Listen to my interview with Joe Hirsch (transcript):

Sponsored by Kiddom and Pear Deck

This page contains Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

As teachers, we pretty much give feedback all day long. We tell students how they can improve on assignments, we praise them for things they’re doing well, we correct their incorrect responses, and we redirect them when they behave in ways that aren’t helpful to learning.

And that’s just the students. We also give feedback to our colleagues, although in most cases, these exchanges don’t happen as often or as freely as they probably should. We receive plenty of feedback as well, from our students, their parents, our administrators, and our peers. And we encourage our students to give feedback to each other, albeit with pretty uneven results. Really, the experience of school could be described as one long feedback session, where every day, people show up with the goal of improving, while other people tell them how to do it.

And it doesn’t always go well. As we give and receive feedback, people get defensive. Feelings get hurt. Too often, the improvements we’re going for don’t happen, because the feedback isn’t given in a way that the receiver can embrace.

It turns out there’s a different way to give feedback that works a lot better, a way of flipping its focus from the past to the future. It’s a concept called “feedforward,” which was originally developed by a management expert named Marshall Goldsmith. As far as I can tell, not a lot of educators are familiar with the practice of feedforward, and I really think if we learned how to do it and started using it more consistently, it could make a huge difference in how our students grow and how we grow as professionals.

In this week’s podcast, I interview Joe Hirsch, author of The Feedback Fix: Dump the Past, Embrace the Future, and Lead the Way to Change. In the book, Joe digs deep into the practice of feedforward and shows us how and why it works. You can listen to our full conversation in the player above, read the full transcript, or stay right here—I’ll give you a quick overview.

What’s Wrong with the Way We Give Feedback?

When we give feedback to our students, or when our co-workers or administrators give feedback to us, the focus is on the past. “People can’t control what they can’t change, and we can’t change the past,” says Hirsch. “And that happens to be the focus of most of the feedback that we give or receive.”

More specifically, backward-looking feedback doesn’t often get good results for three reasons:

- It shuts down our mental dashboards. “When we get negative feedback about something that we can’t change or control,” Hirsch says, “our brains flood with stress-inducing hormones, cortisol, that trigger our threat awareness and put us on the defensive. The parts that are responsible for executive function, for creativity, the parts that allow us to sort of set our agendas and make rational decisions, essentially we are in a state of mental paralysis.”

- It focuses primarily on ratings, not on development. Most of feedback’s time and energy is spent on looking back and rating (or grading) performance that’s already over, rather than focusing on what can be done from now on. “When feedback consists of an impersonal set of performance standards, we’re overlooking the essential goal of feedback, and that’s to create positive and lasting improvement.”

- It reinforces negative behaviors. “When we hear about flaws that we can’t fix anymore—because they’re in a past that we can’t change—it creates a feeling of learned helplessness, the feeling that we are unable to do anything about our future. Instead of committing ourselves to improvement, which is what we would hope would happen, we hold onto this debilitating view of who we are instead of focusing on who we are becoming.”

What is Feedforward?

When we give feedforward, instead of rating and judging a person’s performance in the past, we focus on their development in the future.

Suppose my student is writing an essay. Instead of waiting until she is finished, then marking up all the errors and giving it a grade, I would read parts of the essay while she is writing it, point out things I’m noticing, and ask her questions to get her thinking about how she might improve it.

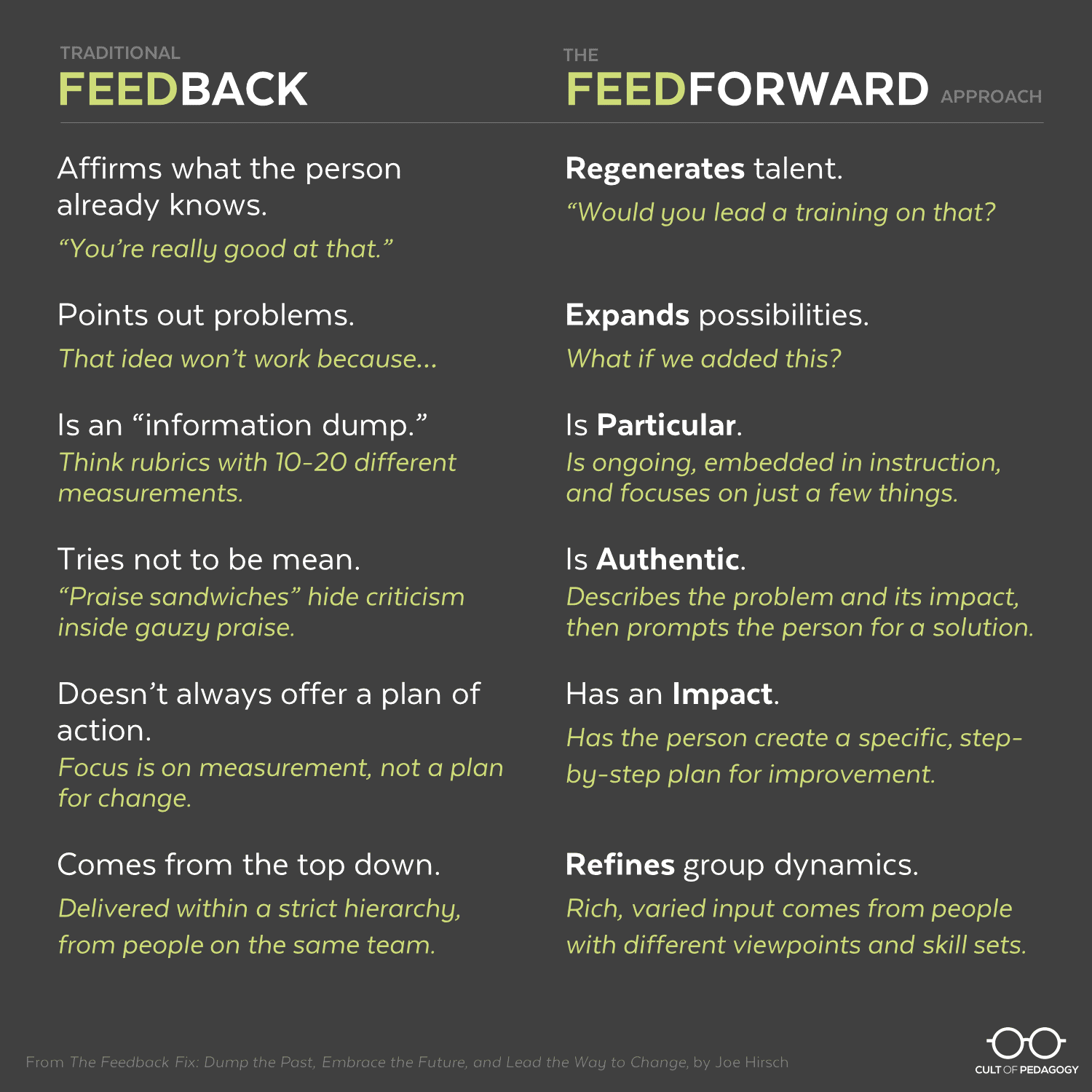

In his book, Hirsch takes this broad concept of feedforward and defines six components of it, six specific characteristics of feedforward that make it so effective. He refers to these by the acronym REPAIR (regenerates, expands, particular, authentic, impact, refines).

So let’s take a look at each of these. If you want to implement feedforward well, it should have these attributes:

It REGENERATES talent.

The most effective kind of feedforward helps people see opportunities for growth—ways they could take on new opportunities and roles. “At the simplest level,” Hirsch writes in his book, “it leads to the unmistakable feeling that we’re moving forward in our professional and personal lives. Getting positive feedback about our performance may feel good, but it doesn’t break new ground. It merely confirms what we already know about ourselves and our talents, essentially holding our growth in check. But when feedback gets us thinking about how to spread that talent to others, it has a multiplying effect.”

So when we notice that a student is developing a strength or an interest in an area, instead of just pointing that out, we might give the student an opportunity to enter their work in some kind of competition, publish it in some way, or share it with others in a presentation, rather than simply keeping it to themselves. This helps students see themselves in a new light and gets them thinking about ways they could grow.

It EXPANDS possibilities.

Effective feedback starts with what is and helps add to it, expanding what’s possible, rather than simply pointing out problems. In his book, Hirsch describes a concept used by Pixar studios called “plussing.” When Pixar’s creators get together to review a day’s work, they are expected to give each other feedback to improve the work. What makes these sessions so effective is one important rule: Participants can’t point out a problem without proposing an alternative, saying “What if?” to a problem.

This concept of “plussing” could work wonders in staff or committee meetings: When we are discussing possible solutions to an issue, rather than shooting down ideas that might not work, we could add to them by making small tweaks. “That’s an interesting idea. What if we made this small change and tried that?” This technique would also work beautifully with project-based learning tasks, when students may need to come up with several ideas for solving a problem before arriving at the best solution.

It is PARTICULAR.

Far too often, feedback is given in an “information dump,” with lots of criteria being measured and reported on at the same time. This can be a pretty ineffective way to help people grow. “There’s a limit to how much we can absorb and operationalize in any given time,” Hirsch says. “Feedforward is really about picking your battlegrounds strategically and selectively.” He advises us to make feedback an ongoing process that is embedded in the day-to-day work, and to only focus on a few things at a time.

So rather than wait until an assignment is done to point out all the ways a student can improve, find ways to give them specific pointers while they work, and only one thing at a time, so students can process and act on it right away.

It is AUTHENTIC.

No one particularly likes giving criticism. “We see problems, we see pitfalls in other people, and we know it’s a problem,” Hirsch says, “but we don’t want to be mean, right? We don’t want to crush them. So the tendency is to either avoid giving feedback altogether or to disguise it as a praise sandwich, where we basically slip one piece of criticism in between two very, very surface level gauzy praises.”

The problem with that approach, Hirsch explains, is what’s called the recency effect: People remember most the thing they heard last. So when you tack on some praise after delivering constructive feedback, the person doesn’t really absorb the critical part as well as they would if you’d just given it to them more directly.

Hirsch recommends a more direct approach: Describe what’s happening, explain why it’s a problem, then prompt the person for a solution. “When delivered this way,” Hirsch explains, “it puts people at ease, it takes them off the defensive. It is clear, it is concise, it’s locating the problem, it’s looking for solutions together. People don’t want a praise sandwich. People want the truth.”

This approach could work with academic situations or classroom management problems: If you’re dealing with a student who is disrupting class, describe the behavior you’re seeing, explain why it’s a problem, then ask the student for ideas on how to solve it. It sounds really simple, but if what you’re doing right now isn’t giving you the results you want, it’s worth a try.

It has IMPACT.

One of the reasons people don’t make progress after receiving feedback is that they don’t necessarily know what to do with it. “If you want feedback to make an impact,” Hirsch notes, “you have to put it in terms that people can operationalize.” In his book, he cites studies showing that regular feedback doesn’t typically result in a transfer of new skills or habits, but when that feedback is combined with coaching, the transfer skyrockets to 95 percent.

So if a student regularly forgets to bring materials to class, rather than simply telling him to change, help him make a specific plan for improvement. Ideally, that plan should have lots of small steps to make it achievable, and the student should take the lead in developing that plan.

It REFINES group dynamics.

“Feedback is a team sport,” Hirsch says. “It is not just something that happens one to one. It happens in groups and across and within organizations. And when we dump that command and control nature of traditional feedback, we make room for something much more collaborative and shared.”

So rather than give feedback in a top-down, hierarchical model, open up more pathways for people to get feedback from their peers, even those whose jobs might on the surface have little in common with our own. In his book, Hirsch borrows a term from management circles known as “creative abrasion,” which is what happens when people with opposing views work on the same task together. Although it can result in more conflict, the contributions from different points of view usually produce a higher-quality product in the end.

This idea can play out in a lot of educational settings: Instead of just having our department head observe our teaching, why not get feedback from someone who teaches a completely different subject? When students go to the same peers for feedback on their work, have them seek out the opinion of someone new, or consider getting the input of a group of students from a different class or grade level entirely.

There’s nothing simple or straightforward about telling people how to improve. So it’s no surprise that we’re still figuring it out and finding new ways to refine it. If the feedback you’re giving to your students, your coworkers, and even the people at home isn’t having quite the effect you intend, try shifting to a feedforward approach. Doing so can help us, as Hirsch says, stop seeing ourselves just as who we are, but who we are becoming. ♦

Learn more about Joe Hirsch on his website or visit his LinkedIn page. Teachers who read The Feedback Fix should also grab this free Discussion Guide for Teachers to help apply the book’s principles to your own work.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

You make a great case for good practice here. But I see it as just another name for formative feedback, which isn’t a new concept. What do you see as the difference, or how does feedforward include or build on formative feedback?

Really great question! Wish someone would have answered it in the context of this post/podcast-

Hi Jennifer,

As a school principal, I find myself tuning in more and more to your site because your focus on relevant topics is terrific. What struck me most about this blog post was “Hirsch recommends a more direct approach: Describe what’s happening, explain why it’s a problem, then prompt the person for a solution.” I like the focus on a solution based culture where teachers and administrators don’t just “dump” the feedback and leave but stay and collaborate on solutions. This willingness to spend the time to discuss and brainstorm can move the culture to dramatic improvement.

I like the comment “Really, the experience of school could be described as one long feedback session, where every day, people show up with the goal of improving,” as it gets to the heart of the matter. Time is the ever-present obstacle, but the possibility of adjusting how we are spending it makes me think.

Great Post.

Greg Adams

Elementary Principal

This fits in quite well with several approaches that are popular in the UK – Assessment for Learning (rather than assessment for grading) or DIRT (dedicated improvement and reflection time) – because they all focus on giving students information to move forward. DIRT in particular gives students an immediate opportunity to improve their work (so in a way it did get marked before it was finished). I also have students go back through their assessed work to find their targets so they start with feedback as well.

I am most interested in the feedforward approach as a way of dealing with colleagues – I can see that this would be really useful to have in mind when managing staff as well as during staff meetings!

Jennifer,

First off, thank you for your blog and podcast! I have benefitted much as a newer (in my second year) teacher from the quality content that you consistently produce.

While listening to this podcast last night and this morning on the way to work, I thought of my own feedback habits and was challenged. I was also reminded of Reader’s Workshop and my conferring with students. Rather than going over a finished product, I know I should be focusing on the writing in progress. It’s challenging for sure, but I owe it to all 29 of my fourth-graders. Starting with our informational writing unit this week, I will focus on one aspect of a student’s writing at a time, using the strategies outlined in this episode.

Again, thank you!

Respectfully submitted,

Shawn

Hey, Shawn! I work with CoP — we’re so glad to hear how much you enjoy the site. If you get a chance, let us know how it’s going as you try out some strategies from this episode!

Hi Jen! I’ve been using a variation of this for a couple of years. I allow students to revise their work after it’s due–especially writing assignments. (In the real world, authors submit and resubmit to their editors until it’s ready for publication, and I want to replicate that. Any assignment like a test where the writing is done once and turned in needs to be treated as a first draft, which I think many teachers forget.)

We use Google Docs which let me easily post comments and paste in rubrics. Many students receive grades they don’t like the first time around, because I tailor the rubrics to look for specific things that we’re working on in class. A typical first-time-around grade will be something like 20%.

My students will resubmit revised writing up to 6 times (so far). I scaffold my feedback. The first time is just the rubric so that the student can reread their work to figure out what needs “fixing.” Each time after, I get more specific. I’ll highlight a whole paragraph and comment that something in this paragraph needs some work. Next, I might identify what in the paragraph needs to be looked at (in-text citations, run-on sentences, etc.). THEN I might include a link to a Web page or short YouTube video that explains the concept (like hanging indent in the Works Cited page).

I did a guest post on Kristy Louden’s blog about this: https://www.loudenclearblog.com/2017/08/25/using-gafe-delay-grade-guest-post-chris-miller/. There’s also a sample doc I use with pre-made comments with links that I use to copy and paste into my comments.

I find that students learn more meaningfully with the scaffold feedback rather than having me identify each little problem so that they can just fix it without any searching.

Thanks so much for sharing this process, Chris. I am a big believer in multiple submissions for writing pieces. I’m also with you on giving different kinds and levels of feedback at every stage. It’s so easy to get overwhelmed by too much feedback, so I really like your scaffolded approac.

Quite a few of the professors I support resist rewrites/revisions because of the time commitment. One of the techniques I suggest to them is to give students specific improvement goals in the form of “next time” statements, and to retroactively raise students’ grades on prior assignments if the students follow through on the “next time” guidance on subsequent assignments. For example, let’s imagine that a psychology professor has assigned two papers, and proper formatting of citations in APA style is one dimension of the grade. Imagine that a student neglected the style guide on paper #1, or didn’t really understand the style guide, or for some other reason turned in citations that don’t follow APA style. The professor could coach the student on APA style (in the “next time, be sure to do this” register), and then if the student does improve their use of APA style on the paper #2, the professor could raise the student’s grade on the APA style dimension of paper #1 as well (by the full amount or some proportion thereof). This provides the student with the same forward-looking learning benefit as revising the citations in paper #1, and spares both the student and the professor the additional workload of looking backward at paper #1. Of course, scaffolding in citation practice before paper #1 would be even better, but this is my own version of “feedforward” that some of my colleagues are willing to adopt when they’re not willing to do the extra work of regrading revised papers.

Hey Christopher, thanks for sharing your insights. “Next time” statements seem like an effective take on the feedforward idea.

Good evening!

Thank you for posting this; I ran it across it from a Twitter retweet and seeing as this is our district priority right now, I felt that this was a really good thing for me to put into my learning bank.

What I see with the list that he has identified up above with traditional feedback and feedforward approach run together almost simultaneously. For example, “You’re really great at XYZ, do you think you could help me with breaking down the steps you took to get to that point so I can help Teacher A?” I think you are giving them feedback and allowing them to feedforward.

It was great to listen to and hear and I am glad that I had the opportunity to come across this.

Thanks!

As an Instructional Coach, the FeedForward concept really promotes a growth mindset when working with staff and students. The idea of “plussing” would be beneficial when coaching a colleague. Through this concept, a results based environment would begin to cultivate solutions between a coach and a teacher where all are working together to find solutions and feel validated through the FeedForward process.

How might Joe respond to a reading of the Israeli parole board study that says it’s not at talk about decision fatigue, but it’s instead about hunger (as the study authors proposed and backed up)?

Hi Vic,

Thanks for your comment. The two appear to be co-dependent – as a result of their physical strain (brought on, in part, by hunger), the judges were prone to fatigue.

I’ve recently started following CoP and am enjoying the different articles and how they pertain to my day to day teaching.

I chose this article because it ties in well with my own, learner-centered pedagogy and I wanted to see what you had to say on the topic. I believe that by giving individualized feed forward, learners can work to their highest challenge level. I love the term “regenerates talent” because I think that formative feedback helps the learner to identify their skills and they can build on them…. and teach others.

I also really connected to the point on redefining group dynamics. By giving peer feed forward, my students are learning in a collaborative environment in which everyone is committed to the improvement of all. Very cool.

Thank you for sharing this article,

Roberta

I think a lot depends on how we define ‘feedback’. Too often, feedback is just telling somehow how they did. That is a really poor definition. A much better definition of feedback is “Information that allows a system to get better at producing what the system is meant to produce.”

Imagine if we truly applied that to teaching. Suddenly, instead of asking “how’s this kid doing” we’ve have to ask “how are we doing?” The system is not the child, it’s the child, their peers, the teacher, the school system, the parents, and the community. That makes for a pretty inclusive ‘we’.

It would be a really good idea if students regularly provided feedback on the feedback so that as educators we improved our ability to help students improve.

It also forces us to ask, ‘why are we doing this?’ If the answer is just to boost SAT (or whatever the local equivalent is), then something is wrong.

I think my basic rule would be, if it ain’t feeding forward, it’s not feedback.

BTW, I stumbled across this site, but I suspect it’s going to become a regular place for me to refresh myself and feel normal. Thank you.

It is with great interest that I have just started following Cop. I came across the term ‘feedforward’ for the first time at a recent workshop. As a Visual Arts & Design teacher, it resonated with me right away and I began to make some great connections to the notion of Zone of Proximal Development(ZPD) and the value of scaffolding through formative feedback. It also connects with the pedagogy of listening and dialogue and the interactive way of learning together.

Thank you for sharing!

So glad to hear this, Hima. Thanks for sharing!

if we are shifting to feed-forward,how do we measure performance of our people? because this new perspective deals more with the development.

Many thanks

That’s a great point, and one that I work on continuously with my K-12 and corporate clients. Here are a few ways to measure performance with an eye towards development, not just appraisal:

1. Weekly check-ins: These can be used to gather real-time data, impressions and take “pulse” readings of attitude, affect and accountability.

2. “Pre-mortem:” The opposite of a postmortem – instead of reflecting on what has already passed, set goals before the start of a new term/quarter/project and develop shared understandings of what success looks like. At the end of the period, reflect together on what was achieved — and, more importantly, the conditions that led to (or interfered with) success.

Hope these two strategies help!

Joe

Feed-forward is a soft approach to constructive criticism in my opinion. I work with the ESE population and I always practice pointing out the positive before I suggest a better way of doing the task or solving the task. It seems to have positives outcomes.

I teach at small, private K-12 school where our educational model combines elements of skills based curricula, Project Based Learning, transdisciplinary studies, and a whole child philosophy. I was recently introduced to COP and have been inspired by all the relevant topics that align with my school’s philosophy.

I thoroughly enjoyed listening to/reading this blog/podcast and found it to be especially applicable to the way I try to approach teaching. Though I was unaware of the concept of feedforward up until this point, I am happy to report that I implement many components of this approach when I am coaching my students through problem-based challenges. While I agree with all six characteristics of REPAIR, I was particularly enthused with the last attribute, “it refines group dynamics”. Since I am a big proponent of collaborative learning, I love the notion of feedback being a “team sport” and the concept of creative abrasion. I am excited to start incorporating these strategies in how I approach feedback going forward. Thank you!

As an elementary teacher, I found this post to be very informative. After reading this post, I have taken a step back to consider the changes I could make to ensure my feedback turns into a moment of positive improvement for my students. My hope is to apply this approach in my classroom. Feedforward is a great way to further develop students in my class.

Thank you for this catchy take on Feedback. It highlights a number of good formative assessment points; ongoing feedback, authentic, and impactful. My favourite part was that on how to make it authentic not fluffy. You are absolutely correct, people want the truth, they just need to hear it in a particular way. By asking them to come up with solutions is brilliant and it allows them to be resilient in their learning. I feel that this form of assessment fits best within a learner based design of instruction, rather than subject driven. Could this be used as a form of assessment in a more systematic, or subject based form of instruction?

Thanks for the great read.

Feed-forward is a soft approach to constructive criticism in my opinion.

Don’t give “fluffy” feedback. You don’t have to hurt feelings, but don’t sugar-coat it either. They might read into the niceness and not get the full effect of what you’re trying to help them with.

I love this and it reminds me of working on my dissertation. It is done in pieces as part of class. Each piece will come together as a whole but along the way you get feedback and “What if’s” to guide and expand your topic. So much better than waiting until the end to get what is wrong and too late.

Love this new approach of Feedforward where teachers and students experience new ways to give and receive feedback. I believe this is a very positive way to receive feedback from others and grow and set our own goals by taking steps to achieve it based on that particular feedback. I also like how we can guide students to reflect on their own learning to have a end result that highlights their talents and interests and that later can be shared with others.

Really cool idea. Helps students (and all people) have more ownership in their growth.

“People can’t control what they can’t change, and we can’t change the past,” says Hirsch. “And that happens to be the focus of most of the feedback that we give or receive.”

truth

I believe that in order to grow you need to see what you are doing right and learn about how to make it even better. This is great! Rather than take away by giving negative feedback on what is not there one needs to teach by adding to what is already there.

I really like the idea of feedforward! It goes right along with growth mindset!

I just bought your book “The Feedback FIX” on Audiable. Can’t wait to listed to it on the way to and back from work!

Thanks so much, Laurie! Happy listening!

Great stuff!

Really like the feedforward concept

Thanks so much.

The concept is exceptional!

We’re glad you like it!

so i think i feel hesitant about using business executives management systems for students because businesses and schools have different functions in general, right? businesses have a specific goal, which is centralized for one outcome (i.e. their product). however, student learning is differentiated by its nature, or am i wrong?

i don’t even think it is wrong to gain insight from thinkers like this, but when our framework is shifted to neatly fit the carefully packaged framework of a book that i begin to pause. that kind of efficiency is not conducive to proper teaching, and so i want to stress complexity and nuance here. students learning outcomes will be different, and only in understanding that can we fully optimize their experiences.

but i want to avoid categories like that entirely too. optimization is another buzzword akin to feedforward, which is essentially just feedback with a new name. don’t get me wrong, all these deeper complexities that feedforward suggests are relevant to how we approach our feedback as teachers. but changing the name is just marketing, innovation, and other ideas akin to practices of buying and selling.

instead, i suggest that we abstract upon feedback until we reach the functional limits. we need to explore every and all avenue of feedback possible, as well as the contexts in which we give that feedback. most importantly, what is that feedback for? classroom management is important, as well as emotional health, but there are healthy ways to deal with stress and the criticism that comes with that. i think it would be a disservice to our students to pretend otherwise.

Volpe, your concerns about avoiding conflating business and educational models are heard. However, feedback from teachers is one of the most effective means of improvement. As you say, offering feedback in a variety of contexts and formats is the way to go.

Very interesting. I enjoyed every minute.

I am increasingly stoked by the blogs within COP, enough so that I am ‘regularizing’ it within my routine – thanks for these posts! I am eager to implement the feed forward approach with some college students I teach – around where they are within their learning this semester, what the expectations are, clarifying how they can meet those expectations, and setting a plan for their success – and from there, based on how it goes, perhaps sharing it out with the teachers I serve as an insutrctional coach – keep up the great work – inspiring and useful!

Jenn will be so glad to hear that you’re finding the content helpful for your practice! I think the feedforward approach could be very effective both for college students and within an instructional coaching partnership. Thanks for sharing these ideas!