Listen to my interview with Monique Morris, author of Pushout (transcript):

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

I want to tell you about Danielle. About halfway through my second year of teaching, the other teachers started talking about how Danielle Robinson was coming back. A seventh grade student, transferring over from another school. She’d start on Monday, they said. They sounded like they were talking about the weather guy predicting the worst tornado in decades.

As it turned out, Danielle was kind of legendary. She’d been at our school before, and seventh grade was more of an estimate of her grade, since she’d been absent so many times and held back at least once. Over lunch, my colleagues filled me in about her: the fights, the backtalk, the low-cut shirts, the constant truancy, the hickeys, the fights, the fights, the fights.

“Of course she’s getting sent back to us,” one of them said. “I heard she met her match at her last school and got her ass beat.”

The look on their faces, hearing this news, could only be described with one word: satisfied.

She wasn’t in my class that year, but I knew exactly who she was. You felt her coming down the hall before you saw her, because had a way of drawing a crowd. She’d shout insults and directives at the people she passed. When the bell rang, sending others scurrying to class, Danielle continued on as before, totally unaffected.

She was a force of nature, and to tell the truth, she scared me.

The following year, when I agreed to sponsor the student government, Danielle ran for student body president. The teachers had a complete fit. They scrambled, trying to figure out ways to stop her, but it was the beginning of the school year, a fresh start. She hadn’t done anything wrong yet, so they had to let her run.

She won.

Actually, there’s more to that story: The afternoon when I sat in my team room, counting votes, my mentor stopped by to see how the results were going. When I told him it was looking like Danielle would beat the other candidate, a white girl with straight A’s beloved by all the teachers, who had created a beautiful set of campaign posters, who would no doubt work incredibly hard in the position and do an excellent job, he told me this: It would be in my best interest to make sure the other girl won. I froze for a moment, not quite sure I understood his meaning. I asked for clarification, and he clarified: I should lie.

Thirty minutes later, I got on the school PA system and announced that Danielle would be our president that year.

Although I’d hoped to prove my colleague wrong, that Danielle would surprise everyone and turn out to be an outstanding student leader, that didn’t happen. I imagined myself mentoring her, developing her skills and strengths and showing everyone they were wrong about her. But I really didn’t know how. She made me nervous.

Her term as president started out okay: She attended the meetings and participated in the activities, but once the school year really kicked in, the absences started, then she got into a fight or two, and her grades were terrible. By February, according to school policy for extracurricular activities, she had to step down from her presidency.

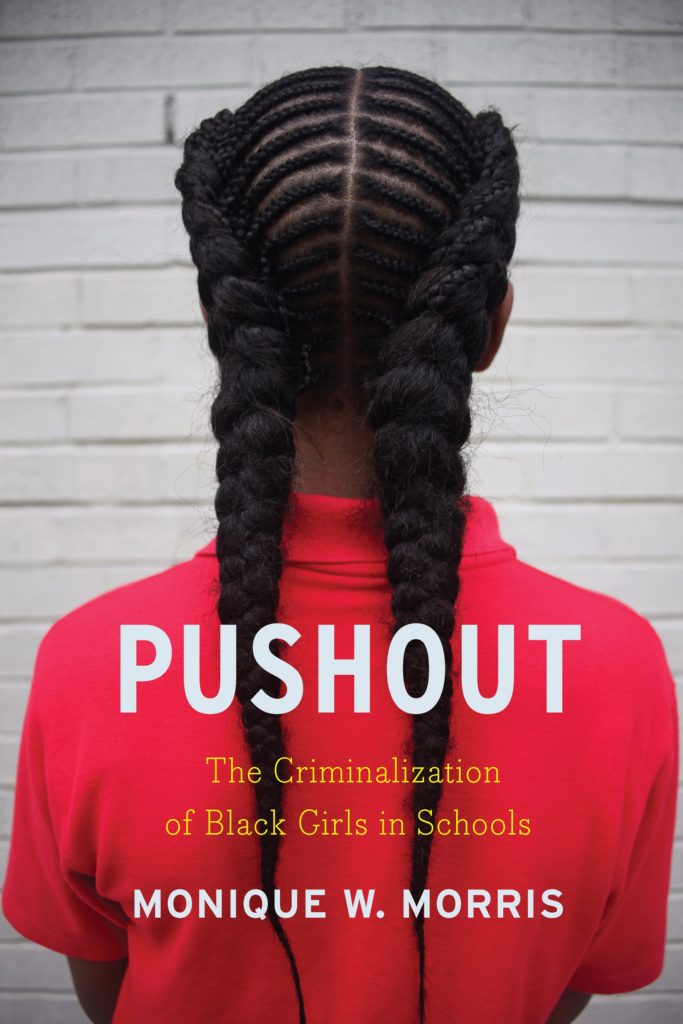

It’s my experiences with students like Danielle, my failures with the black female students in my own past, that made me take an immediate interest in the book Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools by Monique Morris, and it’s why I chose it for this year’s Cult of Pedagogy Summer Book Study. In the book, Morris examines the ways in which schools interact with black girls, the ways in which they are often criminalized when their behavior is treated as “delinquent,” and how our exclusionary responses to this behavior—usually through suspensions or expulsions—ultimately push many black girls out of school and into lives of abuse, sex trafficking, drug use, and various forms of incarceration.

For some teachers, especially white teachers, an examination of this dynamic might be overwhelming: We do our best with what we are given, some might say. If a child does not come to school ready to learn, there’s nothing we can do.

I disagree. I believe that a core responsibility of teachers is to meet each child where she is and help her grow. If a child does not come to school ready to learn, then our professional duty is to get her ready. And the only way to do that is to become very clear on exactly what each child needs. In this case, Monique Morris helps us better understand the needs of Black girls.

“Schools serve a greater social function than simply developing the rote skills of children and adolescents,” she writes. “As Black girls become adolescents, the influence of schools is critical to their socialization. This is especially important given that schools often serve as surrogates for influences that might otherwise be lacking in the lives of economically and socially marginalized children.”

If you work with students of color, and especially if your student population includes Black girls, you should consider this book to be required reading. It will deepen your understanding of what it means to truly meet the needs of these students, what mistakes you may have taken in the past, and specific steps you can take to do better. This could be especially helpful if you are not a person of color.

Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools

by Monique Morris

256 pages, The New Press, March 2016

My Personal Takeaways

Here are the points from the book that resonated most with me:

We need alternatives to exclusionary punishments.

Removing a student from class or from school through suspension or expulsion does nothing to change that student’s behavior, and because it detaches that student from the school culture and puts them further behind academically, it often makes the problem at the root of the behavior worse. Suspension is the default setting for certain infractions in so many schools, so I’m sure it’s hard to imagine what else could take its place, especially when so many schools proudly enforce zero-tolerance policies. “Zero-tolerance policies, while intended initially to keep communities safe,” Morris says in our interview, “really turned into a way for us to justify harsh hyper-punitive reactions to normal adolescent behavior.” Schools who really want to see their students’ behavior improve, rather than just removing those who misbehave, would be wise to learn more about restorative practices or programs like PBIS.

We need to build cultural competence.

We need to educate ourselves more thoroughly about our students’ backgrounds and cultures in order to more accurately interpret their behavior. By “cultural competence,” Morris is not referring to cultures from other countries. We have multiple cultures coexisting right here in the U.S., students whose home lives and cultures are quite different from what we typically expect in schools. In my interview with her, Morris describes an incident where a girl could be suspended for wearing a hat, even if she’s wearing it to cover a half-completed set of braids. “The request for her to remove the hat is actually culturally incompetent. For black girls, the two day process to braid her hair is actually less important – it was more important that she arrived at school for the test. It was more important that she was there in school to learn, than whether or not she had a hat hiding the fact that the top of her hair was not done.” If we as educators have a more thorough understanding of our students’ cultural backgrounds, we are less likely to interpret certain behaviors as defiant or problematic.

Co-construction of school rules is essential.

When teachers are the ones who define all the rules and expectations, we get less buy-in from students. One of most important ways we can improve our relationships with students is to co-construct classroom norms, to work with students to define expectations and how we will hold them accountable. In our interview, Morris explains why this works: “If educators are really focused from day one on helping their students and working with the students to co-construct what they need in the classroom to be present, and how they are going to work together around systems of accountability…when you work with kids to develop those agreements, they are more likely to be accountable to them.”

We must see ALL of our students as children.

One of the most significant shifts a teacher can make to better meet the needs of black female students is to remember that they are children. “There is this way in which we sort of cast children who are most at risk of getting in contact with the criminal and juvenile legal system as being different kinds of kids,” Morris says. “I don’t believe that. I don’t believe they are different. I believe that their experiences have been different and that has shaped their reactions to many things. They are not little women, they are children. They are developing, just like your child is developing. It’s really about leading with love.”

I have no idea where Danielle is now, but she should be in her early thirties. I pray that life has turned out well for her, but I suspect it hasn’t. I may not have contributed directly to Danielle’s pushout, but I certainly didn’t do anything to prevent it.

If I had read a book like Pushout when I was working with her, I know I would have done things differently. For one, I wouldn’t have been as intimidated. I would have seen her as a child who needed guidance and patience. I also would have tried harder: I didn’t understand the long-term consequences of her relationship with school. Most importantly, I would have asked my colleagues to read it.

And now, that’s the best thing I can do: Encourage you and the other teachers you work with to read Pushout with an open heart. I can’t wait to talk about this phenomenal book with you. In the comments below, share your own reflections on this book. Dr. Morris has agreed to join us, so if you have a question for her, include that as well. ♥

Join the Cult of Pedagogy mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to my members-only library of free downloadable resources, including my e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading!

I am currently reading Whistling Vivaldi. It outlines Claude Steele’s research at University of Michigan and Stanford on stereotypes and how they impact performance. It is a must read for every educator.

Cheryl, thanks for the recommendation!

i cannot wait to get my hands on this book. I work in s building of Danielles and it is so hard to see beyond their destructive behavior(s) to the root of it all but we must. We have no choice otherwise we will miss out on their true potential. Thank you for exposing this book to me.

Awesome! I can’t wait to read this book!

I read this book and found it to be thought provoking. In my 30+ years of teaching, I have seen this “pushout” to hold true for all girls who grow up in poverty; regardless of race or ethnicity. We must do better in mentoring and educating our girls today,so that become confident educated women of tomorrow.

I appreciate that so many educators are willing to engage in a discussion about these issues!! While school pushout is something that can affect any student, I intentionally call attention to the unique ways it impacts Black girls given their intersecting identities (and vulnerabilities) in our society –which are associated with the racial disparities we see among girls in this arena. I am confident that as educators, scholars, and community stakeholders, we can turn this around. 😉

Thank you for sharing this book! I’ve looked everywhere for it and can’t find it. How can I get a copy? Unfortunately, I teach in the school that was discussed on CNN multiple times this past school year for suspending African American students more than any other students. Our district, in late Spring, reached an agreement with the Office of Civil Rights in WA regarding this issue; our middle school (in OK)will not be suspending these kids any more unless it’s for drugs or weapons. However, we still have several being put in ISI or sat in the hall which causes them to lose instruction. This is concerning since many of them are 2 to 5 years below grade level. So. when I read your post about this book, I knew I must read it! Maybe it will give me different ways of reaching my kids! Thank you!

JC, there are several links above to the book’s Amazon order page!

Nice work! Good days 🙂 Greeting from Türkiye.

I completely agree that we need to remember that our students are children, especially those who are technically adults, having failed multiple grades. Especially those who have had to take on adult responsibilities and concerns at ages so young that their ability to learn has been negatively affected.

Somewhat tangentially, I’m curious as to what you think of the widespread application of “grit” in our schools. I get where these advocates are coming from, but, given that my experiences are limited to urban schools, I can’t imagine implying to my students that they must exude more of this characteristic. The following was a fantastic read that helped clarify my thinking on the issue, and I’d love to know what you think:

http://journalofeducationalcontroversy.blogspot.com/2016/05/the-grit-argument-continues-paul-thomas.html

I am excited to read this book. As a newish teacher I can tell this will help me in my very diverse middle school classes.

Thank for the suggestion! Will definitely read it!

As a military spouse that lives and works with all races, ethnicities, and religions, I was saddened when I got so much pushback in my classroom while teaching African American children in our last school district. As a white lady (who had my own classroom for 8 years and won a teacher of the year award from my peers) I looked ferociously for information on how to connect better. I now live in a state with very few minorities, but my heart still.burns with curiosity and need for help regarding this issue. I will definitely be reading your book. Thank you for addressing this for us.

As a military spouse that lives and works with all races, ethnicities, and religions, I was saddened when I got so much pushback in my classroom while teaching African American children in our last school district. As a white lady (who had my own classroom for 8 years and won a teacher of the year award from my peers) I looked ferociously for information on how to connect better. I now live in a state with very few minorities, but my heart still.burns with curiosity and need for help regarding this issue. I will definitely be reading your book. Thank you for addressing this for us. (I was a substitute during that time; that’s why I mentioned that I was an experienced teacher. Subs are not given much credit. 🙂

I cannot wait to begin reading and then sharing with the teachers at my school. Will keep you posted on our book study.

Thank you so much for sharing this! I teach at an HBCU and I’ve found that most of my students can relate to me (and vice versa) but I also previously worked in a group home and faced my fair share of Danielle’s. In my opinion, this is an invaluable resource not just for teachers but all fields that deal with young black girls. I feel that I can benefit from reading this and sharing it with others.

This is a bit off the subject, but I need some suggestions. My friend recently asked me for suggestions of books that have a black girl as a strong protagonist. Her daughter loves Harry Potter and asked her mother if there was a book like it that “had a black girl in it”. I was mortified to realize that I could not think of one! If anyone could help me by suggesting some, I would appreciate it. As a tie in to this article, I wonder if black girls feel little validation when there are no books featuring strong female African American characters.

Hey Jill! Check this out: http://www.teenvogue.com/story/1000-black-girl-books-drive

For some reason I am just getting to this blog post late. I am in the middle of student finals and all before Christmas Break. My hope is to purchase Pushout and share the contents with my colleagues after the vacation. Your review was quite thorough and informative. Thank you ever so much!

Thank you so much for writing this. I had many students like Danielle who other teachers wrote off, who were woefully pushed out because their teachers did not understand them. In my opinion, this likely results from a fear of blackness and racial bias against black people. Study after study about the school-to-prison pipeline demonstrates this as well as the most recent study (by Gilliam et al.) out of the Yale Child Study Center about preK students, which found that teachers tend to seek out bad behavior among black students. I look forward to reading this book, and I thank you for sharing it with us. Thank you so much for sharing the suggestions although I am not entirely in love PBIS practices. Aside from that, I love the way this made me reflect on my own experience at school–particularly in high school when I attended a predominantly white boarding school (all-girls). When I reflect on who got in trouble the most, it was black girls no matter how small the infraction. In fact, many of my white peers snuck around and did drugs and drank, and let’s just say financial and social capital–and white privilege–can go a long way. On top of being pushed out, black students, in the process of their schooling, learn that they are not enough, that they must conform to something else in other to be successful. It’s a hidden curriculum of sorts especially when little to nothing in the curricula, in the popular media, sends them, sends us, the message that we matter. In fact, I share a bit of my own experiences in my TED talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/dena_simmons_how_students_of_color_confront_impostor_syndrome

I am thankful that I was exposed to your article through a retweet. As a teacher of color, this resonated with me, as I have also taught a few Danielles – and sought to make sure that they could code switch as needed. But you also made me think about that – was/am I harder on black girls as a result? Thank you for this opportunity to reflect on my own motives.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Marian. I appreciate it.

I am appalled at educators who want to ‘rig’ the system and choose someone else the winner. Integrity starts with YOU. When we ask children to vote then we must be willing to accept the decision. It is not YOUR decision. I have always accepted who the children voted for and respected the process. ‘Pushing out’ starts right at that very moment! I am glad I never let anyone tell me who to choose.

I like to think that experience could have played a pivotal moment in Danielle’s life.💙

Thank you Monique Morris for the best reminder of all (and one that has served me well for 28 years): always remember these are children. Someone’s child that deserves the same love and respect as your own!

Great topic!

Jennifer,

I am currently a sophomore Middle School Ed major, and I’m listening to about 15 of your podcasts for my PD. This is SUCH an incredible resource for teachers. I listened to a few episodes earlier this year and bookmarked it so I would remember to come back to it. As you know, this year has been a weird one for getting field experience, so my school had to scramble to find options for us. This podcast was not one of the original options, but I got it approved and will be pushing the College of Ed to promote this resource more often.

Monique,

I am so thankful for your perspective and your willingness to speak out! I will absolutely be getting my hands on this book, and I will be checking out NBWJI and ways I can help.

Kayla,

Thank you for your kinds words! We’re so glad to know how much you’re enjoying Cult of Pedagogy resources-I’ll make sure Jenn sees this!

This was a very enjoyable podcast. I have seen the movie and have not read the book. I am inspired to do so. I agree that students should need to be included in solutions. creating the environment for their own educational experience. The impact of intersectionality is a significant issue. I think that students need to be taught how to dress – to learn what clothes, colors, make-up techniques look good on them. Right now where do you learn that? On the job? From your parents? Parents are not always a great source! I took my kids for a bra fitting and they have had a seminar from a clothing professional.

When we talk about “teachers” and addressing the behavior of students we need to keep in mind that 80% of the public school teachers are white and 51% of the students are nonwhite. I believe we are talking about race, not career function. Three-quarters of whites don’t have white friends. What impact does that have on white teachers interacting with Black and Brown students? How can you be culturally competent when your knowledge base is limited to media, and diverse-absent personal lives? The Pareto principle says that 80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes. What is the majority of that 20%? As a Black educator, why am I included in that 20% when I am also suffering the microaggressions/discriminatory practices that impact the Black and Brown students?

I see the effects of these principles play out so frequently in my student placements while majoring in education. The education system seems to operate as a mini society; time and time again, I see the ways that our school “justice system” disproportionately targets black girls for behaviors that my white students demonstrate at equal or higher rates. This is something I feel God has directly drawn my attention to during my studies. I need this book, so that I can learn more!

Riley,

Happy to hear the post resonated with you, and that you’re thinking about reading the book, too. Best of luck to you in your career.