Listen to the interview with Melanie Meehan (transcript):

Sponsored by EVERFI and Today by Studyo

This page contains Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

Over the years, we’ve covered a lot of different ways to differentiate and personalize instruction, methods for giving each student what they need when they need it, rather than planning the exact same learning experiences for everyone, every day. (Click here to see all of our posts that connect to differentiation in some way.) The good news is that there are so many ways to differentiate — here we’ll focus on another strategy that we’re calling seminars.

I say “we’re calling it that” because I assume you’re already familiar with the word seminar — a short-term gathering of people for the purpose of learning about a given topic. Typically, adults attend seminars. University students attend seminars. What we’re talking about today is offering a version of that concept to students within your own classroom. These seminars are mini-lessons given during class time, but the key is that most of the time they are optional — students only sign up to attend if they have an interest in or need to learn more about the topic. And yes, they could just be called mini-lessons — in fact, I heard about this same concept years ago from the high school teachers at the Apollo School — but something special is added when you call them seminars.

That’s what Melanie Meehan calls them. Meehan is a Connecticut-based elementary writing and social studies coordinator who has written three books about teaching writing and contributes to the collaborative blog Two Writing Teachers. She appeared on episode 192 of the podcast, where we talked about backward chaining, another differentiation strategy. While working on that piece, she also mentioned the seminar strategy, and I liked it so much I thought we should give it its own separate space.

In the podcast episode above, Meehan talked with me about the logistics of how she sets seminars up in her classroom and what an effective tool they are, not only for differentiation, but also for building student agency. And just like with backward chaining, seminars can be used in any subject area and any grade level.

What do seminars look like in a K-12 classroom?

“Basically, seminars are small group instruction,” Meehan says, “and that is, as far as I’m concerned, the sweet spot of differentiation.” She acknowledges that seminar is a deliberately ‘fancy’ word, but “it’s a word that kids love.”

The seminars are 7 to 10 minutes long, with each seminar covering a small, focused topic. They are offered during times when students are working independently on other tasks. During a typical class period, Meehan usually offers one or two seminars.

When she first introduces the concept of seminars to students, she talks about her own daughters attending seminars in college: “It was the special classes where they got to really work on what they were interested in. So I’ll bring them up as seminars in terms of what are you really interested in learning about? And it just generates some excitement and some joy around the whole process.”

Nuts and bolts: What are the logistics?

Choosing the Topics

Seminars can be offered in any subject area; because she teaches writing, Meehan’s seminars are all geared toward that. “It can be any of the learning targets that align with the standards that the unit’s going after,” she explains. “So that could be developing sections for my writing, it can be making sure that I have enough information in a given section. It can be making sure my reason’s clear. Depending on what genre they’re working on, those seminars can be content-specific. But they can also be writing behavioral. They can be, I’m having a hard time getting to work. I’m having a hard time staying on task. So sometimes I’ll put those up too.”

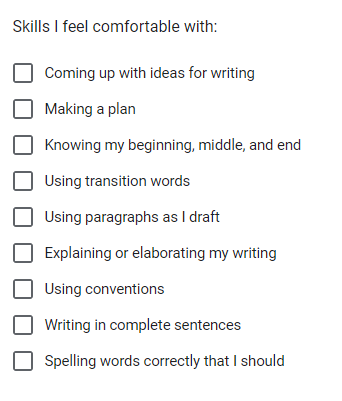

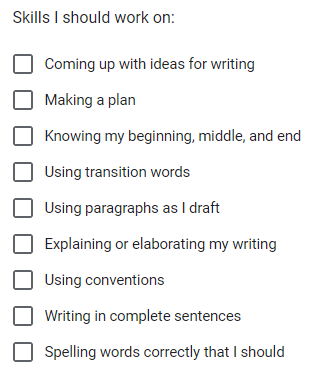

Topics can come from Meehan’s observations of students at work, noticing areas of struggle. They can also come from student surveys. Meehan has a Google Form (click here to make a copy) that asks students to evaluate themselves with these questions:

“Once I have that information,” Meehan says, “I can establish seminars based on that. If I get four kids who have checked that they need some work on including small stories into their argument pieces, I’ve got a seminar going.”

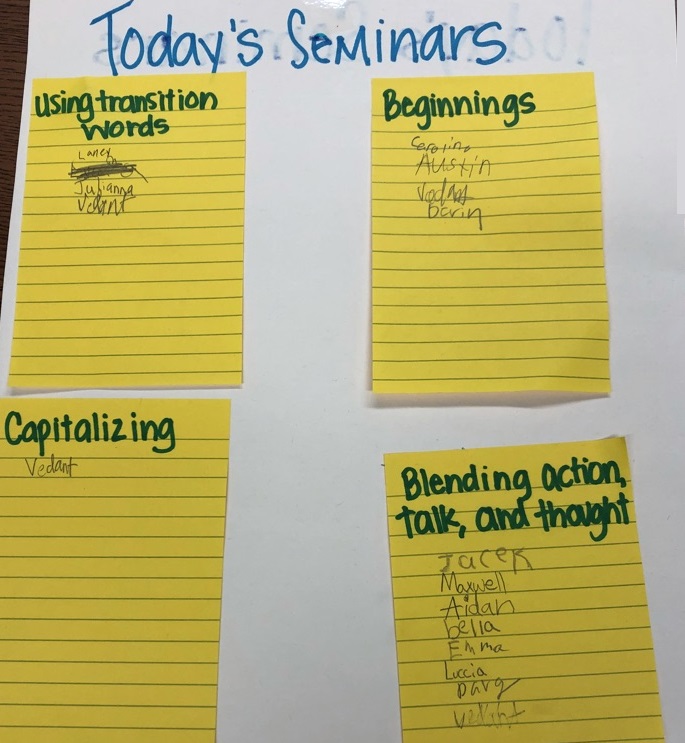

Sign Ups

Meehan has students sign up on a sheet of chart paper with lined sticky notes indicating the seminars being offered that day. “So I can just pull that sticky note right off of the chart, and be like, oh, okay. You four needed to work on ways to help your introductions. Great. Seminar’s going on about hooking introductions. I’ve got Jenn, Melanie, Garth, and Julia, you four come on up. I’m giving that right now.”

Ideally, seminars will only be given to groups of four to five students. If more than five sign up for a seminar, Meehan will offer two separate sessions. If a large number of students show interest in a topic, that becomes a whole-class lesson.

How do these lessons fit into class time? Meehan describes a typical 45-60-minute class period: “I’m envisioning a 7 to 10 short, what we would call a mini lesson. So a quick, here’s your learnings for the day. You don’t necessarily have to do it today because you might be in a different place in your writing process, but probably at some point in this unit, you are going to need this teaching point. And, you know, off you go, and you’re working on your independent pieces. So during that independent time, and in my head, there are two 20-minute solid blocks of independent writing time. So you’ve got your 7- to 10-minute full group lesson that everybody’s listening to, you’ve got your 20 minutes of independent writing time, during which time you have the opportunity to teach kids as small groups or teach kids individually. I like to challenge the teachers that I work with to think about having in those 20 minutes one small group and one conference, at least.

“So if you can fit those in in those 20 minutes, then you’re doing a good job being efficient, because after that 20 minutes, you’ll do a quick interruption. You might highlight something that you saw. You might have an additional teaching point, you might ask somebody to share what they’re proud of. That’s the two-, three-minute interruption, which sometimes kids need, right? Great, everybody. Back to work. You got another 20 minutes, and teacher, you’ve got another opportunity for another seminar and another meeting with the kids.”

Are seminars always self-selected?

Meehan’s long-term goal is to build student agency, with students understanding their own needs and taking steps to meet them. Seminars are an important part of making that happen. “Ultimately the goal of learning is transfer,” she says. “It’s owning your learning and being a learner out in the world without a teacher at your side. So I love having kids sign up for their own seminars.”

With that said, Meehan also occasionally assigns seminars to students. If a seminar is being held and she knows a student needs to work on that particular skill, she’ll either gently encourage them to attend or simply tell them they really need that seminar. And if, during a writer’s workshop, she notices four or five students who appear to be stuck or off-task? “You’ve got a seminar. Like, hey, friend, have I got a seminar for you. This one’s going to be mandated.”

Sometimes student choices don’t always align with what Meehan thinks they need, like when a student chooses a seminar on a skill they have already mastered. But in those cases, she usually won’t interfere. “I can move them along quickly through the choice that they’ve made and honor that choice,” she says. “And then they’re much more pliable toward my recommendation for the next one.”

Leveling Up: Student- Run Seminars

Once students have gotten used to attending seminars run by the teacher, you can start to move toward having students give the seminars themselves. When Meehan notices that a student really understands a topic, she’ll instruct them to listen to her give a seminar as if they’ll have to teach it themselves.

“I’ll be like, you’re going to be the one who listens and then turns it around because we’ve got so many other kids who need it,” she says. “So you’re going to become my teaching partner, and at the end of this, you’re going to go off and teach it to another group, and I’ll teach it to the other group.”

By taking this approach, Meehan not only becomes more efficient at managing demands on her time, she also builds more confidence and agency in her students.

“I think that we run past the power of the abilities of some of the kids in the room,” Meehan says. “Kids are sometimes really effective teachers to each other.” So if she notices that a student is starting to master a skill, she might say something like, “You’ve used transition words brilliantly in your piece. Could you run a seminar on that for your friends?”

Having students teach each other also pushes them to a new level of mastery. “A kid might have a specialty or a strength that they want to develop, and that also forces them to kind of prepare for it and make sure that they’re extra good.”

Seminars in Any Class

Although this idea is being presented here in a writing class, which is built on a workshop model, seminars could be offered in any subject area. Even if you are teaching a content-heavy subject, as long as you build in some time for students to work independently, you’ll have an opportunity to offer seminars on the unique set of skills needed for success in your subject.

LEARN MORE

You can find more from Meehan on her website, melaniemeehan.com. The seminar approach appears along with lots of other fantastic strategies in her 2022 book, Answers to Your Biggest Questions About Teaching Elementary Writing.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Well done. Thanks for doing this.

My name is Jason Reagin and I am the MS Curriculum Coach and IB MYP Coordinator at the Western Academy of Beijing in China. I was intrigued by this podcast episode and blog post. At WAB we are implementing many things that encourage choice both inside and outside of the classroom… For example, our middle and high schools are on a ‘nine-day’ cycle. We have a regular eight-day rotation and then on Day 9 we do not have classes, but we have ‘workshops’ for students run by teachers and older students. These sessions are a balance between academic and enrichment topics. We are still developing our overall protocols, but the initiative is really fun for the whole community. Obviously, not all schools can do this (in fact, very few can) but by hearing about it educators immediately start to ask ‘how can I do that?’ Here is a link to a short podcast about this at our school!

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/how-day-9-enhances-individual-learning/id1532277305?i=1000583354048

Thanks for sharing this, Jason!

This article was SO GOOD – I’m going to reference it in an upcoming district inclusion workshop. I can totally envision how to transfer her suggestions to classroom practice. I love the focus on student agency balanced with the practical acknowledgement that sometimes we will directly recommend a student ‘attends’ a seminar. I’m still wrestling with how to do long blocks of independent learning consistently in content-heavy courses like science.

Sarah, Jenn will be glad to hear that you found the article to be helpful! For one way to structure independent learning in content-heavy courses, I’d recommend checking out this guest post by Kareem Farah on self-paced classrooms. I hope this helps!