Listen to the interview with Cara Fitzpatrick (transcript):

Sponsored by WeVideo and The Modern Classrooms Project

This page contains Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

At first glance, the notion of school choice is a no-brainer. Obviously, a parent should be allowed to choose the best school for their child. The appeal of this idea can be backed up with data — a 2023 poll asked this question:

School choice gives parents the right to use the tax dollars designated for their child’s education to send their child to the public or private school which best serves their needs. Generally speaking, would you say you support or oppose the concept of school choice?

Over 70 percent of the registered voters who responded — from both major political parties — answered that they supported school choice.

But notice the wording of the question: Generally speaking, it says. The concept of school choice, it says. That’s important. Because when it’s put that way, who could argue with it? Why would anyone say they opposed it? Every parent wants their child to have the best education they can get, right?

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Educating a group of children requires well-trained teachers, a robust collection of academic materials, expertise about differentiation and accommodations, a safe and well-equipped facility, secure technology that’s relatively up-to-date, reliable transportation, healthy food, clean water, recreational and athletic space and equipment, art and music supplies, a good clerical and administrative staff, interpreters for dozens of languages, first-aid supplies, behavior specialists, and so much more. Acquiring and maintaining all of these things takes a lot of money, management, and skill. Putting it all together, and doing that consistently year after year, is a major undertaking. It’s no wonder so many schools fall short in some way or another. The allure of school choice seems to rest heavily on the belief that in most communities, at least one school is already checking all of those boxes well, and from there it’s just a matter of parents saying, “Yes, I’d like that one please.”

But this is rarely the case. And that’s where things get complicated.

My own understanding of school choice has been heavily informed by Diane Ravitch’s 2013 book Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America’s Public Schools. In the book, Ravitch makes a case for strong, well-funded public schools, giving every student a good education, regardless of family income. She details how the school choice movement, fueled largely by for-profit interests, has systematically pulled families away from public schools with the promise of better options. Far too often, they are unable to fulfill this promise, and families are left to choose between inadequate private options and public schools that have been drained of resources.

It’s been over a decade since I read Ravitch’s book, and the question of school choice is still being tossed around. We’re heading into another big election season, so I thought it would be worth our time to unpack this topic — to look at where the movement started, how it has evolved over time, and how it could potentially impact anyone who teaches, whether it’s in a public, charter, private, or home-based school. As professionals, our opinion on this issue should be well-informed, so today we’re going to spend some time building our background knowledge.

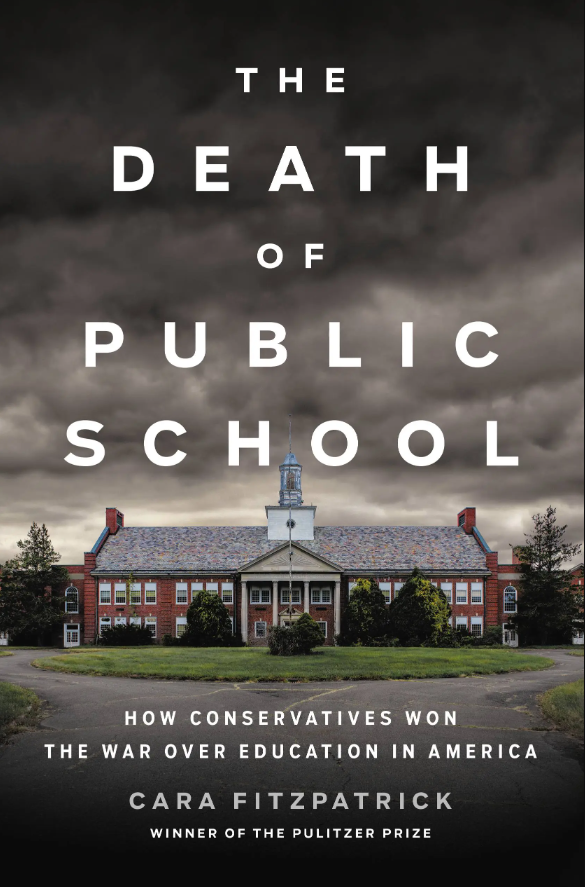

To help with that is Cara Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick has been a journalist for over two decades and now serves as Story Editor for Chalkbeat, an independent, nonprofit news organization that exclusively covers education issues. Last year, she published an extensively researched book about the school choice movement called The Death of Public School: How Conservatives Won the War Over Education in America.

When I read this book, I learned some fascinating and frankly ugly things about the history of school choice in the U.S. I was also surprised to find out that despite the title of the book, it’s not just conservatives who want school choice, and the reasons behind why some people are in favor of it are pretty varied. Despite those complications, it’s still clear that there is a well-organized movement happening right now to take down public schools, and whether you’re a public school teacher or not, this is something that should concern us all.

On the podcast, Fitzpatrick and I talk about why school choice isn’t a simple concept at all, we dig into some of the key groups that have historically pushed for it, and we explore some things concerned citizens can do to ensure that families can still get their children the best education possible. You can listen to our interview in the player above, read the highlights below, or get the full transcript here.

When people hear this concept of school choice, it really sounds harmless on the surface. Why is it not as simple as it sounds?

Fitzpatrick: School choice programs actually vary quite a lot; this idea that there’s not choice within the existing system is sort of wrong. There’s magnet schools, which are giving seats to kids outside of a zoned neighborhood school. Special admissions schools, which often have criteria like certain test scores or auditions or portfolios. Charter schools, which are intended to be a public school but they’re publicly funded but privately managed, so they are outside of the school district. And then you have an assortment of private school choice programs, which are vouchers and education savings accounts, which have become very popular now. And that basically just gives families tax dollars to pay for maybe a religious school and sometimes now even homeschooling.

So it is actually very complicated. And with that understanding, I think there’s some major issues that arise. One of the biggest ones is accountability. Financial accountability, and then also just Are these programs actually helping students? Because if we’re investing money into an educational option, we want students to do well. And so there’s this question of, well, how are they doing?

Some of them have a lot of accountability built in, where you can start to answer that question. Maybe students using a voucher, for instance, take the same standardized test as the kids in the public schools. But there’s programs where there’s very little accountability, and it’s kind of left up to the parents to decide if their children are being well served, and it’s very hard for the public to decide, you know, is this working?

And then on the accountability for the financial picture, there have been a lot of cases of fraud and misuse of tax dollars, not only with private school choice programs but with charter schools. There’s also this rise of ESAs (education savings accounts) where you could pay for online classes or tutoring or tuition. It’s very flexible. Right now you have states like Florida and Arizona where these things are quite popular where it’s not actually fraud; it’s an allowable expense to use some of that money for things like karate lessons or paddle boards or TVs. In Florida, you can actually buy Disney tickets — that’s just a really shocking use of public money that’s intended for education.

There’s definitely states where over time they have increased the amount of accountability for some of these programs because of some of those issues of fraud and misuse. It’s still just not even close to what the traditional public schools go through.

The messaging is, if you’re not happy with the public schools as a parent, you should be able to choose some other better option. But what a lot of parents may not realize is that those other options, there’s really not a way of telling, in a lot of cases, whether they are better or not.

Fitzpatrick: It would be difficult to create a system where you could really, really compare. Private schools often are serving different populations than public schools because they’re not under any legal obligation to serve, say, children with disabilities. So already it would be difficult. But at least if you had some greater level of information you could try. Because it’s very hard I think as a parent to know precisely what’s going on in a school. You know, some of it you’re taking a little bit on trust. What you do find with these programs is a somewhat high level of turnover, where a family does try something out, and then maybe midway through the year they realize this doesn’t seem to be working, or we’re not seeing the results, or this school actually can’t provide or won’t provide the same level of services that perhaps they had in the public schools. And maybe they didn’t know that going in. So you see people try something for maybe a year, and then a lot of them end up back in public schools.

The fundamental concept here is taking public money that would normally go to a public school and then funneling it to some other option, which will ultimately harm the public school; it’ll make it worse than it already is. Is that a fair assessment of the math there?

Fitzpatrick: Oftentimes the way schools are funded is based on enrollment. And so when you have students leave and try something else, the dollars often follow them. It’s not true for every private school choice program, but it is true for most. It’s certainly true for charter schools. And so if you have an existing traditional public school and you lose a class of children, probably it’s not going to close the school, but it does create a financial challenge because you’re losing some of those dollars. When you start doing that on a larger and larger scale, especially with charter schools in cities where they’re popular, they’ve started to close some of the traditional public schools because of declining enrollment. And that is one of the natural consequences of competition.

When you say that’s not the case in every place, can you help me understand that? Because I’ve always understood school choice as “this is government money that will follow the student to whatever they go to.” Are there other setups that fund school choice differently?

Fitzpatrick: Because of concerns about those types of effects on the school district, some places have put in different ways to fund it where, like I’ve seen this with charter schools where they’ve said, “Okay, if a student leaves the traditional public school for a charter school, we’re not going to take away all of the money.” So maybe the public school will retain some percentage of it, kind of to slow down the effect. And then there’s a few private school choice programs where the state has said we’re going to pay for this out of a different fund. But in most cases, it’s fair to say if a student leaves, the money follows them.

One of the biggest takeaways that I got from your book was a better understanding of all of the different groups historically that have pushed for school choice. I always had one specific idea about it, about who wanted school choice. Even the title of the book suggests that it has been largely conservatives that have wanted school choice, but when we look at the history back into the 1950s, there definitely are people who are on the conservative side of things, but then there’s a whole bunch of other groups that also wanted school choice for different reasons, sometimes opposing reasons. And there’s also kind of a dark, ugly history of school choice that I’m also not sure many people are aware of.

Fitzpatrick: What I understood at the start was that there were two sort of origin stories that I often heard from very different perspectives. I had a hard time trying to figure out how can they both be true? They’re just so different. And so I started from trying to sort that out, and really found that both stories are true — it’s almost more interesting than that. They overlap and intersect in really interesting ways.

So if you were a person who was in favor of school choice, which has tended to be driven by conservatives, those advocates for choices would talk to me about Milton Friedman — Nobel prize winning economist who had made an early proposal (in 1955) for vouchers along sort of market-driven lines. He just thought it was a better system than having what he viewed as a monopoly, which is how he viewed public education.

Before he even did that, a few years before in the lead-up to Brown (v. Board of Education) when Southern states and their lawmakers started seeing that segregation was going to end in the public schools because it was starting to be attacked successfully through the courts at the university level. They started essentially preparing to privatize the public school system. Rather than share equally in public education with Black students, these white lawmakers wanted to basically end public education in the South. And one of the tools they looked at was the school voucher. They called it tuition grants. The idea was that they would use public money to pay for white students to get a private education at an all-white private school. And it’s interesting because when Milton was writing his essay, he actually was made aware of this by his editor who tried to say, maybe you don’t want to make this proposal right now because it’s being used by segregationists. And his response was basically, you know, that’s unfortunate, it’s definitely a mark against it, but I still believe that this is a better system.

And then at the same time, there was a priest named Virgil Bloom in Milwaukee who was making a case for school vouchers or some kind of public support for private religious schools. He was arguing that religious families were being discriminated against because they would pay taxes to support public schools and then they would also have to pay tuition to a religious school to basically get their children an education that matched their values. I ultimately started the book here in the ‘50s because I thought, this is so interesting that these three arguments are being made, and that actually all of those arguments are still really relevant today.

That’s the thing that struck me right away was how much origins of school choice came down to racism and discrimination. I didn’t know this story about the lost year in Little Rock. That Little Rock schools literally just closed their public schools to all students for a year because they did not want to integrate. So no kids got a public education that year. Is that correct?

Fitzpatrick: Yeah. And Virginia did the same thing. They closed down schools in multiple cities. It was basically a massive resistance. It was saying, we’re just, we’re not going to comply with the court order, and so we’re just going to shut schools down. A lot of kids didn’t get an education. Black children of course were hit the hardest, but some white children also didn’t receive an education, and it was some of those parents who started pushing back. And it was really interesting to me because I was writing this during the pandemic when we had a period of time where schools were closed. And I think to some extent there was that similar sentiment of hey, these public schools are actually really important in a lot of ways to society.

The courts started dismantling the racist school voucher programs in the South. Right away, the federal courts in particular were saying no, you can’t do this. It’s obviously discrimination. So those programs started to go away and even as they did, there were some progressive voices that came out and started talking about school vouchers as a tool of empowerment for Black children in particular but for low-income children. And I thought, again, what an interesting overlap. Because you’re literally having programs shut down because they’re racist, because they’re excluding Black children and in the same moment, you have some progressive voices saying, hey, wait a minute. We might use that same school voucher to try to help low income Black and Latino children.

In the ‘90s, which is really when I think our modern school choice programs really took off, it’s kind of a blend of those things because it’s a lot of Black activists who are, especially in Milwaukee where they’re basically saying the public school system is segregated. It’s not providing the better outcomes we were promised via integration. It seems like this is more about shuffling kids around. That was some of the sentiment. And so it was this idea of perhaps competition would push the school system to do better for these children.

You talked about Milwaukee. Polly Williams was a big figure in that whole movement. And she was pushing real hard for vouchers for low-income families. One of the things she says, this is from page 121 in your book, she’s talking to employees of public schools that were opposed to her push for vouchers. She said, “If you all are worried about your jobs, try doing them better.” And this line of thinking, this sentiment, has been a talking point for a long time in terms of arguing for school choice. What do you think about that?

Fitzpatrick: I think when you’re talking about what we have seen now today, where we’ve opened this thing up in a lot of states to religious schools, to online schools, to even paying, in some cases, for homeschooling, then the choice that any given family might make actually might have very little to do with how the traditional public school is doing. One of the things we’ve seen with the enrollment data is that a lot of the kids that are signing up for these things were already in private schools. They’re not making a choice. They already had made it. They’re now just actually shifting the tuition cost from the family to the state. The state is now paying for this because when you say every child in the state is eligible, a lot of those kids already were in private schools, and their families were paying for that. So if you tell those families hey, we’re willing to pay for your private school tuition, I’m sure for a lot of families that’s extremely appealing. Why wouldn’t you take the state up on that?

I also think you’re not really comparing like an apples-to-apples situation. It doesn’t really have much to do with the quality of a public school if what you’re interested in is, say, a Catholic education. For your children, that has really very little to do with the public school. You’re not choosing between two things that are the same. So there’s that aspect of it.

And then I also just think so much in education is systemic, and it’s so complicated, and it’s so much more complicated than some of the slogans and talking points. I think most people who have some interaction with the public school system are aware of that. Because public schools have to serve every child. Every child that comes in has to be served, and private schools often can’t do that. A lot of families aren’t going to have the ability to homeschool or the desire to homeschool. And so sometimes what you see is places where, say, charter schools are really ascendent in the system, sometimes you see a difference between who the public schools are serving, say the percentage of students with disabilities, and who the charter schools are serving. Sometimes you see the charter schools are a little more segregated than the public schools and acknowledging that public school systems are often quite segregated to begin with. You start to see this kind of thing that’s less about really are these people over here in the public school doing their jobs and more about all of these other factors.

My sister is a special ed teacher. My mom’s a retired special ed teacher. And some of the things that teachers in those classes are dealing with and doing are so complicated and so difficult. Some of those students are not going to be well served outside of the public schools. Those private schools don’t have the services for them. And so I just think it’s really hard to compare what maybe is going on at, say, like my sister’s school versus the private school down the road that doesn’t even have the ability to offer those services.

It sounds like after all of this research, you don’t really think that the school choice movement is as big of a threat to the health of public schools that it’s made out to be sometimes.

Fitzpatrick: A lot of times school choice people will say we’ve had school choice for a very long time, and the sky hasn’t fallen on public education. And in fact, there’s some research showing that public schools do improve in various ways via competition.

But one thing I think is concerning right now is that you’ve seen this really notable shift in the way that school choice advocates are trying to pass programs. It used to be that they talked a lot about civil rights, that school choice is a civil rights issue. They talked a lot about empowering low-income children, empowering Black and brown children. And now it’s this really aggressive attack on public education, these accusations about teachers indoctrinating students and what are the schools really teaching your kids, this insinuation that bad things are occurring in public schools. And that’s been a really notable change in the way people are talking about it. And it’s not even a subtle one. It’s not like a conspiracy theory. Places like the Heritage Foundation have literally published papers saying, you know, we should use culture war issues to win legislatively on choice, that we should attack public education.

You could debate whether or not that’s been successful or whether or not that’s a good strategy. I mean it’s not really my role to debate whether that’s a good way to go. But I do think it’s fair to say that it’s concerning because most American kids are still going to public schools and what’s the end game there if we’re trying to discredit public education? What purpose does that serve? I mean it might pass some school choice programs. It might steer some people out of public schools, but what is kind of the larger consequence of that? There’s not enough conversation about what the common purpose of public education is meant to be. If public education is supposed to be that there’s this common system where the children of the country learn our shared history and our shared values and some of these larger purposes of public schools, what are we getting when we tear that down?

If somebody is concerned about this issue, what are some things people can do with this information to make this situation not go way off track?

Fitzpatrick: You can advocate for tighter controls and stricter accountability. There’s really nothing to say that you can’t have a school voucher program where the kids take the same test, and you get at least some data about how children are doing. There’s nothing to say that you couldn’t have those programs and have background checks or requirements about what teachers who teach in those programs, the education that they have, the certifications that they have. You can attach a lot of those same things to these programs that are attached to public schools.

And then for public schools, if you’re a parent, I think one of the best ways to advocate for public education is to actually use public education. I hear from people who will tell me, I really wanted to send my child to the public school, but the class sizes are large or the art program’s been cut or they don’t have band. But it’s sort of like a self-fulfilling prophecy — the public school is not going to be able to pay for band or art if everyone leaves it. There has to be some level of engagement with that. Of saying, well, it doesn’t have art, but it does have these other things that are important to me. And we have with public education a built-in democratic process where you can go to school board meetings and you can be involved.

Cara Fitzpatrick’s work can be found on Chalkbeat. The Death of Public School is available on Bookshop.org.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Hi, I enjoyed episode 228 on school choice, I am a charger school teacher and I drove my kids 45 minutes every day to get my kids a classical education, a kid of education the local public school would never provide.

I would love to hear you interview the great Thomas Sowell. Mr. Sowell wrote the book Charger Schools and Their Enemies. I think you will find it interesting.

Thanks for what you do,

Sincerely,

Jacqui Lenhardt

Thanks for producing this particular show!

One anecdote I share that surprises those I’ve spoken to who may not be ed policy-ish geeks like me (which you cover in the podcast):

Private schools aren’t obligated to take your child – especially those w special needs – and in fact many obligate you to sign a waiver if your child has a learning or physical disability.

When I was a principal, sometimes parents would request to meet with me and some of the educational leaders (teacher, school psychologist, special education teacher, to name a few) to review what our public school does provide, and what the private school they were considering doesn’t provide, when it came to special education services like occupational therapy, or adaptive physical education, or speech pathology services, or learning center special education services. They showed me the enrollment form which had the waiver/disclosure language something to the effect: “As a private school, we are not bound to the Individual with Disabilities Education Act, and therefore do not provide special education services.”

This isn’t a knock on private schools – there there and provide options to parents. But please public, don’t compare the results of public schools vs private schools, especially on test scores, when they don’t serve the same students, and aren’t designed to serve the same students, and don’t have the same regulatory oversight and legal protections for students and families.

Both my mother and my wife teach at public schools. I’m a huge advocate of public schools. I’m a product of public schools. But I think school choice is still the right idea.

I listened to this episode with a lot of hope. The challenges of public schools are pretty well known. They require a large amount of capital investment. Education is often the first or second highest expenditure in any county. But I think we also all know that spending more money doesn’t necessarily get us a better product. Public schools. standardize practices so they can replicate results. It’s often a factory mentality because of the volume of education that has to be distributed.

This isn’t my podcast. However, I wish there was a point counterpoint argument here. Thoughtful people think differently on this issue. Thoughtful people can likewise be conservatives or liberals. Conservatives are not the enemy nor are liberals. I sincerely worry when critical thinking gets waylaid by ideological prescription.

Hi Kenny,

Thank you for taking the time to share these thoughts. It took me quite a while to narrow down our conversational focus to something we could do in about an hour; there was so much in Cara’s book that was worth digging into and I’m sure we missed some nuance. With that said, I concede that her book and our conversation stacked more evidence against school choice, although I think I was clear at the outset that I have no problem with school choice as an idea. It’s the way it’s been executed, and some of its origin story, that is concerning.

Yes, most public schools absolutely operate on a factory model, and there are a lot of conversations happening about why that’s a problem. I’m so encouraged by all the people working to change that, and I’ve featured some of them here, like the teachers at the Apollo School, Stephen Ritz’s Green Bronx Machine, and the work being done by schools using the Modern Classrooms Project’s self-paced, mastery-based approach. All of these are happening inside regular public schools. If we continue to put energy into these kinds of programs, and get more involved in making our own local schools places where this kind of learning happens, then all children in our communities get the benefit of an outstanding education, rather than just a select (or lucky) few.

What has happened in recent years, which Cara mentioned in our conversation, is that a segment of conservatives have openly mounted a more direct attack on public school — a search for Christopher Rufo will turn up pages of articles on that. This is a different animal from just being in favor of choice, and it threatens to move us even further from the ideal I just described above.

The comment section of every one of my posts is an opportunity to continue the conversation that was started in the post, and as long as people keep things respectful and offer some value to my readers, I’m open to all ideas here. I would invite you to add more comments here that would give us the point/counterpoint you hoped to hear in the episode.

Wonderful point-counterpoint here. Smart, thoughtful, generous comments back and forth. I’ll follow your podcast more.

I came to this podcast episode without prior engagement with Cult of Pedagogy because I am trying to learn more about school choice and whether it can complement great public schools. I am a former public school teacher with a big heart for public schools but also Catholic schools. As I’ve gotten to know more about Christian (non-Catholic) schools recently due to life circumstances, I am concerned by the seeming battle between school choice and public school advocacy. I understand there is only so much funding that can go around and not everything can be a priority, but I am eager to keep coming back to Cult of Pedagogy for nuanced inquiry about public education and school choice supporting one another (if that’s possible, or even a legitimate way of thinking about this issue).

Thank you for this, Alexander.

Most of what I cover here has more to do with instructional approaches, and I usually stay away from policy unless an issue has become so big I think teachers would appreciate that I look at it more closely. With that said, I do like to shine a light on programs that are doing things well — you’ll find most of these under the programs & systems tag: https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/tag/programs-systems/

I just listened to this for the 2nd time. I think this is very important and iI empathize with both sides, though I feel strongly that public schools are linked to democratic principles of all kinds. Re: Disneyland tickets purchased with school vouchers, could be that families are struggling and have low expectations of meaningful change, so just want to have a fun day at the expense of the government that isn’t 7giving them much else for their tax dollars right now. But important to fix the system! I live overseas and was surprised to learn that in most countries, school funding isnt tied to household incomebin the district. I think thats the root of inequalities in US schools.

In Detroit, school of choice does sometimes mean students moving to charter schools, but it also largely means people moving to other neighborhood public schools. So people live in one neighborhood, then send their kids to a school a few miles away that is supposed to be a “better school”. It is usually a more white school, a school in a slightly more affluent neighborhood. It has resulted in integration that hadn’t happened before in the close suburbs of Detroit. However, some of the teachers who have been at those schools for twenty years often operate from white supremacy without even necessarily knowing it, are sure the school was better back in the day, view the students as not belonging, and complain about the lack of connection between students families and the school.

This still happens in cities around the country. Thank you for pointing it out.