asks us to think about lots of different identities — racial identities, linguistic identities, religious identities — and disability is often included in that list. However … it was rarely taken up in concrete examples. So when we were seeing research studies or classroom examples of culturally sustaining pedagogy, they tended to focus on race or language or culture, and disability wasn’t sort of fleshed out. And so we really started to think about what would it look like for us to treat disability as a cultural identity that was worthy of being sustained. Because so often in schools, we’re still relying on a medical model of disability. We need to switch from a deficit lens — what’s wrong with these kids — to an asset lens — what’s right with these kids. And so really thinking about how do we sustain the cultures of disability and disabled ways of knowing and being.”

To fill that gap, Tondreau and Rabinowitz followed Ladson-Billings’ approach of learning from teachers who shared the same identities as the students they served. They drew from interviews with disabled teachers and developed a framework with three key tenets:

- Moving beyond access to a focus on cultural identities

- Helping students identify disabled adults who have learned how to leverage their talents

- Thinking about how non-disabled people can learn from disabled ways of knowing and being

They recommend the following practices for building disability-sustaining classrooms.

Practices that Affirm and Sustain Disability Identity

1. Disability-Affirming Dialogue

One of the most powerful things teachers can do to be more disability-sustaining is to create space for students to talk about their own identities; this includes their disabilities.

“You can be talking about that cultural identity,” Rabinowitz explains, “you can also be talking about the diverse ways that a neurodiverse brain might work or an interesting, cool, complicated body might work.”

These conversations don’t just affirm students with disabilities; they deepen everyone’s understanding of how learning happens. “It’s kind of like a ‘how we learn’ type of instruction,” she says, “and then use that to create the toolbox of scaffolds that exist in your classroom.”

But this kind of dialogue must be built on trust. Not every student is eager to talk about their identity, and that’s okay. “Some students are in the middle of a whole class lesson raising their hand, jumping in … they want to share about those identities,” says Tondreau. “Other students don’t feel comfortable with that. So part of it is building relationships with your students and knowing who feels comfortable with what.”

For students who don’t want to talk directly about their disability, the conversation can still happen more broadly. “In disability-sustaining classrooms, that’s sort of an ongoing conversation for everybody,” Tondreau says. Students reflect together on what strategies support their learning, what tools help them focus, and what challenges they’re facing, without anyone being singled out. “By folding in those ongoing conversations,” she explains, “it becomes sort of a normalized part of the conversation, just like we’re talking about the content that we’re learning or the skills that we’re learning.”

2. Choose or Modify Materials for Disability Representation

In most classrooms, disability is either invisible or reduced to a single token example — often a historical figure like Helen Keller. To be disability-sustaining, teachers need to go beyond single examples. “Very often, disability is invisible in curriculum,” Tondreau says. “Or there might be one text. But there’s very little contemporary representation that shows disabled people sort of going about their everyday life.”

One way to address this is to include more books by disabled authors. “Books like Good Different by Meg Eden Kuyatt or El Deafo by Cece Bell show characters in their everyday life in contemporary settings,” Tondreau says. “Bringing voices of disabled authors into your classroom is a way to give those identities space in the curriculum.”

Even if you’re locked into a scripted curriculum, you still have options. “If that’s the situation you’re in,” Tondreau says, “one of the ways you can invite disability representation into your curriculum is inviting students to rewrite or remix text.” Drawing on remix practices from social media, like dueting TikToks or stitching Reels, teachers can encourage students to rework existing texts to make them more inclusive.

They’ve even done this with phonics materials. “Oftentimes phonics curriculum comes with sound cards that include guide words,” Tondreau says. “Including photographs of your students making those [sounds]…asking your students what the guide words could be,” can make the materials far more reflective of your classroom’s real diversity.

3. Create Affinity Clubs or Mentoring Programs

“Many of the folks that contributed to this book cannot name someone in their life that was a mentor for them as someone with a disability who also had a disability,” Rabinowitz explains. “And many of them cannot name a disability community that they’re a part of.” These kinds of relationships, she argues, are essential not only for learning, but for belonging.

Schools can help fill this gap by creating intentional opportunities for connection. “You can create affinity clubs in schools or mentoring programs,” Rabinowitz says, “where an educator with a disability or an educator who’s an ally to students with disabilities can have a space together where you talk about disability community, culture, pride.”

Even student government can get involved. “You can have opportunities on a student government…for a representative for disability access,” Rabinowitz suggests. “Who’s the 504, ADA, IDEA representative on student government?” Just as schools have roles for athletic or academic leadership, they can carve out space for disability advocacy, too.

These structures aren’t just about support; they help normalize disability as an identity students can claim with pride. “We want students with disabilities to be able to come away as an adult and say, this was someone who mentored me,” Rabinowitz says, “and this is a community that I’m a part of and I continue to be a part of as an adult because it sustains me.”

4. Offer Alternative Processes

Disability-sustaining teaching means recognizing that the same support strategy won’t work for every student, and offering flexibility in how students learn and demonstrate their understanding.

Graphic organizers, for example, are a widely used tool in special education, but they don’t help everyone. One autistic educator explained to Rabinowitz that because of her cognitive inflexibility, the open-ended nature of a graphic organizer actually made writing harder. Rather than requiring the same tool for all students, this teacher now gives a range of checkpoint options: Some students still use organizers, while others might submit polished paragraphs or share their thinking in a conversation.

This kind of flexibility can be especially helpful for students with anxiety or ADHD, for whom rigid processes may increase stress or create additional barriers. By offering varied, responsive pathways and listening closely to student feedback, teachers can create classroom systems that work with students’ strengths instead of against them.

5. Listen to and Partner with Disabled Educators and Community Members

People who can share their lived experience with disabilities can deepen everyone’s understanding of disability not just as a condition to accommodate, but as a cultural identity shaped by unique ways of thinking, learning, and moving through the world. Their insights can help shift mindsets, enrich curriculum, and inform more inclusive school practices.

Even if no disabled educators are available locally, teachers can still learn from disability communities by turning to literature, which can include children’s books. “[Children’s] books can be useful no matter the grade level that you’re working with,” Rabinowitz says. “They often tell stories of what it’s like to be in school as a student with a disability. And because they’re written by disabled authors, they can teach us a lot about those authentic experiences.”

The books below are a few that Rabinowitz and Tondreau recommend for expanding our lens on disability identity.

What would it look like if more classrooms start to implement these practices? “We would talk about disability in a way that isn’t connected to shame,” Tondreau says. “There are teachers and students who are trying to hide this part of themselves because they feel like it’s something that’s shameful, and it’s not. I think if we were really doing this work, if we had disability sustaining classrooms, those teachers and students would feel fully seen and fully known and feel like that part of them is valued.”

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.