Listen to the interview with Jennifer Serravallo and Kelly Cartwright (transcript):

Sponsored by EVERFI and Verizon Innovative Learning HQ

This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

I have been running Cult of Pedagogy for over 10 years now, and in that time there have been a few topics I have learned to steer clear of, because they incite so much heated debate and I don’t feel equipped with enough background knowledge to respond in an informed, responsible way. Near the top of that list is reading instruction, the question of how we should be teaching young children to read. Any time we got even slightly close to that topic, the vitriol that emerged on social media was enough to make me never want to touch that hot stove again.

Some quick background on me: My experience is in English language arts for grades 6 through 12. I have no training in teaching early literacy, but I was an early reader myself, and I taught all three of my children to read before they started kindergarten. Despite my lack of training, I just intuitively did this using foam toy letters and a set of books called Pup and Pop. Because I had already taught my kids how to decode, I had no idea how those skills were being taught in their primary classrooms; I still don’t know. Had I not taken those steps, I might have noticed what some parents across the country were also noticing — that their kids were not learning to decode words — and I probably would have been far more vocal about this on my own platform.

Since that was not the case, I’m just getting up to speed now, and I’ve asked for help from someone whose approach to literacy has always seemed grounded, nuanced, and reasoned. Jennifer Serravallo has written over 15 books and other resources about literacy instruction. In 2018, she joined me on the podcast to clear up some of the confusions and misapplications of leveled texts. When I asked her to come back to talk about the debate on reading instruction, she asked if she could invite another guest to join us. Since Jen considers herself a practitioner who has steeped herself in the research, but not a researcher per se, she wanted to be joined by someone whose background and expertise complements hers. So we will also be talking with Dr. Kelly Cartwright, a researcher and university professor in the fields of cognitive science, neuroscience, and teacher preparation.

Our conversation started with some background on what the main parts of the debate are and how we got here. Then we shifted to a discussion of what research says teachers should be doing to ensure that all kids can build strong reading skills in the early years. You can listen to our full conversation in the player above, read the full transcript, or read my summary below.

Two notes:

- We made the decision to not name any specific authors, educators, publishers, or journalists whose names have been a common focus in recent media coverage. Instead, we talked in generalities based on the science of reading. Our goal is to help teachers, parents, school leaders, and policymakers extrapolate the most effective practices, not get bogged down in who is right and who is wrong.

- We didn’t mention the first edition of Jen’s very popular book, The Reading Strategies Book, which was originally published in 2015. That edition includes 300 strategies to support many aspects of reading — from fluency to comprehension to writing about reading to engagement and motivation and more. One of the chapters was on reading with accuracy and it included 23 strategies, some of which are ones you’ll see that Jen and Dr. Cartwright recommend against. In 2021, she revised that chapter and made the revisions available for free to those who had purchased the first edition. The first edition is now out of print, though the chapter remains available online, and the newest edition, The Reading Strategies Book 2.0, (Amazon | Bookshop.org), includes an even more updated version.

A Summary of the Debate

If you’re coming into the world of reading instruction from the outside, chances are you may not be entirely clear on the nature of the disagreement. Even from within, the “sides” often talk about one another in polarizing language. So we started by carefully describing the various perspectives on the question of how we should be teaching people how to read.

“The way that reading is sometimes talked about in the media is very simplified,” Serravallo begins, “And unfortunately, when we simplify things, we get some very important things wrong.”

One common oversimplification she sees is reducing what’s known as the science of reading down to one word: phonics.

“The science of reading,” she says, “which I define as a vast interdisciplinary body of research explaining what happens when a reader is reading proficiently and how reading skill develops and how to teach reading, involves so much more than phonics instruction. And so to reduce it to just phonics is wrong.”

This reduction not only paints the science of reading advocates as if they don’t value any other strategies beyond phonics instruction, but it also positions those on the other side of the debate as being against phonics, which she believes is entirely inaccurate. “Honestly, I’m not sure anyone disagrees that we should teach phonics to beginning readers.” While there is disagreement about how much to do so, what approach to use, and so on, “most … understand the importance of including instruction in word reading and instruction in comprehension.”

If this is true, then why are educators put into these two opposing boxes? “I don’t think recent media reporting necessarily purposefully oversimplified reading instruction or reduced it to phonics alone,” Cartwright says. “What the reporting did was identify one particular set of pretty common instructional practices, for word reading in particular, that are not effective or aligned with the research.”

The practices she’s referring to are those that steer students away from sounding out an unfamiliar word, teaching them instead to rely on pictures, inferences, or adult support rather than decoding to figure out the word — or skip it altogether. When context is used to understand a word’s meaning, it’s perfectly sound. But using it in place of decoding the word is not.

“Using context to actually figure out what a word is, to decode it or to identify it, generally isn’t supported by research, but using context to figure out what a word means is,” Cartwright explains. “The only way to equip kids to actually decode words is to make sure that they’re aware of speech sounds, that the words we say are made up of individual sounds.”

Does that mean we should use both approaches together? According to research — and this is a crucial sticking point — the answer is no.”Some teaching practices for reading words, like looking at pictures, shouldn’t be there,” Cartwright says. “We don’t want our kindergartners and first-graders to think that that’s their go-to for reading words. We want the letters and sounds to be the go-to. We want them to have that knowledge systematically so they can use it. Because if we don’t equip them with it, they won’t be able to read the words they encounter when they have text without pictures.”

How Did We Get Here?

If non-decoding practices are counterproductive to teaching students to read words, how did they get so widespread? While the rise of some popular reading programs that promoted these practices certainly played a role, Serravallo and Cartwright believe there have been other significant contributing factors.

Inadequate Teacher Training

One likely source of the problem is a lack of consistent teacher training in phonics instruction. “Based on the National Reading Panel’s work in 2000,” Cartwright says, “if educators were lucky enough to have heard about it, either in teacher training or in professional development once they were in practice, they knew phonics instruction was necessary and that kids needed phonemic awareness, that awareness of sounds in speech for phonics instruction to work. But they didn’t really know how to do it effectively. So even if you’re a practicing teacher and you hear about this work, because you haven’t had the training, you don’t know how to implement this in your classrooms.”

This may have been overlooked for so long because many teachers are skilled readers themselves. “If we’ve gotten into education,” Cartwright says, “we probably like reading a little bit and we’re probably pretty good at it. And so we may not even be aware of how the words on the page leap into our heads. We just look at them and they’re there. And so we likely don’t even remember learning to decode or link the sounds in speech to print in a systematic way.”

The key word here is systematic. Many teachers may not realize how important systematic phonics instruction is because it wasn’t necessary for them. “I’ve heard a lot of stories of educators who didn’t understand the need for [systematic] phonics instruction until their own child had difficulty with reading,” Serravallo says, “and then it was a sort of wakeup call. They may have inferred from their own experiences learning to read or raising children that it was fine to teach phonics in a more incidental way — pointing out letter sounds in words as you’re reading with them versus having a systematic, sequential approach that many kids need.”

Memorization Masquerading as Reading

Another source of the problem might be found in the texts teachers have used for instruction and made available to students for independent reading. Even in schools where phonics instruction happens regularly, when it’s time for students to practice reading, the books available to students have not been aligned consistently with that instruction.

“(The books) might say something like, This is a giraffe, and there’s a picture of a giraffe on the page,” Serravallo says. “This is an elephant, and there’s a picture of an elephant. This is a tortoise, and there’s a picture of a tortoise. Giraffe and elephant and tortoise. If you’re a kindergartener, you cannot read those words by decoding. Literally the only way you could figure them out is to look at the pictures. So if these are the only materials in the classroom, you could see how teachers would think, ‘I’ve got to teach them to check the picture, because how else could they ever hope to be able to figure out that this word says elephant?'”

Fortunately, she says, this is changing. “We have a lot of companies now creating books that are more supportive of early developing phonics skills. These are sometimes referred to as decodable readers because the decoding ability matches what they’ve learned in phonics.”

While decodable readers have been around for generations, they were underused because of a lack of quality. “Most of them made little or no sense,” Serravallo says. “They didn’t sound like language. They’d say things like, Ed is on a bed that is red. On the red bed sat Ed. So folks who were trained to prioritize meaning making in their reading instruction understandably rejected these materials. They had a hard time understanding how they could possibly fit into their classroom.” Meanwhile, use of the early pattern books — like those elephant/giraffe books — grew in frequency.

So during those times when students should have been getting crucial practice in decoding words, they were reading books they mostly couldn’t decode. But here’s why this wasn’t caught as a problem: In a lot of cases, students looked and sounded like they were actually reading them. “When you use those early pattern books where there’s repeated words — This is a, this is a, this is a — with only one word changing that matches the picture, what you see is that kids very early seem fluent,” Serravallo explains. “They seem like they’re reading. So you’re like, You’re reading! They’re reading! They’re reading it smoothly, but they’re not, really. They’re not actually reading.”

This memorization-as-reading practice is taken a step further when students are encouraged to study high-frequency words — words like and, the, and of that are challenging to decode but appear often, even in beginning texts — without first working to decode them.

“You really want even a word like this to be decoded as much as possible or to point out irregular spellings in words so that kids are mapping the letters to the sounds,” Serravallo explains. “I think that for a time, people thought, oh, if they just see the word this over and over again, they remember it. But what we know from research is that kids need to orthographically map the word. They have to match the sound and the spelling. So we want them to actually labor a little bit through that phase of decoding. When you replace the This is a, this is a pattern kind of text with a decodable text, the reading is slower; it looks like there’s more of a struggle at first.”

And on a neuroscience level, Cartwright says, that struggle is exactly what we want. “That laboring, that work of connecting letters and sounds to figure out what a word is, that’s actually building the connections they need in their reading network in their brain.”

This approach doesn’t mean that students will be sounding out words forever. “Words become automatic or become sight words through that process of orthographic mapping,” Cartwright explains. “So if I’m a child who has read ‘dog, d- o- g, dog, oh!’ and then I do that a few times and it’s effortful, but I’ve mapped those sounds onto those letters and connected it to that furry four-legged barking thing over a number of exposures, then I start to see it and that happens automatically.”

Misconceptions about Reading Instruction

Much of the debate over how we teach children to read is based on some common misconceptions.

Misconception 1: Learning to Read is Simple

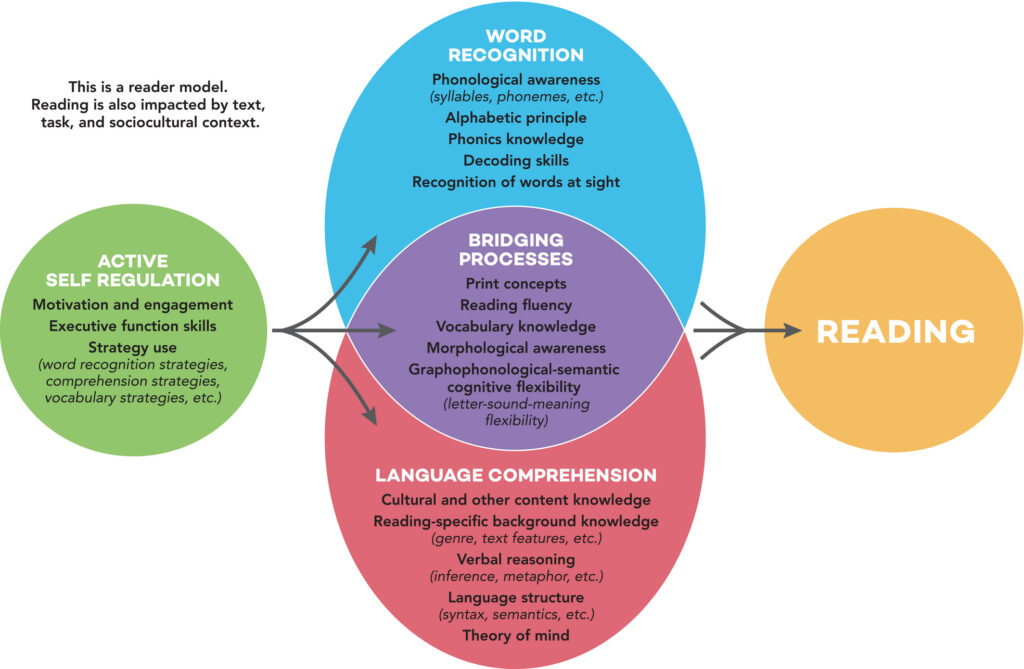

The Simple View of Reading framework, a widely known conceptualization of reading developed by Gough and Tunmer in 1986, posits that reading is the product of word recognition and language comprehension. While both Serravallo and Cartwright believe these two areas are critically important, the model misses two important facts about reading that have been uncovered by research since the model was introduced:

- Word reading and language comprehension aren’t separate. “They’re often presented as two separate buckets of skills that we deploy separately,” Cartwright explains. But in fact, “They overlap. And they need to be coordinated while we read. In study after study, the overlap’s contribution to reading comprehension is actually bigger than the individual separate contributions of word reading and language comprehension alone.” To bring both skills together, readers recruit what Cartwright calls bridging processes.

- Self-regulation plays a major role in reading. “Research shows us that good readers actually recruit their active self-regulation skills,” Cartwright says, “things like executive function skills and motivation and strategic knowledge such as knowing how to tackle a multi-syllabic word to decode it or knowing how to supply your own knowledge and combine it with text elements to make an inference from text. These kinds of self-regulation processes really enable readers to actively manage their word reading, to actively manage their language comprehension, and then to coordinate those processes while reading.”

Along with her colleague, Dr. Nell Duke, Cartwright has developed a newer framework, the Active View of Reading model, that adds these two components —into reading instruction.

“With that view,” Cartwright says, “we’re hoping to help educators see reading in a more complex way and target particular things in instruction that can move that needle forward on reading achievement for their students.”

Misconception 2: The Science of Reading is Fixed and Clear-Cut

When educators refer to the Science of Reading, they may not always mean the exact same thing. That’s because the Science of Reading continues to evolve as more contributions are made from many different disciplines. Cartwright lists just a few of these: “We’ve got people in cognitive science. There’s human development and linguistics and neuroscience and psychology and special education and speech language pathology. I could go on and on.”

With so much coming from so many different directions, that science doesn’t make it to our classrooms uniformly. “Sometimes the science is very siloed, and the classroom practice is siloed,” Serravallo says. “We need more science to classroom practice collaboration.”

Another limitation of the current body of research is that it has historically ignored large groups of people. “There’s a tendency to privilege quantitative experimental studies,” Serravallo says, “which leaves out valuable findings from qualitative studies, and as Dr. Gholdy Muhammad said, excludes the experiences of entire groups of people. There also needs to be an increased attention paid to how language, like multi-lingual learners or culture, comes into play when discussing developing literacies.”

With all of this in mind, teachers should build their approach to reading instruction from a variety of sources, including their own students. “It’s super important for your evidence-based instruction not just to be based on research evidence but to also be based on your own students’ data and progress monitoring to make sure that they’re progressing in ways you had hoped and expected,” Cartwright says.

Serravallo agrees. “Teachers need a variety of tools and approaches to support different readers and be able to kind of turn on a dime and say, ‘I know that this study found that this worked. This particular kid is not responding. Let me try something different.’”

Misconception 3: We Need to Choose Between Teaching Strategies and Building Knowledge

“There’s been a recent shift to a new debate which is around the idea of skills and strategies instruction versus knowledge-building,” Serravallo explains. “But this is a false dichotomy. Like many things with reading instruction, the answer is ‘both and,’ not ‘either or.’ There are decades of research detailing the value that teaching strategies has to all areas of reading, (but) we don’t do that in a vacuum. We do that with real texts with real knowledge. Children learn to use strategies for reading while reading, and the goal is never that these strategies are in and of themselves the goal.”

“Strategies without knowledge won’t help students understand text,” Cartwright adds. “Knowledge without strategies, again, won’t help students understand text. Skilled readers do both.”

Moving Forward, What Should Teachers and School Leaders Do?

With all of these complexities to consider, teachers might have trouble figuring out the best course of action. Here are some general pieces of advice:

Listen to each other.

“Teachers need to learn from researchers,” Serravallo says. “Researchers need to learn from teachers. Policymakers need to listen to experts, and overall we need to be humble, and we need to realize that no one person has all of the answers.”

Be flexible and open to change.

“The answers are likely to continue to evolve as more research happens,” Serravallo says. “We need to pay attention to all areas of research, not cherry-pick just some studies or some fields or some aspects of reading or promote the idea that there’s one single approach that’s perfect for all children. While it’s true that there are statistically significant findings that show generally what most kids need, kids are unique.”

Beware of one-size-fits-all claims.

“The idea that any curriculum will be what every child needs as written is a false promise,” Serravallo warns. “There are many districts that are rolling out new boxed curriculum and are saying they no longer have funds or time to invest in professional learning for teachers, so that their sole focus is going to be on implementing these new materials. That is not going to go how they hope it’s going to go.”

Cartwright agrees. “We’ve got to know what our students can do when they get to us, and we’ve got to know what they cannot do so that we can differentiate to meet them where they are and then move them forward.”

Give teachers the time they need to teach their students well.

Teachers can’t do much with the above advice if they don’t have time built into their workday to get it done. “This model of having somebody from the curriculum product come in for a day and ‘train teachers’ on how to use this curriculum product, that is not going to get them to have these collaborative conversations, grapple with the research, look at their students’ responses to different instruction and make adjustments and try new things,” Serravallo says. “It really speaks to the need for ongoing professional learning that allows teachers to work together, to collaborate, to go into classrooms together, to try things in the company of other educators, and to reflect.”

Worth the Effort

After listening to these two literacy experts, I’m no longer intimidated by the conversation about reading instruction. I no longer think it’s too complicated to touch. It’s complicated, yes, but not impossible to figure out. The complexities are actually pretty fascinating, and if we make time and space for them, we’ll literally change lives.

“Literacy really lays the foundation for life success,” Cartwright says at the end of our interview. “Reading ability predicts academic outcomes. Reading ability predicts career advancement and where you’re going to end up in your career. Low literacy literally sets people on a trajectory of disadvantage because it predicts poor health, not just physical health but also mental health. People, both children and adults, with low literacy skills are significantly more likely to suffer from anxiety or depression. Low literacy limits the ability to work. You can’t actually do most jobs if you can’t read, and you can’t even fill out a job application if you can’t read. So flipped around, we can think about literacy as being the key to opportunity, and we as educators need to make sure that we’re equitably equipping our students to meet those opportunities with the best science-based reading instruction we can offer.”

You can learn more from Jen Serravallo at jenniferserravallo.com, where you’ll find articles, links to her books, and her podcast, where she has in-depth conversations with educators about literacy best practices. Dr. Kelly Cartwright can be found on Twitter at @KellyBCartwrig1. Be sure to check out her book, Executive Skills and Reading Comprehension: A Guide for Educators (Amazon | Bookshop.org).

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Thanks for this post about reading strategies. It’s informative for me as someone not familiar with this topic. I’m curious if you could provide further resources to follow up on this important part:

“Does that mean we should use both approaches together? According to research — and this is a crucial sticking point — the answer is no.”

Can you share links to a sample of this research?

Thank you.

I would check out Linnea Ehri’s writing on this topic. Here’s an open access piece about orthographic mapping and the importance of teaching children grapheme-phoneme correspondence to decode words: https://registrar.ecu.edu/wp-content/pv-uploads/sites/257/2019/07/ehri.pdf

Excellent discussion in tone and content. I am disappointed that Ms. Sarravallo’s pointed points made pointedly at 1:06:00-1:09:00 are not highlighted, or even covered, in the “transcript” summary. Ohio’s SOR (stands for SORry) plan has the anti-science 3rd grade literacy test mandate, and $64 million for curricula, $86 million for PD [“having somebody from the curriculum product come in for a day”], and $12 million for literacy coaches. In other words $150,000,000 to go to cronies in publishing and to not-in-classrooms, self-proclaimed product experts and for caterers’ bad coffee, warm OJ and stale danish. And a tiny bit to folks in classrooms. Let’s end more positively. I feel in debt to the 3 knowledgeable, insightful and wise women both calmly revealing the ingredients and excitedly stirring the pot.

Hi, Paul. I just wanted to let you know that the interview transcript, which you can find here, is different from the interview summary provided in this blog post. The transcript covers the complete interview, including the portion you’re looking for. Because the conversation was so rich, it was very difficult for Jenn to condense the interview into a summary of key points for a single blog post, but she did her best! I hope this is helpful.

Thanks for writing about the Science of Reading. I have long followed education policy over the last almost two decades as a hobby of sorts, but this SOR kind of caught me by surprise (or maybe I wasn’t paying attention). I’m concerned that the public / policy makers will think that magically reading scores are going to dramatically improve overnight. I also don’t like some of the rhetoric, at least on social media, of folks being disparaging to educators, education professors, and the like. However, I do agree that it’s always good to self reflect, improve, and be flexible, so I hope that’s what we see.

This article had a lot of support for being fair in explaining the entire SOR for the public:

https://www.vox.com/23815311/science-of-reading-movement-literacy-learning-loss

I read all your blogs and appreciate them. I’m a university professor and I work with teachers. I listened to the entire interview on the science of reading hoping for a critical lens and was disappointed there was no unpacking of the serious critiques of yet another neoliberal education reform that will take money and time away from what schools actually need. Here are some good pieces that attend to intellect and criticality (as Gholdy Muhammad pushes educators to do):

https://ncte.org/blog/2020/10/critical-story-science-reading-narrow-plotline-putting-children-schools-risk/

https://radicalscholarship.com/2023/07/22/neoliberal-education-reform-science-of-reading-edition/

Rhina, thank you for sharing these resources. The debate over reading instruction is undoubtedly a complex issue with many, many layers. Jenn’s intent with this particular post was to focus on practical, actionable strategies that teachers can use to directly address reading instruction in their classrooms. However, the sociopolitical context is important, and we appreciate you linking those articles so that others can read them, as well.

Hi Rhina – These are important points and considerations for sure! As Margaret from Jenn’s team mentioned, Jenn was hoping to keep this episode focused on clarifying what the debates are about and what teachers should do. So while the majority of the episode focused on what we hope are practical considerations–and some real shifts that are likely to benefit students–I do want to draw your attention to some of my comments that I think align to your critique. I discussed, for example, spending on new curriculum and having nothing left to support teachers with professional learning, the legislative attention focused on how reading is taught while children starve and don’t have basic medical needs met, and my very real concern that this legislation often comes with retention policies that are demonstrated by science to be harmful to children. I hope what I communicated in this interview is that while I am and always have been supportive of learning from research, it’s critical that we examine all the research, and that we don’t look for any one silver bullet (and put all our eggs–and money–in that basket). Thanks for commenting to give me the opportunity to clarify. I encourage you and others to check out my podcast, To the Classroom (www.jenniferserravallo.com/podcast), where I explore many of this topics and more. Again, like Margaret said, it’s a lot to squeeze into an hour, but the full complexity of these issues are critically important for us to consider, weigh, and respond to. We mustn’t oversimplify.